Brilliant Classics

1405 products

-

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsPizzetti & Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Arioso / Panzarella, Cicchese

Any cellist seeking new repertoire, and any listener in search of Romantic cello sonatas beyond Brahms, will alight upon this album with...

February 07, 2020$13.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsVan Veen: Piano Music, Vol. 2 / Audience, Flute Octet Blow Up

Jeroen van Veen has won international success with albums of Satie, Part, Glass and Riley. These are only some of the most...

July 27, 2018$56.99$28.48 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant ClassicsMozart Contemporaries: 18th Century Music For Bassoon / Carmen Mainer Martin

The starting-point for this unique recital is a true Mozart rarity, the Sonata for bassoon and cello K292 which Mozart wrote in...

$13.99February 12, 2021 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsMercadante: Chamber Music For Flute / Gian-Luca Petrucci

At the time of his death in 1870, Saverio Mercadante was known as a director and administrator first and foremost, who had...

October 16, 2020$13.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant ClassicsLocatelli: Complete Edition

a MusicWeb International Recording of the Month! Pietro Antonio Locatelli is known first and foremost as the composer of twelve virtuosic violin...

$77.99October 30, 2015 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsLe Plaintif / Cordevento

An ‘illuminating’ series (Fanfare) reaches Volume 9, presenting the complete piano sonatas on instruments of the period. The French grand siècle is...

January 22, 2021$13.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsKuhlau: Complete Sonatas for Flute and Piano / Tozzetti, Caturelli

Friedrich Kuhlau (1786 - 1832) lived and worked during a transitional period of classical music. A contemporary of Beethoven and Schubert, his...

August 27, 2021$17.99$8.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

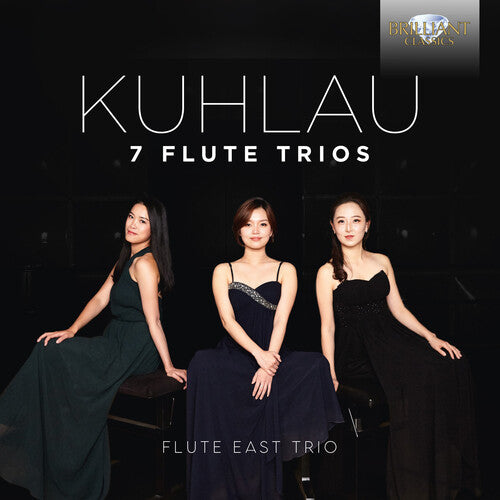

Brilliant ClassicsKuhlau: 7 Flute Trios / Flute East Trio

Born in Hamburg in 1786, the son of a military bandsman, Friedrich Kuhlau showed early musical promise and took lessons with a...

$17.99January 01, 2021 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsJeroen van Veen: 24 Minimal Preludes

Over the course of musical history, the Prelude developed from a short, semi-improvised introduction to a larger scale work into a work...

August 26, 2016$21.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsGeraldine Mucha: Chamber Music / Stamic Quartet, Prague Wind Quintet

Geraldine Mucha learned to read music before words; her Scottish father, Marcus Thomson, taught at the Royal Academy of Music. Having turned...

January 22, 2021$13.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant ClassicsGaluppi: Piano Sonatas / Damiano

At a time when only Bach and Scarlatti were Baroque-era composers in the repertoire of pianists rather than harpsichordists, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli...

$13.99September 10, 2021 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant ClassicsEscher: Orchestral, Chamber & Choral Music

Rudolf Escher (1912-1980) is without doubt one of the most original, intriguing and successful Dutch composers of the 20th century. In his...

$21.99May 01, 2020 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsEasy Studies for Guitar, Vol. 2/ Porqueddu

This second volume in the 3-part series of Easy Studies for Guitar continues to focus on lesser-known modern compositions that lend themselves...

January 26, 2018$21.99$10.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Brilliant ClassicsDialogo d'Amore: Frottolas for Isabella d'Este / Falcone, L'Amorosa Caccia

The Italian frottola is an important predecessor to the madrigal and is a secular piece made up of three to four voices...

$13.99March 06, 2020 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleBrilliant ClassicsDebussy, Ravel & Franck: French Violin Sonatas / Barati, Wurtz

Among the most talented violinists of his generation, Kristóf Baráti has made a string of recordings for Brilliant Classics that have been...

