Anton Bruckner

416 products

-

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

PENTATONE

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

PENTATONEBruckner: Symphony No 1 In C Minor / Janowski, Suisse Romande Orchestra

This is a hybrid Super Audio CD playable on both regular and Super Audio CD players.

$21.99March 27, 2012 -

-

-

![Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 (1891 Vienna Version) / Abbado, Lucerne Festival [Vinyl]](//arkivmusic.com/cdn/shop/files/3343367.jpg?v=1749390679&width=800) {# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Accentus Music

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Accentus MusicBruckner: Symphony No. 1 (1891 Vienna Version) / Abbado, Lucerne Festival [Vinyl]

The Lucerne Festival Orchestra, under the baton of master conductor Claudio Abbado, present this new recording of Anton Bruckner’s first Symphony. The...

$45.99April 29, 2016 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Naxos

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

NaxosBruckner: Symphony No "00" / Georg Tintner, Royal Scottish

Bruckner: Symphony No. 00 "Study Symphony" & Finale to Symph

$19.99April 01, 2000 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Profil

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ProfilBruckner: Symphony in D Minor ?Die Nullte? 1869 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

Having completed a highly successful survey of Bruckner’s nine, numbered symphonies with his live recording of the Sixth in March 2013, Gerd...

$18.99November 13, 2015 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Profil

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ProfilBruckner: Symphony 6 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

Bruckner’s Sixth is one of his most genial symphonies, inhabiting a world not too distant from the symphonies of Schubert, Dvořák and...

$16.99February 10, 2015 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Profil

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ProfilBruckner: Symphonies Nos. 4 & 5 / Bohm, Staatskapelle Dresden

The first complete recordings of the original versions of the Symphonies Nos. 4 and 5 by Anton Bruckner.

$24.99February 28, 2012 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Andromeda

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

AndromedaBruckner: Symphonies Nos. 2, 5, 7 & 8

Austrian-born conductor Hans Rosbaud (1895-1962), noted champion of contemporary and Austro-German late romantic-era music, features here with an orchestra he came to...

$21.99June 10, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Profil

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ProfilBruckner: Symphonies 4, 7 & 9 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

BRUCKNER Symphonies: No. 4, “Romantic”; No. 7; No. 9 (Finale completion by William Carragan) • Gerd Schaller, cond; Philharmonie Festiva • PROFIL...

$38.99August 30, 2011 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Profil

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ProfilBruckner: Symphonies 1-3 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

BRUCKNER Symphonies: No. 1 (1866 version, ed. Carragan ); No. 2 (1872 version, ed. Carragan) ; No. 3 (1874 version, ed. Carragan)...

$32.99July 31, 2012 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Coviello

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CovielloBruckner: Symphonies 0 & 00 / Bosch, Aachen Symphony

BRUCKNER Symphonies Nos. 00 and 0 • Marcus Bosch, cond; SO Aachen • COVIELLO 31315 (SACD: 77:52) Symphony No. 0 “Cancelled”: Bruckner...

$21.99January 28, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleLinn Records

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleLinn RecordsBruckner: Symphonie No. 2 / Pinnock, Royal Academy Of Music Soloists Ensemble

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 2 (arr. Payne). J. STRAUSS II Wein, Weib und Gesang (arr. Berg) • Trevor Pinnock, cond; Royal Academy of...

March 25, 2014$21.99$16.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

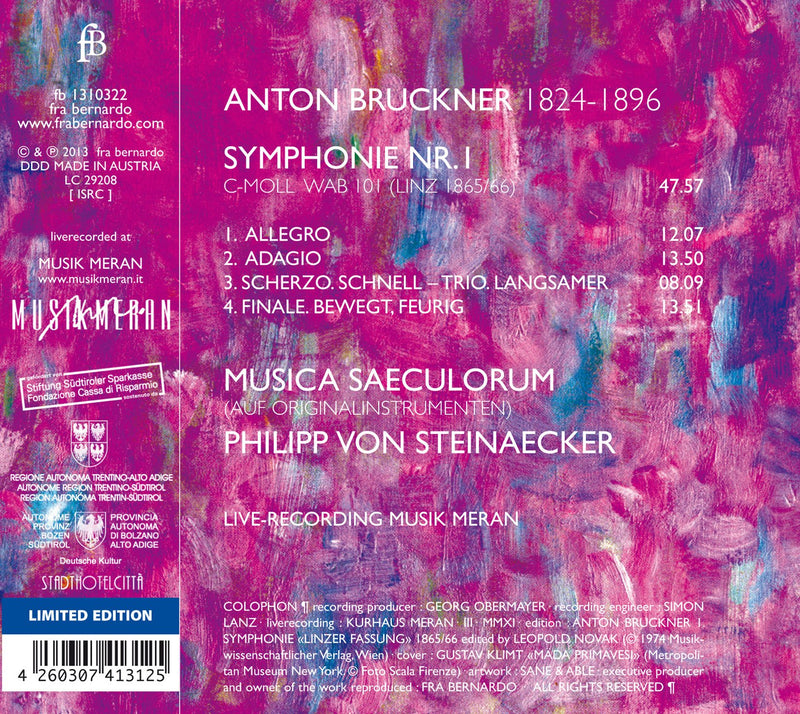

Fra Bernardo

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Fra BernardoBruckner: Symphonie No. 1

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 1 (1866 vers) • Philipp von Steinaecker, cond; Musica Saeculorum • FRA BERNARDO 1310322 (47:57) Live: Musik Meran The...

