Mieczysław Weinberg

61 products

-

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Grand Piano

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Grand PianoWeinberg: Complete Piano Works, Vol. 3

While Weinberg was establishing his reputation in Moscow with serious music, he also composed twenty-three charming miniatures to meet the demand for...

$19.99October 30, 2012 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Grand Piano

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Grand PianoWeinberg: Complete Piano Works, Vol. 4

The last disc in Brewster Franzetti's highly acclaimed four single disc survey includes the deeply expressive, technically challenging and superbly varied Sonatas...

$19.99February 26, 2013 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOWeinberg: Cello Concerto, Op. 43; Fantasy, Op. 52 & Concertino Op. 43bis / Borowicz, Kristiansand Symphony

Mieczyslaw Weinberg grew up in Warsaw, a city in which Poles then accounted for two thirds of the populace and Jews for...

$18.99July 03, 2020 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOWeinberg: Piano Sonatas Opp. 8, 49bis & 56 / Blumina

The Echo Klassik prizewinner Elisaveta Blumina numbers among the outstanding female musicians of the younger generation who pursue their own paths, unaffected...

$18.99June 08, 2018 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleCPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleCPOWeinberg: Works for Violin & Piano, Vol. 2 / Kirpal

This is the second volume of Mieczyslaw Weinberg's works for violin and piano. Weinberg's Violin Sonata No. 1 covers the path from...