February 07, 2020$13.99$10.99

Pizzetti & Castelnuovo-Tedesco: Arioso / Panzarella, Cicchese

Any cellist seeking new repertoire, and any listener in search of Romantic cello sonatas beyond Brahms, will alight upon this album with enthusiasm. Although Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968) studied under Ildebrando Pizzetti (1880-1968) at the Conservatoire in Florence during the early years of the 20th century, their paths diverged when the Jewish Castelnuovo-Tedesco had to emigrate to the US in 1938. Back in 1921 Pizzetti had composed a Cello Sonata thematically unified across its three movements, with an ‘agitated and anguished’ Scherzo at its heart, while the slow outer movements translate elements of medieval chant and polyphony into soulful meditations. Three years later he composed a cycle of Tre Canti – three songs more commonly encountered in the version for violin and piano but better suited to the pitch and expressive range of the cello, so closely molded to that of the human voice. And these really are ‘songs without words’ – by turns affectionate, tender and impassioned. The younger Castelnuovo-Tedesco was more concerned to establish a mood than to tell a story in his instrumental music, and the first movement of his Cello Sonata from 1928 is an object example of his tendency to face both backwards and forwards, artistically speaking, so that he can evoke Romanticism while simultaneously casting doubt upon its certainties and view them from an anxious distance. The album is rounded off with the delicious fantasy on the Largo al factotum and ‘Un voce po’ fa’ from Il barbiere di Siviglia which Castelnuovo-Tedesco composed in two versions, for Jascha Heifetz and Gregor Piatigorsky, having emigrated and become a fixture on the Hollywood musical scene.

Van Veen: Piano Music, Vol. 2 / Audience, Flute Octet Blow Up

Jeroen van Veen has won international success with albums of Satie, Part, Glass and Riley. These are only some of the most significant composers whose work he has recorded for Brilliant Classics in building a library on record of minimalist piano music. Simplicity, repetition and appealing melody are the qualities shared by all the composers who subscribe to this aesthetic, and they underlie van Veen’s own compositions. Although subtitled Volume 2, this is the third album to focus exclusively on the pianist as composer. Books 1 and 2 of his Minimal Piano Preludes were reissued in 2016, and won high praise from MusicWeb International. Further preludes feature in a release of his piano music, and this sequel takes us up to Minimal Prelude No.60, a ‘tango for organ’. “All my music is about time and space,” says van Veen. “The duration of music is an essential part of the concept in my music. The concept of music, specifically my minimal oriented music, only can exist in time. The slow progression, building of the material, the motifs and the search for new sounds is audible in this [album].” All the works featured here were composed between 2010 and 2018. Continuum is a concertante work for piano and flute octet. Incanto is another album-length piece, entirely composed in an unusual 11/8 time signature. Ripalmania is written for six pianos, a scoring which creates an entrancing effect. In Velvet Piano van Veen explores the timbral possibilities of pianos prepared with objects after the style of John Cage, though without the American composer’s aim of disconcerting the listener. The final portion of the release is a celebration of minimalist jazz, in which the border between composition and improvisation almost vanishes.

Mozart Contemporaries: 18th Century Music For Bassoon / Carmen Mainer Martin

The starting-point for this unique recital is a true Mozart rarity, the Sonata for bassoon and cello K292 which Mozart wrote in 1775, pairing the bass members of string and wind families not to comic effect but rather demonstrating their expressive versatility and contrasting tone-colors, in the hands of sufficiently practiced performers; the Sonata is accessible by only the most skilled amateur performers such as its original dedicatee, the nobleman, pianist and occasional bassoonist Thaddaus Wolfgang von Dürnitz. The count’s considerable musical gifts may be judged from the teenaged Mozart’s dedication of the Piano Sonata K284 in the same year: one of the composer’s first works of absolute genius, notably in the extraordinary landscape of its long theme-and-variation finale. The bassoon-and-cello sonata may not rival K284 for lightly worn profundity, but in its Andante we may still hear the teenaged composer attaining an idiom of sublime gravity which anticipates masterpieces such as the Sinfonia Concertante K364. Rarer still on album is the creative output of Dürnitz himself, represented here by four sonatas for bassoon and keyboard from a collection of six. He evidently cultivated a particular facility at the top of the intrument’s range, notably in the elegiac introduction to Sonata No.3. Dürnitz was no dilettante musician, to judge from his ready assimilation of Classical-era convention and the kind of virtuoso writing in the quick movements that challenges conceptions of the bassoon as a sturdy accompaniment to more agile musical companions. Between these two composers in the register of fame falls the French composer Francois Devienne, four years younger than Mozart and author of six Duos Concertants Op.3 for two bassoons in around 1782; Carmen Mainer Martin presents two of them here, with the second part arranged for cello in the same disposition as Mozart’s sonata.