$20.99January 28, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Gramola Records

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Gramola RecordsBruckner: Symphonie 8 / Ballot, Upper Austrian Youth Orchestra

"This may not be the best performance of Bruckner's Eighth, but it has become the one I most cherish, because it is...

$31.99January 13, 2015 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

MDG

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

MDGBruckner: String Quintet, Etc / Rohde, Leipzig Sq

Classical Music

$23.99January 01, 2005 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Naxos

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

NaxosBruckner: Motets / Robert Jones, Choir Of St. Bride's Church

BRUCKNER: Motets

$19.99January 04, 1995

Bruckner: Symphony No 1 In C Minor / Janowski, Suisse Romande Orchestra

This is a hybrid Super Audio CD playable on both regular and Super Audio CD players.

Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 (1891 Vienna Version) / Abbado, Lucerne Festival [Vinyl]

Bruckner: Symphony No "00" / Georg Tintner, Royal Scottish

Bruckner: Symphony in D Minor ?Die Nullte? 1869 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

I was unfamiliar with this symphony but reassured by my instant recognition of some very Brucknerian tropes in the opening bars which heralded a surprisingly mature and rewarding work; perhaps it is for this reason that although he initially disowned it, Bruckner apparently tacitly acknowledged its worth by eventually bequeathing the manuscript to the Linz state museum. The opening motif is a persistent, scurrying, semiquaver figure over a sombre march and punctuated by stately, defiant brass chords, all very proleptic of the beginning of the Third Symphony. Ultimately a magnificent climax is underlined by a characteristic Brucknerian pause of six beats and we thus remain on familiar territory.

The calm, richly harmonised introduction to the Andante creates a bucolic or pastoral atmosphere, followed by a first falling, then rising, chromatic theme which is passed around the orchestra from the cellos to the woodwind to the flute to the strings. The Scherzo is typically rumbustious and faintly menacing; the Finale is grand but slightly stilted and disjointed; perhaps the least successful movement. Indeed the comparatively short measure of the symphony’s movements – at least by Bruckner’s later standards – may perhaps partially be explained by his inability or unwillingness at this stage of his symphonic career to trust the material to longer development. For all its grandeur, it does not aspire to the cosmic “heavenly length” of the Fifth or the Eighth.

Nonetheless, this is a thoroughly enjoyable work, superbly played by an orchestra which set the highest standards in its Bruckner cycle and in the same warm, spacious, first-rate sound we have come to expect. It's another live recording in the more accommodating venue of the Regentenbau and without the challenge of the reverberation attendant upon the recording of those symphonies performed in Ebrach Abbey.

- Ralph Moore, MusicWeb International

Bruckner: Symphony 6 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

Bruckner: Symphonies Nos. 4 & 5 / Bohm, Staatskapelle Dresden

The first complete recordings of the original versions of the Symphonies Nos. 4 and 5 by Anton Bruckner.

Bruckner: Symphonies Nos. 2, 5, 7 & 8

Bruckner: Symphonies 4, 7 & 9 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

BRUCKNER Symphonies: No. 4, “Romantic”; No. 7; No. 9 (Finale completion by William Carragan) • Gerd Schaller, cond; Philharmonie Festiva • PROFIL PH11028 (4 CDs: 214:16) Live: Erbrach 7/29/2007, 7/29/2008, 8/1/2010

The main interest here will be in William Carragan’s completion of Bruckner’s extensive sketches for the finale of the Ninth. The completion supplies architectural context for the first three movements, thus providing a valuable corrective to posterity’s deeply ingrained perception of this symphony as “unfinished,” like Schubert’s Eighth (coincidentally, both “ending” with a slow movement in an exotic, otherworldly E Major). That said, I find myself ambivalent about the enterprise for two reasons. First, the quality of the existing music: Although Bruckner left a lot of the movement in a relatively advanced state of sketching—the complete exposition and substantial portions of the development and recapitulation—much of the thematic content itself nevertheless leaves an arid, underdeveloped impression that (to my ears) fails to approach the level of the preceding movements. If he had lived to do more with it, he would surely have transformed it far beyond its existing state. More seriously, much of the movement is completely missing (including all of the coda); in contrast to the finale of Mahler’s 10th, we lack any kind of comprehensive blueprint to work with, in the form of a continuity draft for the entire movement. Carragan’s completion comes into competition with an alternative one by Nicola Samale and Giuseppe Mazzuca, which has been recorded by Eliahu Inbal and the Frankfurt Radio Orchestra (Teldec). Given the lack of any concrete sketches for the coda, any conjectural realization will effectively be an original composition. Carragan’s coda is longer and more imposing than Samale-Mazzuca’s, using, in addition to thematic recalls from the first movement, references to the first movement of the Eighth, as well as borrowing the chorale-apotheosis strategy from the finale of the Fifth.