October 14, 2016$36.99$25.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

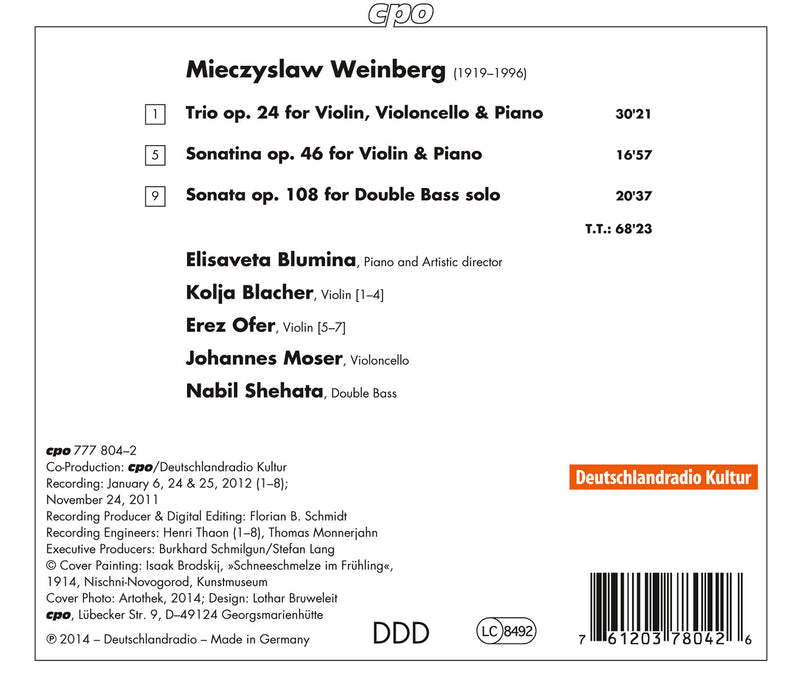

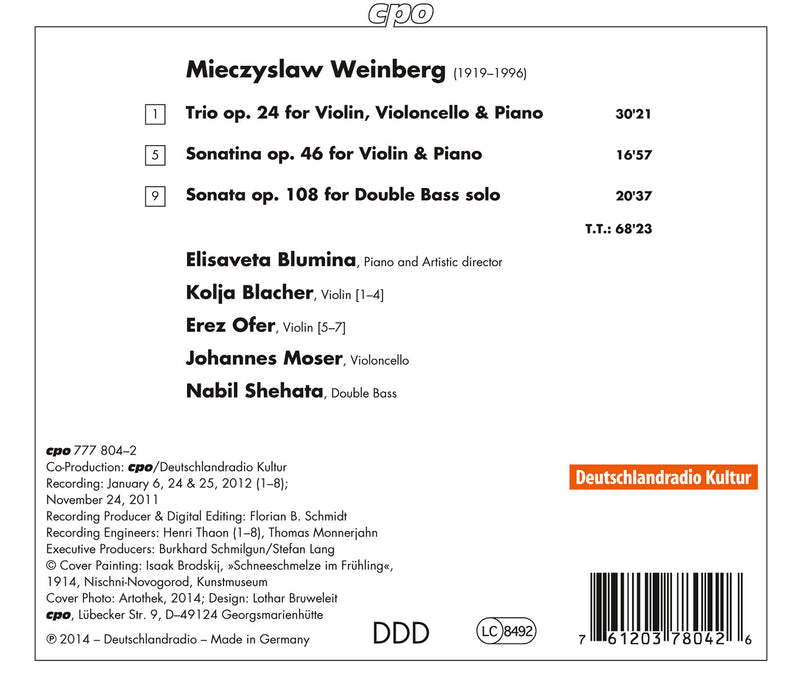

CPOWeinberg: Piano Trio; Violin Sonatina; Double Bass Sonata

WEINBERG Piano Trio. 1,2,4 Sonatina for Violin and Piano. 1,3 Sonata for Solo Bass 5 • 1 Elisaveta Blumina (pn); 2 Kolja...

$18.99April 29, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOWeinberg: Complete String Quartets / Danel Quartet

WEINBERG String Quartets Nos. 1–17. Capriccio. Aria • Qrt Danel • CPO 777913 (6 CDs: 436:41) If you’ve not been collecting CPO’s...

$58.99April 29, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Capriccio

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

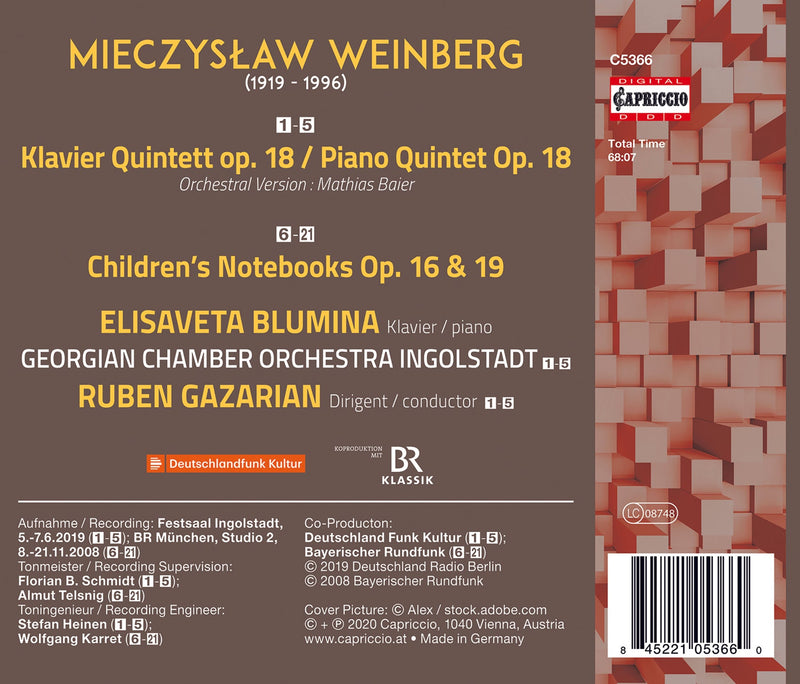

CapriccioWeinberg: Piano Quintet (Orchestral Version) - Children's Notebooks, Books 1 & 2 / Elisaveta Blumina, Ingolstadt Georgian Chamber Orchestra

Five years after Shostakovich premiered his quintet to turbulent success in 1940, his new 24-years young friend Weinberg premiered one of his...