Mercadante: Chamber Music For Flute / Gian-Luca Petrucci

At the time of his death in 1870, Saverio Mercadante was known as a director and administrator first and foremost, who had steered opera houses and then conservatoires through choppy waters at an especially eventful time in Italian political history, rising to become the dominant figure in the musical culture of mid-19th century Naples. Secondly, he was acknowledged as an opera composer of distinction and fluency, if not ranked on the level of lyric geniuses such as Rossini and Bellini. A stroke in 1862 left Mercadante blind, and he began to concentrate his remaining energies on the field of instrumental music which had launched his career in the 1810s. Almost immediately after his death, however, Mercadante’s name became obscured, and only in the last couple of decades have his operas and other works been revived outside his native Italy. Most of the works on this album were composed at either end of his long career, but they are unified by the vocal style of writing for his chosen solo instrument. Perhaps because he valued it as a soprano without words, so to speak, Mercadante wrote much for the flute – concertos, trios, quartets and more – and it takes on the character of a bel canto heroine in his hands, exploiting the resources of the most accomplished performers with coloratura agility and elegant phrasing. Gian-Luca Petrucci’s choice of repertoire opens with a work specifically indebted to the lyric stage, a set of variations composed in 1759 and based on ‘La ci darem la mano’ from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. He continues with two more attractive variation sets and then a striking scena for piano, cello and voice, Il sogno, to a text by Guacci, with the obbligato cello part transcribed here for flute.

Locatelli: Complete Edition

Pietro Antonio Locatelli is known first and foremost as the composer of twelve virtuosic violin concertos which were published as his opus 3 in 1733. In this capacity he is considered the "founding-father of modern instrumental virtuosity" as the Dutch musicologist Albert Dunning writes in New Grove.

Locatelli was a child prodigy and became a member of the instrumental ensemble of the basilica in his birthplace, Bergamo, at the age of 14. In 1711 he went to Rome, where he came under the influence of Corelli, although there is no evidence that he was his pupil. He spent most of his lifetime in Amsterdam. In all probability this was mainly because the city was the centre of music publishing in Europe. His opus 1 was published by Le Cène, who also printed other collections of orchestral music. Locatelli took care of printing and selling his own chamber music, though, which resulted in the publication of seven collections, from the op. 2 to the op. 8. As at his death he turned out to be quite prosperous he must have been a pretty good entrepreneur. He also sold musical instruments and strings, and collected books and art. Although he mostly kept his distance from social life in the city he regularly gave concerts at his home, probably for a circle of wealthy citizens.

Locatelli was arguably the greatest virtuoso of his time, and he himself certainly thought so. The story goes that after performing a dazzling solo he exclaimed: "Ah! What do you have to say about that?" However, if it comes down to style and taste, opinions were sharply divided. The Dutch organist Jacob Wilhelm Lustig, while acknowledging Locatelli's ability to captivate his audience with his virtuosity, stated that his playing was "so brutal that sensitive ears found it unbearable". There is a report about a concert by Locatelli and his French colleague Jean-Marie Leclair. It says that Leclair played like an angel and Locatelli like the Devil. Although there is considerable doubt about whether this concert ever took place, the comment sheds some light on the controversial nature of Locatelli as a performer. The same is true of his compositions. The English journalist Charles Burney showed little enthusiasm for his music which "excites more surprise than pleasure". His contemporary Charles Avison, a staunch admirer of Locatelli's colleague Francesco Geminiani, characterised Locatelli's music as "defective in various harmony and true invention". There are some pretty harsh judgements in modern times as well; the article on Locatelli in the 1954 edition of the English music encyclopedia Grove states: "He oversteps all reasonable limits and aims at effects which, being adverse to the very nature of the violin, are neither beautiful nor musical, but ludicrous and absurd."

The unease about Locatelli's style of playing in his own time may also have been the fruit of the changes in musical taste during the 1730s and beyond. There was a longing for a more 'natural' style, away from pyrotechnics for their own sake. It was the time when Nature was seen as the source of Truth, and the closer a man got to Nature, the closer he got to the Truth. The specimens of these ideals were Christoph Willibald von Gluck in opera and Giuseppe Tartini in the field of instrumental music, and particularly the playing of and composing for the violin. Today the scepticism about his output has not disappeared which could explain why it is not regularly performed and recorded, certainly not in comparison with the likes of Vivaldi and Geminiani. That makes the complete recording of his oeuvre which is here released by Brilliant Classics particularly welcome. It gives anyone who is interested in 18th-century violin music the chance to judge for himself if there is any truth in the assessments which I have quoted above.