This performance is billed as the recorded premiere of Carragan’s 2010 revision, but his own notes don’t offer any information on how it differs from his earlier version. That was recorded in 1996 by Yoav Talmi with the Oslo Philharmonic (Chandos), but since I don’t know that recording I can’t comment on differences. In any event I’m glad to have both the Carragan and Samale-Mazzuca completions. Another tack is taken by Harnoncourt and the Vienna Philharmonic (RCA, live), who present Bruckner’s sketches in the format of a lecture-recital, without adding anything (spoken commentary in both German and English)—here, I must confess I find their breaking off with the end of the sketches a more moving experience than anyone’s entirely conjectural original composing.

So there’s much of interest here, although I would have thought that a release of the Ninth alone might have been a more competitive proposition—how many prospective purchasers will really want yet another Fourth and Seventh played by a less-than household-name conductor and orchestra?

Happily, the performances are consistently fine ones that will grace any Bruckner collection. The Philharmonie Festiva is none other than the famous Munich Bach Orchestra, augmented for the purpose by players from the other Munich orchestras. They make a handsome sound—rich, sweet, recognizably Bavarian. The recorded acoustic (the Abbey Church in Ebrach) is ideal for Bruckner, reverberant but with plenty of bite and detail.

The Fourth is lyrically shaped with a natural flow, played straight with little deviation from the initially established tempos, though by no means inflexible. There are many imaginative details, starting with the evocatively tapered horn phrases at the opening. Indeed, the brass playing throughout is of exceptional quality, conjuring the work’s forest atmosphere most effectively. I occasionally miss the stronger interpretive profile of the great Bruckner conductors of the present and recent past (e.g., Abbado, Dohnányi, Harnoncourt, Wand)—as in the Andante, whose grey expanses don’t have quite enough tension to my ears.

The Seventh also goes beautifully, with a singing intensity, transparent textures, and an atmospheric first-movement coda. The Adagio has an attractive quality of breathing spontaneity, and an ear-catching sheer beauty of sound, from the thrilling amplitude of the C-Major climax to the purple-hued low brass in the coda. Schaller captures the Scherzo’s rustic Schwung in rich colors and biting detail, while his finale is less febrile than usual (13:00) with perhaps just a hint of stolidity.

As for the familiar portion of the Ninth, the first movement is beautifully lucid with much absorbing textural detail—for example, in the thickly scored stretches of the exposition’s closing section (Rehearsal G ff.), or the nightmarish march episode inserted into the recapitulation (Rehearsal O ff., A?-Minor). Altogether the music’s keel comes across as slightly too even, including a noticeable tendency to smooth out Bruckner’s injunctions to short articulations (for instance, in the quickening woodwind figure at Rehearsal A, along with the preceding violin motive in quarter notes, mm. 28 ff.). The Scherzo is taken slower, and is less demonic in character, than usual, but still very powerful in its smooth, weighty way. The E-Major Adagio is straight, lucid, and lyrical, well shaped and sonorously imposing, if expressively less febrile than some.

Overall, these are high-quality performances of much distinction, and the rarity of Carragan’s completion makes the set a desirable proposition for Bruckner collectors.

FANFARE: Boyd Pomeroy

--------

These performances were given at the Ebrach Summer Music Festival as part of the Bruckner Festival in 2007, 2008 and 2010. In co-operation with Bavarian Radio the recordings were made in the glorious setting of the Ebrach Abbey church in Bavaria which on this evidence has a splendid acoustic.

The Philharmonie Festiva may be a new name to many readers. This is a highly accomplished orchestra comprising mainly members of the Munich Bach Soloists augmented by musicians from the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Munich Philharmonic. Taking the baton is Bamberg-born conductor Gerd Schaller who is the founder and musical director of the Ebrach Summer Music Festival.

The performance of the Ninth Symphony contains the first recording of the revised 2010 version of the finale completed by William Carragan. Carragan is a contributing editor of the Anton Bruckner Collected Edition and has prepared a new edition of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 2. From 1979 to 1983 he worked on a finale for the Bruckner Ninth. That first completion can be heard from the Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yoav Talmi on Chandos CHAN 8468/9 but revisions also followed in 2003 and 2006.