$21.99October 02, 2020 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

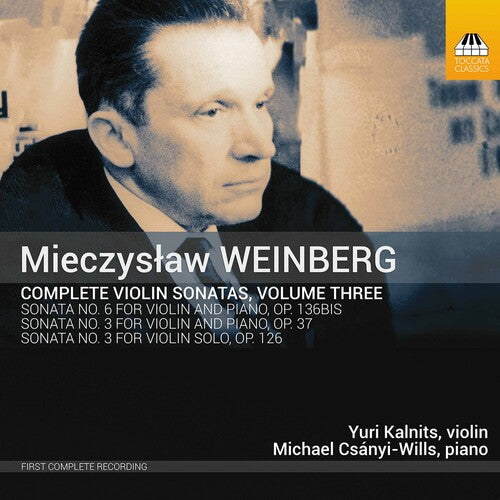

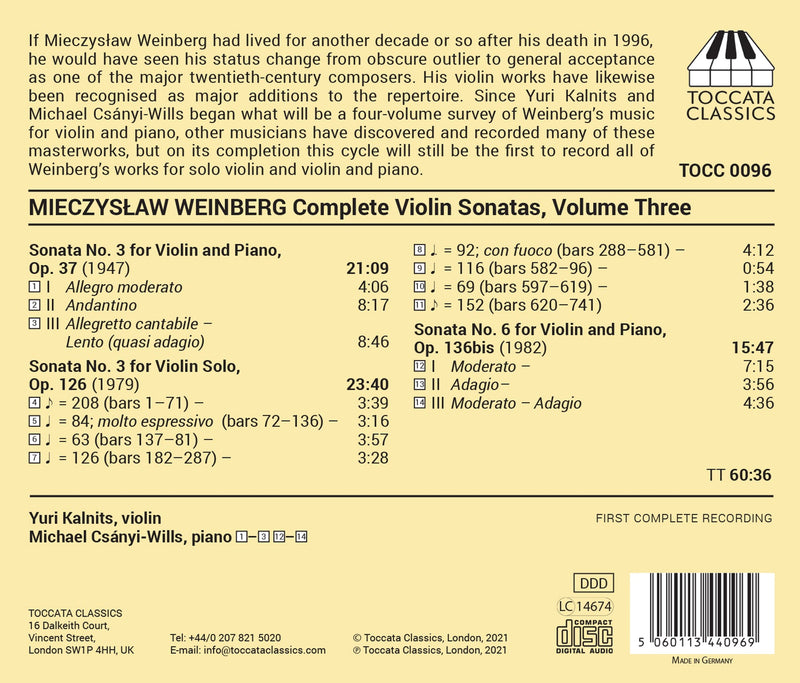

On SaleToccata

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

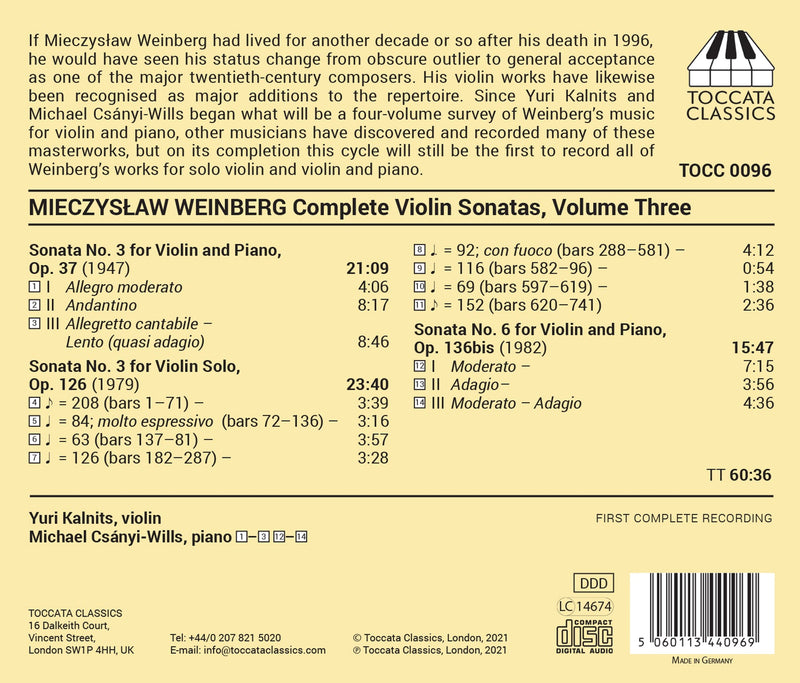

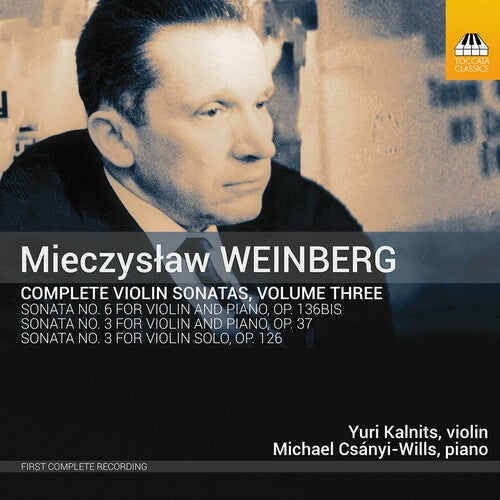

On SaleToccataWeinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas, Vol. 3 / Csányi-Wills, Kalnits

If Mieczyslaw Weinberg had lived for another decade or so after his death in 1996, he would have seen his status change...