Let us turn first to the violin concertos which are the part of his oeuvre which is probably most controversial. Locatelli published them as his op. 3 under the title L'Arte del violino, comprising twelve concertos for violin, strings and bc. He added 24 capriccios for violin solo, one for every fast movement, as a kind of cadenza. In those days music was printed for performing musicians, and only in parts - scores did not exist. Question is how many violinists of those days were able to play the solo parts. The solos in the concertos as such are already difficult enough, although probably within the grasp of the best violinists of the time. The capriccios in particular are extremely difficult. If these concertos were played elsewhere it is possible that the capriccios were omitted. After all, they were added with the indication ad libitum. However, the publication may have been intended as a demonstration of Locatelli's own playing technique in the first place. These capriccios clearly inspired Nicolò Paganini in the composition of his Capriccios op. 1. In the booklet to a recent disc Locatelli's Capriccio No. 7 and Paganini's Capriccio No.1 were both printed and they show a remarkable similarity.

Having listened to these concertos I have come to the conclusion that the negative assessments don't do them full justice. There is plenty to enjoy, and the slow movements are not devoid of expression. It is probably the capriccios which are the most problematic. It is certainly compelling to hear these escapades on the violin and it is surprising how Locatelli explores the instrument's possibilities. Their musical quality is variable: the capriccio played in the closing movement of the Concerto No. 3 in F, for instance, is musically rewarding. As for the Concerto No. 11 in A and its capriccios where Locatelli explores the highest positions of the violin, up to the 19th, these are a demonstration of technical prowess rather than substantial musical statements. It is partly down to the performance whether the musical qualities of these concertos and the capriccios come across. Ruhadze produces a beautiful tone, and even in the most difficult passages there is no hint of stress. It is one of the virtues of these performances that they go beyond mere technical exhibition. Ruhadze and his colleagues underline the musical substance of these concertos in a convincing manner.

Among Locatelli's chamber music the Sonatas for violin and bc op. 6 are most close to the violin concertos. These sonatas certainly reflect the composer's own technical skills. Improvisation is also an important element here. Several sonatas include extended cadenzas, often over a pedal point in the bass. The last sonata even ends with a capriccio, called Capriccio Prova dall'Intonazione, in which the violin is unaccompanied until the final cadenza. Here Locatelli moves away from the traditional pattern as it had been established by Corelli. Most sonatas are in three movements and open with an andante which is followed by two fast movements. The closing movements are mostly in the form of an aria with variations. Two sonatas are in four movements, but again Locatelli follows his own path: the Sonata VII in f minor, for instance, opens with a largo which is followed by a grave, a vivace and the common aria with the indication cantabile. Virtuosity is the name of the game here, and in this respect these sonatas are impressive. The sequences of variations in particular are used to explore the capabilities of the player and his instrument; in some variations the violin moves to the highest positions. In regard to expression the listener is probably less well served. If I want to hear expressive violin sonatas I probably won't turn to Locatelli's op. 6. That is not the fault of the performers. Once again Igor Ruhadze delivers impressive interpretations in which he fully explores the features of these sonatas.

As trio sonatas were intended for amateurs they are usually far less demanding. That is certainly the case with Locatelli's trio sonatas. The op. 8 is remarkable in that Locatelli here brings the two genres together in one collection. It comprises ten sonatas which in itself was highly unusual: almost every collection included either six or twelve pieces. It seems likely that op. 8 is a collection of left-overs and consists of pieces he had not yet published. The inclusion of trio sonatas made this opus suitable for amateurs and because of that the solo sonatas could not be too complicated. They include several features which we also met in the op. 6 sonatas but virtuosity is not as prominent as in the other collection. The most brilliant sonata is No. 6 which is the last solo piece. Some of these sonatas follow the pattern of the Corellian sonata. The four remaining pieces are trio sonatas, and here Locatelli comes up with a surprise: the last one is not for two violins but for violin and cello. It is probably the result of a commission from an amateur cellist or Locatelli may have written it on his own initiative for some rich citizen in Amsterdam.