Composed in 1874, the Symphony No. 4 in E flat major, known as the Romantic, has been given wholesale revisions at various times. The 1878/1880 version recorded on this disc has been described by composer and musicologist Robert Simpson as, “ clean and lean”. The memorable opening under Gerd Schaller is marvellously done; immediately convincing. Schaller’s pacing is impressive navigating the flow and broad sweep of the writing with broad assurance. The horns have a significant part throughout and the Philharmonie Festiva brass is in impressive form displaying a burnished tone.

Composed in 1881-83, the Symphony No. 7 in E major is the most popular of Bruckner’s symphonies and it brought the composer the greatest success he had known. It was Arthur Nikisch who conducted the première at Leipzig in 1884. Schaller attains great nobility in a performance that leaves a powerful effect. The orchestral climaxes are remarkable with Schaller astutely building the tension from calm hush to furious climax.

Bruckner was working on his Symphony No. 9 in D minor at the time of his death in 1896. The first three movements were completed with sketches left for a fourth. Bruckner said, “ I have served my purpose of earth; I have done what I could, and there is only one thing I would still like to be granted: the strength to finish my Ninth Symphony.” At Bruckner’s own suggestion the unfinished symphony was often performed with the Te deum serving as the final movement. For this Ebrach Abbey performance Schaller uses the revised 2010 version of the final movement as completed by William Carragan. In this reading I was struck how confidently Schaller demonstrates a real understanding of the score’s structure. There’s a splendid clarity about his reading. In addition I love the way Schaller emphasises the spiritual qualities especially in the gloriously played second movement Adagio.

This is a really impressive release. The engineers have done a remarkable job providing a clear, well-balanced sound. There are decent notes in the booklet. Carragan’s completion of the Ninth Symphony is an added attraction.

-- Michael Cookson, MusicWeb International

Bruckner: Symphonies 1-3 / Schaller, Philharmonie Festiva

BRUCKNER Symphonies: No. 1 (1866 version, ed. Carragan ); No. 2 (1872 version, ed. Carragan) ; No. 3 (1874 version, ed. Carragan) • Gerd Schaller, cond; Philharmonia Festiva • PROFIL PH12022 (3 CDs: 192: 19)

Gerd Schaller and William Carragan want to show us another side to Bruckner. Carragan has edited each of the symphonies, drawing as far as possible on the earliest surviving versions, and Schaller is recording a cycle based on the resulting editions. This is the second of three box sets, the first of which included the Ninth Symphony with Carragan’s completion of the finale.

The editorial issues associated with the first three symphonies are just as thorny. Carragan justifies the project in a liner note essay by saying that these symphonies are best known in their later versions, and that the earlier versions are ripe for reappraisal. That’s a generalization at best; the third may be better known in its later form, but the early versions of the first two symphonies seem to predominate these days.

But how early is early? Carragan contends that most performances of the early versions include later revisions. His edition reproduces, as far as possible, the earliest complete conceptions of these works, which he dates to 1866, 1872, and 1874, respectively. (The most commonly performed ‘early’ versions of the symphonies date from 1877, 1873, and 1876.) It is hard to hear exactly what Bruckner thought fit to revise here. His changes involved evening out the phrase structure and modifying the orchestration. He also extended many passages, especially introductions, and took out the most overt references to Wagner, as well as much of the counterpoint, in the third symphony. Carragan’s most radical departure is to place the Scherzo of the second symphony before the Adagio , but otherwise his edits mainly concern details of counterpoint and orchestration.

None of the alleged flaws seriously impede these early versions. Some passages are more abrupt than we might expect, but each symphony is a work of focused conception and impressive realization. Gerd Schaller gives convincing interpretations. He has a vested interest in Carragan’s work, as the third symphony was edited at his request, and the version receives it premiere recording here.

The only problem is that the conductor’s respect for this scholarship weighs down his readings with an undue sense of reverence. The performances are tightly controlled, with the orchestra always kept on a tight leash. Schaller also holds back on the tempos in almost every movement. Could this be another result of Carragan’s research, or simply a matter of personal taste? Whichever way, it is not a serious problem. In fact, Schaller demonstrates to his more intemperate colleagues that momentum and excitement can be maintained without the need for fast tempos or dynamic extremes. The Scherzo of the first symphony, for example, and the opening of the second, both have all the power and energy they need, despite the relatively slow speeds. The only danger is that the music can sound a little too civilized; classical elegance is an underrated virtue in Bruckner interpretation, but in the finales of each of these symphonies, Schaller is just a little too formal and restrained. Fortunately, the elemental power he can summon from his orchestra for the tuttis and climaxes ensures that nothing ever sounds superficial.

The orchestral playing is excellent throughout, and whatever you might think of either the editions or the interpretations, both are afforded credibility by the commitment of the players. Schaller ensures that ensemble and balance are carefully regulated, so when, for example, the string melody is briefly obscured by the brass in the first symphony Adagio , you can be assured that this is a deliberate and only transitory effect, and so it proves.