March 05, 2021$20.99$15.99 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

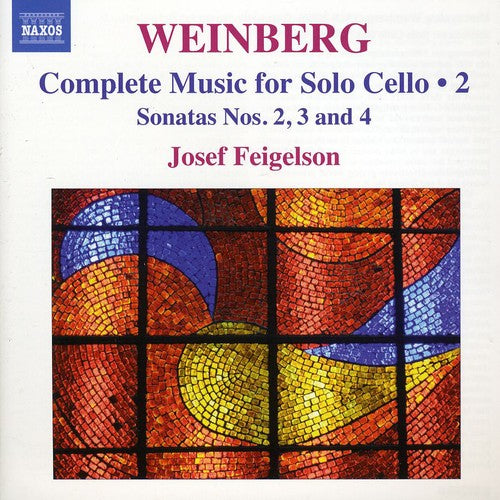

Naxos

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

NaxosWeinberg: Complete Music For Solo Cello Vol 2 / Josef Feigelson

Emotional Soviet solo cello. If that’s what you’re looking for, this is hard to beat. Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s solo cello sonatas are considerably...

$19.99January 25, 2011 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleNaxos

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

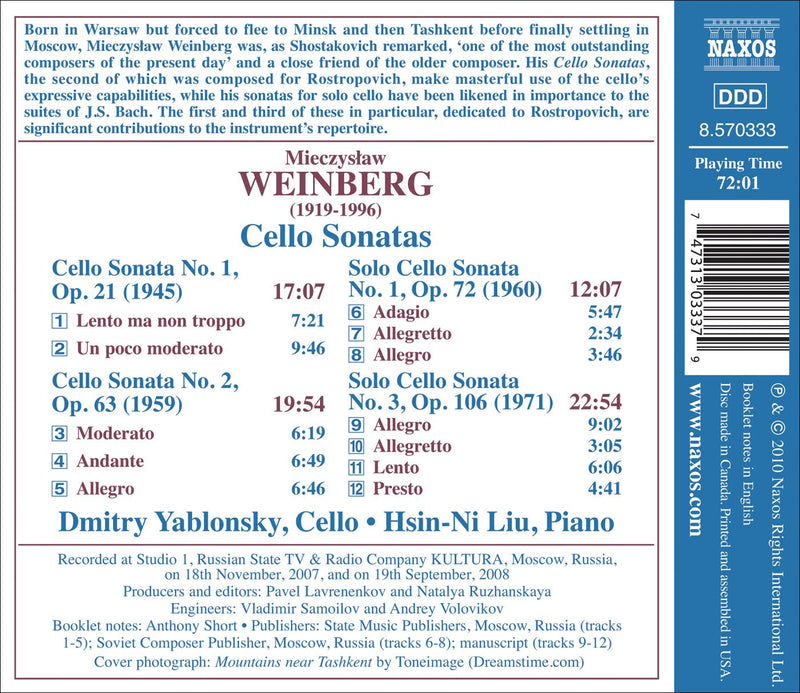

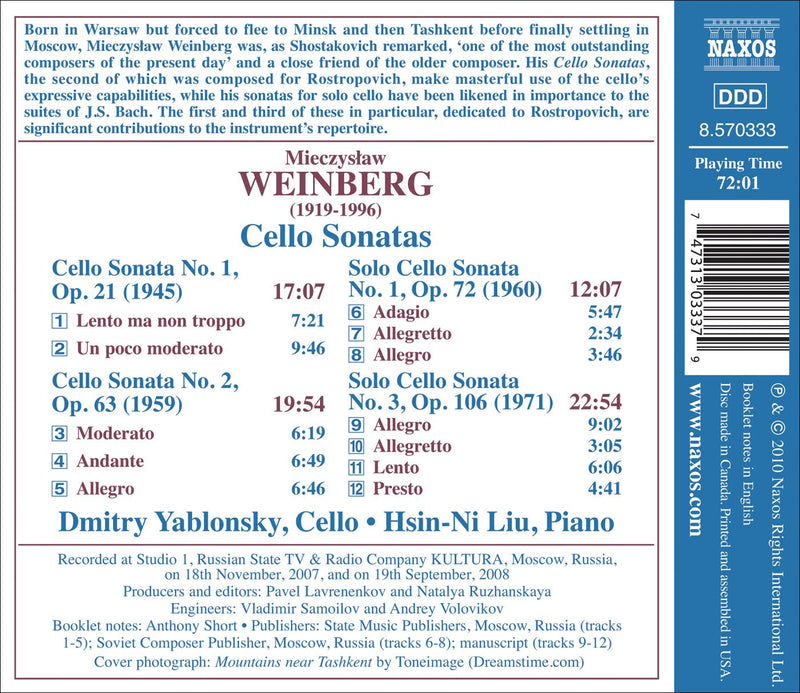

On SaleNaxosWeinberg: Cello Sonatas / Yablonsky, Liu

.Born in Warsaw but forced to flee to Minsk and then Tashkent before finally settling in Moscow, Mieczyslaw Weinberg was, as Shostakovich...

March 30, 2010$19.99$9.99 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Divine Art

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Divine ArtRussian Piano Music Series Vol 10 - Weinberg / Murray Mclachlan

Mieczyslav Weinberg (aka Moisey Vainberg) was in fact born and raised in Poland, but the vast majority of his compositional career was...

$19.99August 06, 2012 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Toccata