The op. 2 and op. 5 are entirely devoted to trio sonatas. The latter comprises six sonatas for either violins or transverse flutes. That in itself explains why they are not overly virtuosic from the angle of violin technique. Obviously something like double-stopping was out of the question. Stylistically they are closer to the ideals of those who advocated a more 'natural' style. Again the number and order of the movements is various. The Sonata VI in G is different in that it comprises five movements. The latter is the most 'baroque' in that it is entirely structured as a canon. The ensemble is split into two 'choirs', each with one violin and basso continuo. This example of strict counterpoint is quite unique in Locatelli's oeuvre. Some movements in this set include daring harmonies, for instance the closing vivace of the Sonata IV in C and the Pastorale which closes the Sonata V in d minor. The latter is arguably the most 'modern' of the set, with the violins playing largely in parallel motion in the second movement (vivace).

These sonatas are included here in two different performances, reflecting the alternative scorings indicated by Locatelli. Musica ad Rhenum doesn't adhere strictly to the suggested scoring of two flutes; in some cases flute and violin share the melody parts. Those who know other recordings by this ensemble will not be surprised about the treatment of the tempi. There are many moments where the ensemble slows down in order to enhance the tension and improvisatory elements are a fixed part of Musica ad Rhenum's interpretations. I am all in favour of this but sometimes they go a little too far. The largo from the Sonata III in E ends with a ridiculously long appoggiatura.

The same features are noticeable in the ensemble's recording of the twelve Sonatas op. 2 for transverse flute and bc. It may come as a surprise that Locatelli composed and published a set of sonatas specifically intended for the transverse flute. However, the inventory of goods compiled at his death included three flutes. He even taught the flute to an amateur from Amsterdam, Mr. Romswinkel. Moreover, it has been observed that several sonatas have also been found in versions for violin. In those cases the flute sonatas may be later adaptations, and this could explain the violinistic features in some of them. The layout is varied here as well: five of the sonatas are in three movements, the others in four. The last sonata is like the closing work from the op. 5: it is in a strict canon; only here the basso continuo is not split. The fact that a number of copies of this set have been found across Europe attests to its popularity.

Musica ad Rhenum treats these sonatas with considerable freedom. In the liner-notes to the first release of this recording - unfortunately not included here - Jed Wentz discusses some aspects of performance practice. Among them is the freedom of the cellist to move away from the line as written down by the composer. A specimen of that can be heard in the last movement from the Sonata I. In the largo which opens the Sonata II Wentz seems to play a kind of cadenza which is rather unusual in a sonata. This kind of thing results in these performances being theatrical and full of surprises. However, I find it hard to believe that it was the intention of a composer like Locatelli that the performer should improvise a solo - without basso continuo - lasting over three minutes as Wentz does here in the first allegro from the Sonata VI. Another issue is that of consistency: why do we get such a long solo in that movement and not in other ones?

At the end of this review we turn to the orchestral music, in this case the genre of the concerto grosso. This was one of the most common genres of instrumental music and here again - as in the case of the trio sonatas - it was Arcangelo Corelli who had established the model. The orchestra was made up of strings and bc and divided into a concertino of two violins and cello and a ripieno, comprising the other instruments. Obviously the size of the whole ensemble could differ from one occasion to the next. From Corelli's concerti grossi we know that they could be performed by a large group of up to forty instruments and with a mixture of strings and wind but also with the smallest formation of two violins, cello and bc, turning them into trio sonatas. That is the reason the term 'orchestral music' is not the most appropriate here. Locatelli's Concerti grossi op. 1 were published in 1721 and strongly adhere to the tradition established by Corelli. The set comprises twelve concertos: eight da chiesa and four da camera. The Concerto No. 8 is - as in Corelli's op. 6 - a Christmas concerto which ends with a Pastorale. That is about the only part which is reminiscent of Corelli's Christmas concerto or Christmas music in general. The other movements are quite different. Locatelli follows his own path in that he extends the concertino from three to four by including a viola part. In two of the concerti grossi he even adds a second viola part. There are also some solo passages for the first violin and these have some virtuosic traits but certainly not of the kind we meet in the violin concertos or the sonatas op. 6.