These recordings will appeal most to Bruckner specialists with an interest in Carragan’s new editions. The details of his changes are well served by both the precise playing and the patient, controlled conducting. But those looking for an introduction to Bruckner’s early symphonic works—in early or late versions—would probably be better served by more passionate accounts.

FANFARE: Gavin Dixon

Bruckner: Symphonies 0 & 00 / Bosch, Aachen Symphony

BRUCKNER Symphonies Nos. 00 and 0 • Marcus Bosch, cond; SO Aachen • COVIELLO 31315 (SACD: 77:52)

Symphony No. 0 “Cancelled”: Bruckner doesn’t exactly go out of his way to sell this Symphony to us, does he? But, as the tortuous revision histories of many of his symphonies demonstrate, the composer’s painfully self-critical attitude to his own works is never a reliable indicator of their worth. In fact, the Zero Symphony postdates the First and, to my ear at least, is superior, closer in spirit to the Second and Third, if not quite as involved, nor as long. The “Studiensinfonie,” No. 00, by contrast, is very much an early and exploratory essay in the form. It is a kind of graduation piece, written in 1863, immediately after the end of Bruckner’s studies with Otto Kitzler. Given Bruckner’s stylistic trajectory over the course of his numbered symphonies, we might expect to hear the influence of Schubert and Haydn here, but in fact Schumann and Mendelssohn are stronger voices. In No. 0 we hear Bruckner’s mature musical personality, perhaps not yet fully formed but clearly recognizable. In No. 00 we have to strive much harder to make the connection, although there are plenty of clues in the detail.

My first exposure to the Zero Symphony was via a recording from Stefan Blunier and the Beethoven Orchester Bonn (MDG 937 1673-6). Blunier makes a good case for the work, not making any concessions for its early date, seeking out, and often finding, the depths of expression we more naturally associate with the later symphonies. But this new version from Marcus Bosch is even better, slicker, better structured, and more dramatic all around. The most significant difference between the two versions is in the tempos; Blunier takes 50:11 while Bosch is finished in 41:23. Yet Blunier never feels lethargic, nor does Bosch feel rushed. Both apply a good deal of rubato, allowing for supple and naturally shaped phrases at their respective speeds. Both orchestras play well, and both are captured in excellent SACD audio. Bosch is a little stiff in the second movement Andante (despite its tempo marking a clear ancestor of the great adagio s of the late symphonies) and the phrases occasionally feel clipped. However, the rest of his interpretation is excellent, particularly the Scherzo, which he drives home with thundering intensity, and the Finale, which is dramatic, varied, and nuanced throughout.

Symphony No. 00 is a more modest conception, and Bosch is wise to avoid the extremes that he applies to the later work. But his reading isn’t exactly “Classical” either. There is still plenty of rubato, and he is generous with the freedom he allows the woodwind soloists (more prominent here than any of the composer’s later works). There is no getting away from the fact that this is a minor work, but Bosch makes the best possible case for it.

This release marks the end of a complete Bruckner symphony cycle from Marcus Bosch and his Aachen forces. The project has been on the go since 2003, when an Eighth Symphony recording was so well received that it gradually brought about an entire cycle. Coviello claims that this is the first complete Bruckner cycle on SACD. That may or may not be the case, but the “complete” appellation is certainly appropriate; not only are these two early symphonies included, but there is also a Finale for the Ninth Symphony, edited by Nicola Samale, Giuseppe Mazzuca, John A. Phillips, and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs.The way Bosch approaches Bruckner is unlikely to be to everybody’s taste, his tempos are generally fast, although he’s not of the “revisionist” school: However fast he takes the music there is always plenty of ebb and flow, and usually very wide-ranging dynamics. Of the releases I have heard, my favorite is the Second Symphony. Like the Zero Symphony here, Bosch demonstrates through his impassioned but controlled performance that the Brucknerian tendencies of the late symphonies are just as evident early on, they just need a committed interpreter who doesn’t make concessions to their slightly narrower musical vocabulary. Most of the cycle was recorded in the church of St. Nikolaus in Aachen, which has proved an ideal acoustic, the reverberance round and clean, adding further gravitas to Bruckner’s quasi-liturgical statements. This recording was made in a different Aachen church, St. Michael, which I assume is smaller. It is certainly equally appropriate to the music at hand.

A box set of the entire cycle was issued at around the same time as this release. Although Bosch’s fast tempos might make some of the individual movements less attractive, I suspect that, in its entirety, the cycle will be well worthwhile, especially for the sheer drama he draws from this music, the quality of the orchestra, and of the recorded soundscape, both from the acoustic itself and the SACD engineering. Of the individual discs, the early symphonies deserve the highest recommendation, the Second Symphony in particular, but also this, although chiefly for the Zero Symphony, by far the finest of the two compositions on the disc.