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

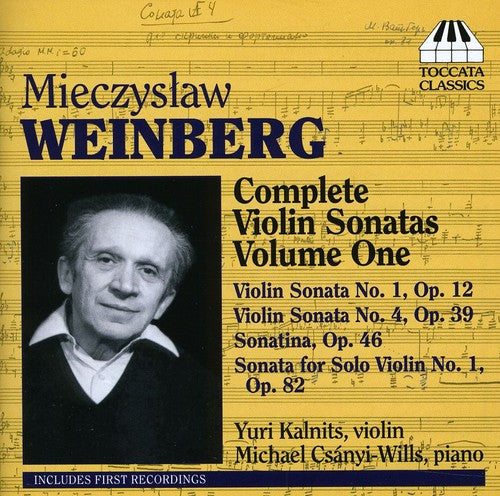

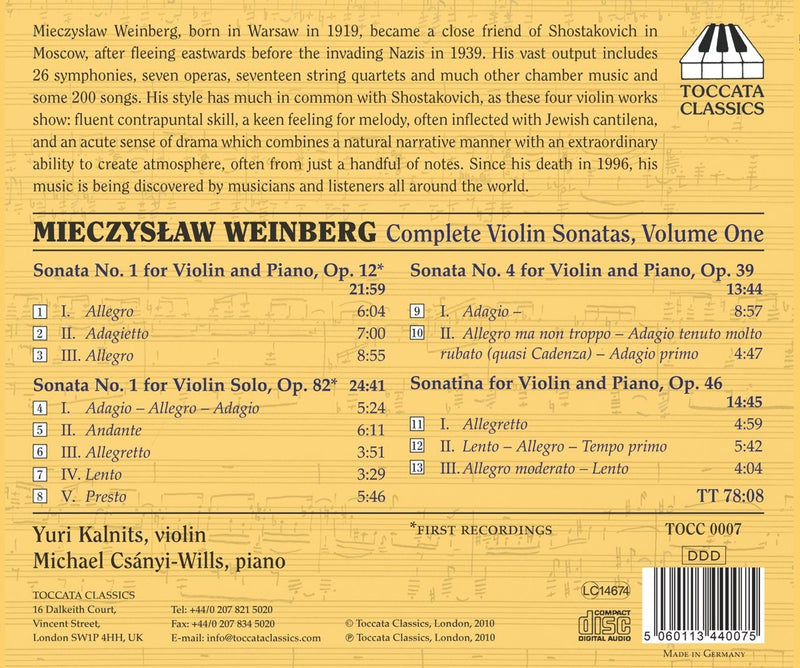

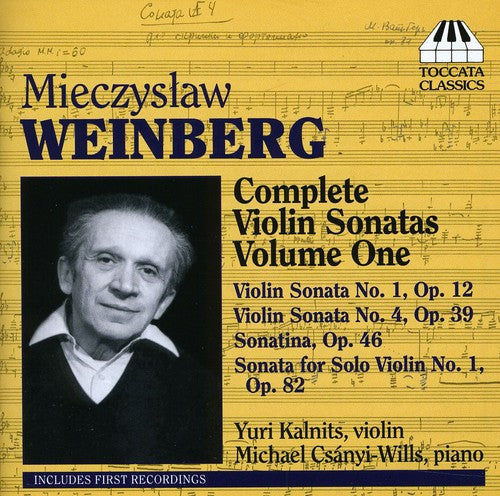

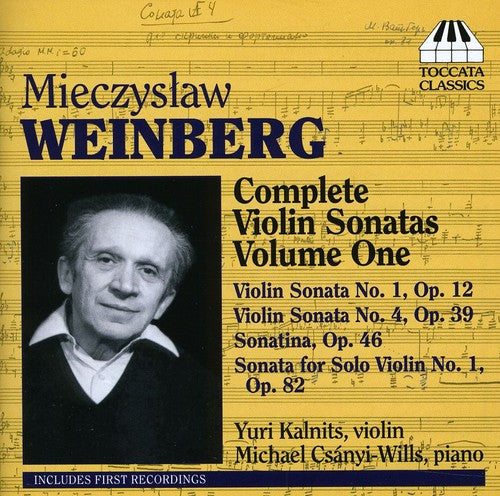

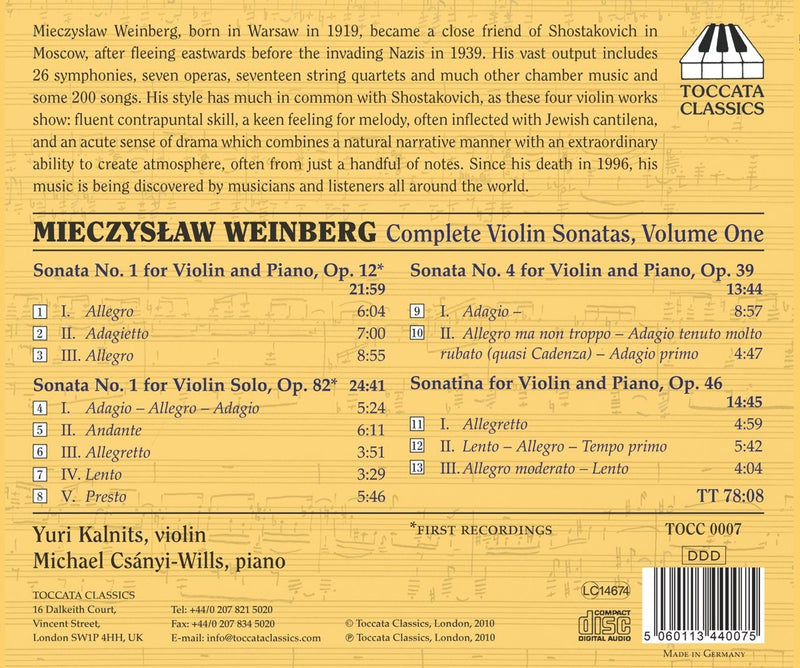

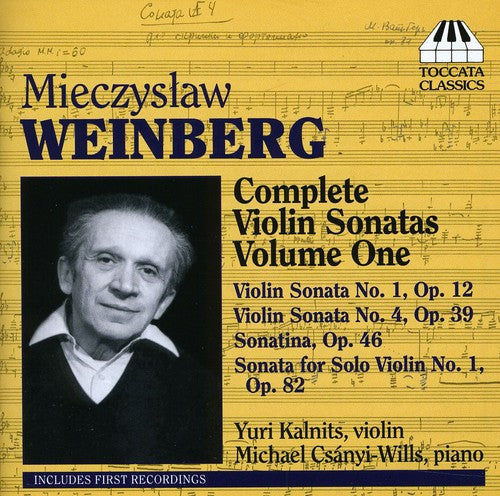

ToccataWeinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas, Vol. 1

WEINBERG Solo Violin Sonata No. 1. Violin Sonatas: No. 1; No. 4. Sonatina • Yuri Kalnits (vn); Michael Csányi-Wills (pn) • TOCCATA...