In 1735 Locatelli published his op. 4, a collection of six concerti grossi and six so-called Introduttioni teatrali. This set shows a greater variety in structure: the introduttioni teatrali are all in three movements, fast - slow - fast, just like the Italian opera overture. It is not known whether they were written as such, for instance for performance in the Amsterdam city theatre. The concertino is again for two violins, viola and cello. That is also the case in the concerti grossi; here the number of movements varies from three to five. The violin parts are more virtuosic than in the op. 1 or the introduttioni. The most remarkable is the No. 8 which has the addition a imitazione de' corni da caccia. In the first three movements the concertino plays in unison with the corresponding ripieno parts, but in the last two movements the first violin has a solo role and at this point we hear some of the virtuosity of the solo concertos; that includes double-stopping suggesting two horns as the title indicates. The set closes with a concerto with four obbligato violin parts, a form which was practised in Rome in the early decades of the 18th century.

Lastly, in 1741 the six concerti grossi op. 7 were published, not by Locatelli himself, but by Adriaen van der Hoeven in Leyden. The number of movements varies from three to five. The concertino is usually made up of two violins, viola and cello; one concerto omits the viola. The last concerto is the most unusual and - because of that - the one which is most frequently performed. It is a kind of instrumental opera, called Il pianto d'Arianna. The fate of this mythological figure who is left by her lover Theseus was the subject of many cantatas and operas in the baroque era. The turmoil of Ariadne's emotions is vividly depicted with purely instrumental means. One wonders what an opera from Locatelli's pen - had he written one - would have been like.

The theatrical character of this work is well conveyed. It is one of the few concertos from Locatelli's pen which is available in various recordings. For the rest of his concerti grossi only a few alternatives are available. Here I would especially recommend the Freiburger Barockorchester which recorded some of the op. 1 and the Introduttioni teatrali from the op. 4. I probably prefer these, but that is rather a matter of taste and doesn't imply that the performances by Igor Ruhadze and his Ensemble Violini Capricciosi are inferior. I have certainly enjoyed their performances as much as Stuart Sillitoe.

If you are interested in Locatelli and want to have more than just excerpts from his oeuvre this is a set not to be missed. Overall this is a major achievement and the first attempt to do this composer real justice. He has more to offer than virtuosic violin concertos. In some cases one may ask what is the point of releasing large boxes with so many discs — which is a speciality of Brilliant Classics — but in this case I have no doubt that this is an important addition to the discography.

– MusicWeb International (Johan van Veen)

Le Plaintif / Cordevento

An ‘illuminating’ series (Fanfare) reaches Volume 9, presenting the complete piano sonatas on instruments of the period. The French grand siècle is most often viewed through the gilt-framed mirrors of Versailles, showing the pomp and splendour, the feasts and formality of Louis XIV’s reign. However, the composers of his court took special pains to represent and analyze the human condition in all its moods, not least mourning and sadness. The entire aesthetic imaginary of this era is imbued with the power and charm of tears: the audience – in the words of philosopher Bernard de Fontenelle – wants ‘to be moved, agitated, [...] to shed tears. The pleasure one takes in crying is so curious that I cannot help but think about it.’ The aesthetic of sorrow and grief was so powerful that not even instrumental music could resist its charm. Marais, Hotteterre and their contemporaries wrote eloquent examples of the plainte and the tombeau as well as courantes and allemandes which conveyed a sad and lamenting mood, through slow tempos, minor modes dissonance and chromaticism. It is from this eloquent repertoire that Cordevento, expanded for the occasion to a five-person lineup, has assembled an imaginative programme. The lion’s share is drawn from two collections of suites en trio by Marin Marais and Antoine Dornel, performed by Erik Bosgraaf (recorder) and Robert Smith (treble viola da gamba) with their colleagues Izhar Elias, Israel Golani and Alessandro Pianu (respectively on baroque guitar, theorbo, harpsichord) providing attentive and generous continuo accompaniment. Erik Bosgraaf also takes the spotlight with a selection of pieces for solo recorder and basso continuo by Hotteterre, Philidor and Montéclair, while his Cordevento co-founders Izhar Elias and Alessandro Pianu contribute solo pieces by Campion and d’Anglebert.

REVIEW:

The aesthetics of grief and mourning have had a great influence on the instrumental music of Marin Marais, Pierre Philidor, and Jacques Hotteterre. This is expressed on the CD Le Plaintif, on which the Ensemble Cordevento has put together a program in which the recorders of Erik Bosgraaf in particular achieve special expressiveness.