FANFARE: Gavin Dixon

Bruckner: Symphonie No. 2 / Pinnock, Royal Academy Of Music Soloists Ensemble

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 2 (arr. Payne). J. STRAUSS II Wein, Weib und Gesang (arr. Berg) • Trevor Pinnock, cond; Royal Academy of Music Soloists Ens • LINN 442 (SACD: 65: 39)

A Bruckner symphony arranged for chamber orchestra? That really shouldn’t work—but it does, and it’s a spectacular success. Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, principal of the Royal Academy of Music, is the brains behind the project, and top honors go to him for his astute choice of symphony and even more astute choice of arranger, the composer Anthony Payne. Add to that the arrangement itself, which is a triumph of clarity and timbral focus, an interpretation from Trevor Pinnock, who proves to be an insightful Brucknerian (who knew?), orchestral playing from students who need fear no comparisons with the finest professionals, and exceptional SACD audio, and the result is an unqualified success on every count.

The release is the second in a series called Reigniting Schoenberg’s Vision . The idea is to recreate—or even reinvent—Schoenberg’s famous Society for Private Musical Performances, performing some of the chamber arrangements of symphonic works made for those events, and even, as in this case, correcting Schoenberg’s omissions by adding to the repertoire. Bruckner’s Second “Symphonie” (as it’s referred to throughout the accompanying literature, a curious affectation) is a daring but smart choice. While it is not particularly small of stature, its identity, character, and charm emanate more from its quieter passages than from its climaxes. Payne follows the spirit more than the letter of the Schoenberg/Berg/Stein arrangements, using a 20-piece ensemble, larger than in any of the Vienna reworkings, but substituting the full orchestra in similar ways, particularly in the use of piano and harmonium to provide essential, although usually invisible, support.

Some of the climaxes feel underpowered, but even here the pros of the arrangement outweigh the cons. We hear the stratospheric violin lines, the chugging bass figures, and the brass fanfares with a rare clarity. But it is in the quieter passages that this version really comes into its own. At the start, for example, the theme is given to the cellos. Here, we hear it as a cello solo, elegantly phrased and all the more beautiful for the sense of intimacy a single player can bring. In later passages, the bassoon writing is a particular revelation, and just as beautifully played. The opening of the Andante second movement, pared down to string sextet, is transporting in a way that only the very finest recordings of the full symphony manage. Some of the scherzo sounds a little hollow, but Pinnock and his small brass section ensure the momentum is maintained through finely calibrated accentuation. And in the finale, an appropriate gravitas is achieved, even in the absence of weight.

Trevor Pinnock brings many of the preoccupations of the period instrument movement to bear on the work, yet it never sounds dry. Details of phrasing and accentuation are addressed in every bar, and the smaller ensemble allows him to shape and color accompanying textures with as much care as the main themes. His tempos are propulsive, but never rigid, nor excessively fast. He seems to be in a quandary over the caesuras. The tutti cut-offs don’t need the time to decay, but the severity of the mood changes often require a pause for reflection, which he always gives.

The instrumentalists perform to an exceptionally high standard throughout. The playing of the string sextet is particularly impressive, highly expressive but finely controlled and balanced. So too the woodwind soloists, blending their tone in ensemble but taking full advantage of the increased exposure in solos to play with character and color. To all the other accolades for Jonathan Freeman-Attwood we must also add recording producer, another field in which he excels. The recording was made at St. George’s Bristol, and the sound is warm, but never excessively resonant. The clarity that Payne achieves in his arrangement is amplified at every step by the quality of the recorded sound.

If I’ve one grumble, it’s with the coupling, Alban Berg’s arrangement of Wine, Women, and Song . It follows hard on the heels of the Bruckner without any gap at all (not even time to jump up and switch it off) and it adds little. In comparison to Payne’s detailed and clear textures in the Bruckner, Berg’s arrangement feels bloated and unfocused. Berg had a different acoustic in mind of course, and a different setting in every sense. Presumably this arrangement is included to highlight the link with the Society for Private Musical Performances, but it’s unnecessary. Whatever inspiration Freeman-Attwood, Payne, and the RAM musicians have drawn from Schoenberg is of only historical interest as far as this recording is concerned: The project needs no further justification than the exceptional quality of the results.

FANFARE: Gavin Dixon

Bruckner: Symphonie No. 1

BRUCKNER Symphony No. 1 (1866 vers) • Philipp von Steinaecker, cond; Musica Saeculorum • FRA BERNARDO 1310322 (47:57) Live: Musik Meran

The program notes to this recording state that the 60-person Musica Saeculorum opted to record Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1 in its original 1866 edition on period instruments in an effort “to identify any possible connection to Schubert and the early Romantics.” Harmonically, of course, Bruckner is worlds removed from Schubert and his contemporaries. But the use of period instruments does offer Bruckner a slightly more subdued timbral palette than most listeners are accustomed to in his music. The strings are somewhat darker, the brass a bit more veiled. Whether because of instrumentation, recording engineering, or conducting choices, though, I find that the strings have a tendency to overbalance the other instruments in tutti sections, occasionally making melodic material difficult to discern. This is my primary criticism of this disc. Bruckner at his most forceful can and should be overwhelming, but the counterpoint should always be clear; his tuttis mark the apotheoses of thematic material. In this recording, these passages tend to be rather murky and undifferentiated.