$20.99February 08, 2011 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Toccata

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

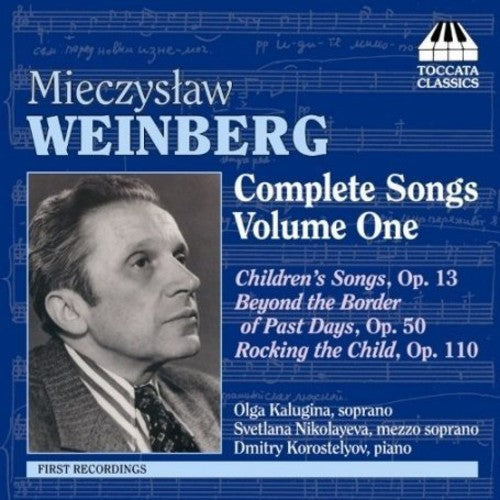

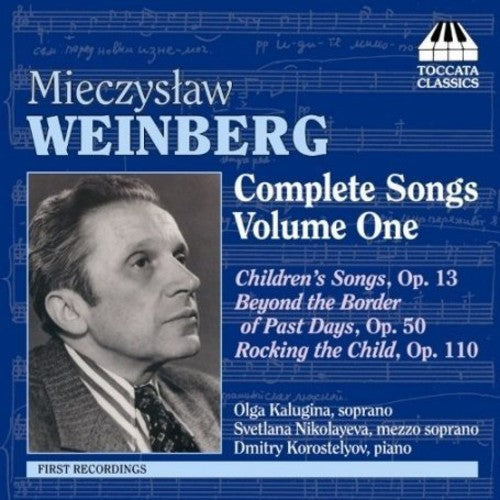

ToccataMieczyslaw Weinberg - Complete Songs, Vol. 1 / Kalugina, Nikolayeva, Korostelyov

WEINBERG Children’s Songs. Beyond the Border of Past Days. Rocking the Child • Olga Kalugina (sop); Svetlana Nikolayeve (mez); Dmitri Korostelyov (pn)...

$20.99October 14, 2008 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Naxos

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

NaxosMieczyslaw Weinberg: Complete Music For Solo Cello, Vol. 1

The importance of Mieczysław Weinberg’s 24 Preludes for solo cello, written for Rostropovich, lies beyond their superficial resemblance to Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier...

$19.99December 14, 2010

Weinberg: Complete Piano Works, Vol. 3

Weinberg: Complete Piano Works, Vol. 4

Weinberg: Cello Concerto, Op. 43; Fantasy, Op. 52 & Concertino Op. 43bis / Borowicz, Kristiansand Symphony

Mieczyslaw Weinberg grew up in Warsaw, a city in which Poles then accounted for two thirds of the populace and Jews for one third of its residents. The Jews increasingly regarded themselves as Poles, just as he did. The three works on this album clearly attest to the fact that Weinberg felt that he belonged to both traditions. The Concertino and the Cello Concerto have Jewish roots, while the Fantasy is a piece with a typically Polish character. If the Concertino, in which the orchestra is extraordinarily sparingly used and the violoncello practically plays a solo, may be described as the composer’s »lyrical journal« in music notes, then the Cello Concerto derived from it has even more clearly been written for the grand stage. It is more fully developed, the work has assumed a new character, and the orchestra plays a more important role in it. These changes are apparent already in the first movement and become more and more clearly audible in the following movements. A new theme is sounded in the second movement, and the wind instruments imitate the sound of klezmer groups. The third movement assumes a central significance and verges on a bravura piece without ever losing its popular character practically suggesting folk music. The soloist’s cadenza, here very much more clearly structured than in the Concertino, leads to the finale, which creates the impression of having been added to lend the music the prescribed “Soviet optimism.” However, when the theme from the first movement returns at the very end, this initially occurs with an admixture of pathos, then somewhat sentimentally – which situates this work very far from the intimate music familiar to us from the Concertino.

Weinberg: Piano Sonatas Opp. 8, 49bis & 56 / Blumina

The Echo Klassik prizewinner Elisaveta Blumina numbers among the outstanding female musicians of the younger generation who pursue their own paths, unaffected by any sort of “star cult.” Along with the classical piano repertoire, Elisaveta Blumina occupies herself very intensively with the music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Her internationally highly regarded recordings of the Soviet Jewish composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg, to whose rediscovery she is tirelessly committed, are among the projects documenting this involvement. For cpo she has now recorded three sonatas by Weinberg. The clear proportions and modest length of the Sonatina op. 49 led Weinberg to rework it in 1978 in order to expand its structure, lengthen it into the Sonata op. 49, and to readjust its balance. In this sonata of classical design Weinberg further developed the spectrum of musical expression and increased the technical demands when compared to his Sonata No. 2 and the Sonatina. The Sonata op. 49 numbers among the few productions for the concert hall from this creative phase, which was reserved for intensive occupation with film music – and in particular for animated films. Emil Gilels recorded the Sonata No. 4 in 1960. Unlike the version by this dedicatee, which maintains a swift tempo, Elisaveta Blumina’s slower, more intensive playing lends greater expression to the work’s drama and grief.