– Pizzicato

Kuhlau: Complete Sonatas for Flute and Piano / Tozzetti, Caturelli

| Friedrich Kuhlau (1786 - 1832) lived and worked during a transitional period of classical music. A contemporary of Beethoven and Schubert, his works remain almost unknown to this day, except for some compositions for the flute. The compositional style of the sonatas featured in this recording perfectly identifies with that of his contemporaries, while showing some differences in content; the structure of the sonatas is that of the classical period, but the use of melodic themes and harmony looks to the romantic period. These interpretations of the sonatas for flute and piano highlight the constant dialogue between the two instruments; in fact there is a continuous thematic exchange, which the artists found interesting to discover and highlight. The synergy is perceived above all in choppy tempos, while in every Adagio or Andante the flute assumes the role of the solo instrument, and the piano accompanies and responds. The themes in the slow movements are sweet and moving, and the composer manages to evoke emotions that are always different from each other, thus bringing out his predisposition for this type of tempo, present even in the most brilliant movements: in fact in every allegro, even in the one characterized by the greatest energy, there is a moment of tranquility in which the composer takes the time to make performers and listeners ponder. |

Kuhlau: 7 Flute Trios / Flute East Trio

Born in Hamburg in 1786, the son of a military bandsman, Friedrich Kuhlau showed early musical promise and took lessons with a student of CPE Bach. When Napoleon’s troops invaded Hamburg in 1810, the 24-year-old Kuhlau fled with his family to Copenhagen, and there he made his name as a pianist and composer to the royal court. Taking Danish citizenship in 1813, he worked in the vanguard of the country’s fast-moving cultural scene, enjoying huge success as a composer of operas and incidental music. Kuhlau was himself a flautist of modest accomplishment, but the popularity of salon culture in Denmark increased the demand for flute and piano music - which were both fashionable at the time - to such an extent that Kuhlau complained, in a letter to his publisher in 1829, about having too many commissions. While a flautist of modest accomplishment himself, Kuhlau wrote with unfailing craft, sympathy and imagination for the instrument and before their publication he submitted his new works for approval from the principal flautist of the Court Chapel’s orchestra. The seven trios recorded here display a surprising variety of texture and mood. Even the trio of Op.13 works from 1815 ranges from the Baroque manners of No.3’s Adagio to a much grander scale of expression in the slow introduction which opens the curtain on No.1 and on the set as a whole. There is a dashing, Mendelssohnian quality to both the melodies and the sunny disposition of the Op.86 set from 1827 which itself is set aside for a more intense, Beethovenian argument in the grand trio Op.90. In 2015 three Asian flautists founded the Flute East Trio at the Hanns Eisler Academy of Music in Berlin.

Jeroen van Veen: 24 Minimal Preludes

Over the course of musical history, the Prelude developed from a short, semi-improvised introduction to a larger scale work into a work of art in its own right. Champion of Minimal Music Jeroen van Veen writes about his preludes: “composed in a major and minor keys in the order of Chopin’s Preludes the basic idea was to see if I would limit myself to just a few chords and techniques if I could create different works.” The booklet contains informative liner notes by the composer, himself.

Geraldine Mucha: Chamber Music / Stamic Quartet, Prague Wind Quintet

Geraldine Mucha learned to read music before words; her Scottish father, Marcus Thomson, taught at the Royal Academy of Music. Having turned 18 she became a student there herself, and at a party in 1941 she met her future husband, Jan Mucha, an exiled Czech war correspondent and son of the artist Alphonse Mucha. They settled in his home city of Prague at the end of the war, but Geraldine fled the Communist regime for Scotland after the invasion of Prague in 1968, and returned only after the fall of Communism in 1989. Jirí died in 1991 but Geraldine lived on until 2012, leaving a fair-sized body of instrumental music which had been performed throughout her lifetime but is only now being rediscovered. Only one other album of Mucha’s work is available, dedicated to her orchestral music. This newly available album, made in Prague in 2015, begins with the First String Quartet which she wrote in 1944 as a recent RAM graduate: a tight, well-argued work, inflected by the fiercely rhythmic folk idiom of Janácek and Bartók. There follows a collection of seven piano works including her most extensive piece for the instrument, a set of variations on an ‘Old Scottish Song’ which also shows a thorough command of a central-European idiom. The single-movement Second String Quartet dates from 1970 opens with a keening, Scottish-accented lament: taut and concise, both concealing and saying much in a short span. The Wind Quintet is a late work, from 1998, still elegiac in mood but now balanced by the kind of dance-like flow and momentum placing it in the tradition of wind-ensemble works from Mozart to Poulenc. This carefully programmed album ends with the Epitaph for oboe and string quintet which she composed in 1991 in memory of her late husband.