This criticism aside, Philipp von Steinaecker demonstrates a keen understanding of Bruckner’s aesthetic. The dotted rhythms of the first movement’s main theme are crisp and energetic, as are the horn’s responses. Von Steinaecker lingers appropriately on Bruckner’s extended passages of dominant harmony, building harmonic tension through strategic ritards in preparation for majestic statements in the brass. Even within string passages, though, figuration occasionally overshadows melody, as in the contrapuntal development of the first theme in the violins against sextuplet scales in the lower strings or the recapitulation of the second theme in the basses against eighth-note figuration in the upper strings. The modulatory passages that follow, however, are forceful and stern, and the rush to the final bars is quite exciting, though I would have liked the thematic material in the winds to be clearer.

Von Steinaecker’s is one of the more expansive readings of the symphony’s second movement, over a minute longer than Jochum’s. I find the expansiveness effective; the chromatic introduction becomes nebulous enough to make the eventual arrival of stable tonality a genuine relief. In the soaring passages that follow, though, minimal differentiation is made between melody and accompaniment. Von Steinaecker is sensitive to the ebb and flow of harmonic tension, but the melodic contours are lost throughout much of the movement.

The third movement is perhaps the most successful, with strong, almost violent accents and sharp contrasts in dynamics. At nearly a minute shorter than Jochum’s performance and 90 seconds briefer than Barenboim’s, it is among the more energetic recordings of this movement. I only wish that the brass dissonances toward the end received more weight. And the trio has the same problems with balance as the previous two movements: the motivic fourths in the horn are quite difficult to hear.

The fourth movement has almost no balance issues, although Bruckner’s orchestration is not particularly different in this movement than in the others. The opening pages are powerful and imposing, though I would have liked von Steinaecker to take an even greater ritard over the extended dominant harmonies that precede the second statement of the first theme. The second theme, stated in the violins with offbeat accents in the basses, is appropriately rustic. Likewise, von Steinaecker builds tension admirably before Bruckner’s characteristic pauses. The development maintains a consistent sense of direction. Von Steinaecker is particularly effective in his treatment of Bruckner’s obsessively-repeated scale fragments in the strings, which he leads gradually from background to foreground against the melodic material in the horns. The ending is triumphant and grand, though a broader ritard before the final cadence would have made it more so.

Because of the balance issues mentioned above, I cannot give this recording a wholehearted recommendation, but von Steinaecker’s conception of the piece is intelligent and appealing. The sound is generally crisp and live, with very slight tape hiss apparent at the beginnings and ends of tracks.

FANFARE: Myron Silberstein

Bruckner: Symphonie 8 / Ballot, Upper Austrian Youth Orchestra

-- Richard Lehnert, Stereophile

It is perhaps no coincidence that the duration of this performance runs to what will seem to many an extreme and etiolated 104 minutes. That would be unprecedented, were it not for the fact that the timings overall and for individual movements match almost exactly those of the recording made by Sergiu Celibidache with the Munich Philharmonic for EMI in 1993. I do not know if Celibidache was in any sense Rémy Ballot’s mentor, but Ballot certainly studied briefly under him in Paris in the 1990s and this recording suggests that he imbibed the precepts of that eccentric maestro.

Comparisons with other recordings are to some degree otiose, insofar as no other recording apart from Celibidache’s begins to approach the leisureliness of this one but the other recordings this most resembles include the two by Karajan, especially the earlier one from 1957, Giulini’s two recordings from 1984 with the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic respectively, and Gunter Wand, also with the BPO in 2001. These are all massive, vertical interpretations aspiring to transcendence, as opposed to the fleeter, nimbler versions by such as Tennstedt, R?gner and even Furtwängler, using his own adaptation of the 1892 Haas edition.

Obviously the edition chosen has an impact on timings, too. Both Ballot and Celibidache employ the 1890 Nowak version yet even the slowest of the other recordings that use this same score is still over a quarter of an hour faster then theirs, while many are as much as half an hour shorter. Even those recordings which use either the most complete Nowak edition of the original 1887 score, or the somewhat longer edition of the 1890 score produced by Robert Haas, or even the elaborated version as recorded by Schaller, do not begin to approach Ballot for expansiveness. Nor is comparison with many excellent historical recordings, such as those by Knappertsbusch, very valid, as they invariably used the revised and heavily cut first performance version of 1892.