Galuppi: Piano Sonatas / Damiano

| At a time when only Bach and Scarlatti were Baroque-era composers in the repertoire of pianists rather than harpsichordists, Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli pressed the cause of Baldassare Galuppi (1706-1785) with performances and recordings of sonatas. Galuppi’s style was defined during his lifetime as ‘gay, lively and brilliant’, and this description certainly capture the style of the keyboard sonatas which he wrote throughout his career. Born on the island of Burano in the Venetian lagoon, Galuppi trained with Antonio Lotti (then organist of the Basilica San Marco) and quickly became noted across Europe for a string of operatic successes which supplied both audiences and singers with dazzling entertainment. He was no musical revolutionary and continued to compose in a well-turned vein of elegant Baroque conventions while composers further north in Europe were experimenting with larger-scale forms and more daring harmonies. However, the keyboard sonatas which Galuppi wrote throughout his career delighted audiences at the time and have continued to do so since. Several collections were issued during his lifetime (and designated with Opus numbers) but a great deal of his keyboard music remains unpublished. collection of 12 three-movement sonatas, drawn from this otherwise unpublished body of work, was edited by Giacomo Benvenuti (1885-1943) and issued by the Francesco Bongiovanni publishing house in 1920, and it is from this collection (familiar to audiences of the 50s through Michelangeli) that Fernanda Damiano plays six sonatas on the present album. |

Escher: Orchestral, Chamber & Choral Music

Escher had not yet turned 30 when, in the depths of the Second World War, he began the score which would at a stroke make him the most important living composer in the Netherlands. Premiered by the Concertgebouw Orchestra in 1947, Musique pour l'esprit en deuil (1941–3) – ‘Music for the grieving spirit’ – is a 20-minute score of intense, brooding pathos, inevitably overwhelmed by the shadow of conflict and a worthy counterpart to contemporary works such as Honegger’s Liturgique Symphony. Live recordings conducted by Eduard van Beinum and Bernard Haitink have been published, but this beautifully prepared studio recording is the work of their successor as music director of the Concertgebouw, Riccardo Chailly, who did so much to reconnect the orchestra with the music of our time during his tenure.

Musique pour l'esprit en deuil is paired here with the Concerto for String Orchestra (1947-48), which attracted the admiration of John Cage, perhaps more for its surprising points of serenity than its Bartokian passages of tension and exhilarated release.

Choral music occupied a significant place in Escher’s fairly slender output. As a teacher and writer on music, a painter and a poet, Escher first thoroughly absorbed the poetry he was setting to music, then carefully devised his treatment of the words to make them both singable and understandable. His choice of poets – Paul Eluard, WH Auden, Emily Dickinson – is notable for its response to text which makes the language new again. The same is true of Ciel, air et vents, a cycle of three songs to words by the 16th-century French poet Pierre Ronsard.

This 3-CD set is part of the reissue of the most celebrated recordings from the NM Classics label.

Easy Studies for Guitar, Vol. 2/ Porqueddu

Dialogo d'Amore: Frottolas for Isabella d'Este / Falcone, L'Amorosa Caccia

The Italian frottola is an important predecessor to the madrigal and is a secular piece made up of three to four voices with instrumental accompaniment. Translating as ‘a lie’ or ‘a childish deceit’, frottolas are often simple, with repetitive melodies and homophonic textures. The frottola was immensely popular among the upper classes, in stark contrast to the other highly ornate and complex music of the Renaissance. This set sheds light on the fascinating genre. Although little is known about the composers, their music survives thanks to Ottaviano Petrucci, a prominent Venetian publisher who printed 11 anthologies of frottolas during his lifetime. The frottola emerged at the same time as Renaissance humanism, and the diversity of the genre explores the human experience, with encounters between the sublime and homespun realities and the mingling of classes and cultures. In the musical texts we find a curious melting pot of themes, ranging from popular chansons of love and nature, to proverbs and classical antiquity. Tromboncino is probably the most famous composer of frottolas, and he wrote 176 in total. He led a life fraught with criminal activity and most infamously murdered his wife, Antonia, after accusing her of adultery. He was never convicted, however, because the acting regent of Mantua, Isabella d’Este (to whom his frottolas are dedicated), was his patron and very fond of him. As for his music, Su, su leva, alza leciglia has an upbeat nature and features a clear harmonic progression in the accompaniment, foreshadowing what would later develop into Baroque era functional harmony. Meanwhile Zephyro spira e il bel tempo rimena, based on Petrarca’s poem about the Greek god of the west wind, is programmatic in its yearning melody and the ceaseless drive in its contrapuntal instrumental interludes.

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}