If this preamble sounds like a critical caveat to the consumer against trying this recording, I hasten to add that I am merely trying to establish its uniqueness and am in no sense implying that excuses have to be found for Ballot’s tempi - although a predisposition on the part of the listener to tolerate them would be an advantage. Ballot carries off his vision of this symphony triumphantly; the weight and dignity of this monumental account enhance my conviction that it is the greatest Romantic symphony in the canon.

Of the twenty or so different recordings with which I am familiar, five of the best are with the BPO and three with the VPO, suggesting that the presence of a first tier orchestra steeped in Brucknerian tradition is of paramount importance – yet the virtuosity of the Upper Austria Youth Orchestra rides a coach and horses through that notion. Their talent and technical prowess are phenomenal, and there are certainly no more blips or minor flubs than one would expect to hear in any live performance by a first rate professional band. The notes tell us that 130 musicians with an average age of seventeen took part in this performance, although only 96 are named; presumably there were more guest instrumentalists than are credited and they make a magnificent sound. Nonetheless, it is undeniable that despite their prowess, they cannot quite emulate the security of attack or the silky sheen that Karajan’s orchestras achieve, and despite the emphasis conductor Ballot’s places in the notes upon the importance of varying dynamics, nor is their ability to shade them quite so subtly responsive.

This performance took place in the same location almost a year to the day after the Third Symphony was recorded live and subsequently released on Gramola label; I reviewed it here very favourably. The Ninth will follow later this year and the Sixth in 2016. The resonant acoustic of the Stiftsbasilika favours and even demands slower speeds if the articulation of faster passages is not be obscured by the reverberation. By all accounts, the recording engineers are better able to sift and clarify the sound than human ears listening live can process it; certainly there is no “sonic mush” here to trouble the listener. Inevitably, given the live location, this recording cannot match the transparency Karajan achieves in the studio but the sound remains rich and round, if slightly veiled. Coughing is minimal and there is no recurrence of the hum from the lighting which mildly marred the recording of the Third last year.

In many ways, the sum of this performance is greater than its parts: it clearly greatly impressed those present and remains mightily impressive as a recording per se and as a memento of what was evidently a great event, even if at individual points other interpreters are more effective – or simply different. Thus in the mighty, brooding opening, Karajan, Giulini and Furtwängler generate more tension, while Tennstedt or Maazel are more urgent and imploring, whereas Ballot tends to slow down marginally before the big moments such as the climaxes to the brass crescendos in order to emphasise and underline their impact. The Totenuhr, too, is especially chilling, dwindling spectrally into nothingness, its graduated dynamic beautifully judged.

Despite its length, there is absolutely no sense of dragging in the Scherzo and indeed some of the additional time is accounted for by Ballot sharing Thielemann’s attachment to making the pauses count, allowing the reverberation to fade and an expectant silence to prevail. The ostinato of falling fifths is superbly articulated. The distension of the Adagio represents the most daring of the risks Ballot takes with this music and but the results are heavenly. It is true that sometimes the young string-players do not “bow through” their phrases sufficiently to emulate the richness of tone their senior counterparts generate and the sustained phrases begin to fade and sag very slightly in comparison with the shaping of Wand or Karajan, but Ballot succeeds magnificently in creating a breathless hush, the descending octaves from the flutes hanging in the dusk like floating flares.

The finale is in many ways the most impressive movement of all. Ballot’s grip on phrasing, his exploitation of pauses and his meticulous care over dynamics results in a wholly satisfying melding of its four, disparate main themes into a coherent cosmic narrative. The din of the clashing cymbals in the final orchestral climax is overwhelming. Whatever your reservations regarding the arguable excesses of Ballot’s concept of this masterwork, this is a recording that every committed Brucknerian should hear.

A couple of pedantic niggles regarding the notes and their translation: Bruckner’s “Faszination für Zahlen” is rendered literally as his “fascination for numbers” when of course the correct preposition should be “with” if the sense intended is not to be reversed to mean that it is the numbers who are fascinated by Bruckner. Secondly, a critic is quoted as presumably favourably describing the Youth Orchestra as “[n]icht irgenwelche ästhetisch kaum erreichbaren Wiener, Berliner oder Münchner Philharmoniker”, which is translated into English as “not some aesthetically unapproachable Vienna, Berlin or Munich Philharmonic”. Apart from the fact that I cannot understand what is meant by the phrase in either language, “aesthetically unapproachable” sounds like a back-handed compliment, as does “scarcely accessible” – unless the sense is “irreproachable”.

-- Ralph Moore, MusicWeb International

Bruckner: String Quintet, Etc / Rohde, Leipzig Sq

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

![Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 (1891 Vienna Version) / Abbado, Lucerne Festival [Vinyl]](http://arkivmusic.com/cdn/shop/files/3343367.jpg?v=1749390679&width=800) {# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}