Weinberg: Works for Violin & Piano, Vol. 2 / Kirpal

This is the second volume of Mieczyslaw Weinberg's works for violin and piano. Weinberg's Violin Sonata No. 1 covers the path from C minor to C major, a popular tradition of the time while Sonata No. 2 reveals his increasing creative ambitions. Sonata No. 3, has a lyrical tone which dominates the first movement. The structural design is more economical and grows more elaborately throughout.

Weinberg: Piano Trio; Violin Sonatina; Double Bass Sonata

WEINBERG Piano Trio. 1,2,4 Sonatina for Violin and Piano. 1,3 Sonata for Solo Bass 5 • 1 Elisaveta Blumina (pn); 2 Kolja Blacher (vn); 3 Erez Ofer (vn); 4 Johannes Moser (vc); 5 Nabil Shehata (db) • CPO 777804-2 (68:23)

The music of Mieczys?aw Weinberg continues to be issued, and continues to impress. Like his British counterpart, York Bowen, Weinberg was a composer trapped in time and place, and it is good that their very different musics are now coming to the fore with such regularity. One of the wonderful things about this disc, aside from the committed, intense playing of the instrumentalists, is the sound: crisp and clear, with only a very little reverb, which brings the sound of the instruments into sharp focus and makes the listener pay attention to the music.

Like Bowen, Weinberg was largely a tonal composer, although heavily influenced by Bartók and his personal friend Shostakovich. Unlike Shostakovich, however, Weinberg seldom engaged in whining, overwrought musical breast-beating; his aesthetic was geared at bringing out intense personal feelings, but always with good taste and a less mocking or posturing tone. The piano trio that opens this disc is a perfect example. Weinberg immediately grabs our attention with a strident forte tremolo on the violin, and this sets the pace for the musical marvels that follow. The intensity of this piece was inspired, so the notes suggest, by Weinberg’s sight of Polish mothers with their children hugging the legs of Russian horses, begging the Soviet soldiers to let them come over because the Nazis were after them. It was that horrible, that terrifying, and the first movement of this trio reflects that mood. So, too, does the raw power of the ensuing Toccata, which builds up to a powerful fugue; and even the slow movement (“Poem”), which begins softly, still has an undercurrent of menace and unrest, which breaks out in the middle of the movement into an ostinato piano figure, receding in volume and intensity to a quiet, almost submissive ending with the violin playing soft, muted passages. The finale does not toy with a fugue, as did the second movement, but builds up through its quiet opening into a really complex and powerful fugue—oddly enough, based on entirely different thematic material from the opening, which sounds like a Bachian fugue theme. This is clearly one of Weinberg’s masterpieces.

Where do we go from here? To the sonatina for violin and piano from 1946, a piece that sounds like the diametric opposite of the trio. Set primarily in D Minor, but vacillating in and out of F major, the sonatina has touches of melancholy about it, but is primarily a lyrical work with what may be termed episodes of sadness. Here, too, some of the melancholy passages sound related to Jewish folk music without ever really using genuine themes. But ever and anon, Weinberg holds your interest through his amazingly creative sense of construction (would that many of our modern-day American wunderkind composers listen to his work and pay heed to what he does). Nothing in Weinberg’s work is ever flippant, thoughtless, or peripheral; he thinks in terms of the whole picture without sacrificing the detail of internal episodes.

One should be forgiven for thinking in advance that to end this disc with a solo sonata for the rather lugubrious-sounding double bass would be a bit of a downer; after all, solo bass sonatas don’t exactly grow on trees. Yet, after an almost predictably slow first movement, Weinberg becomes much more involved in writing music and not necessarily just writing for the bass, if you know what I mean. His creative forces flowed in one direction, which was towards the creation of fascinating musical forms, and never towards empty virtuosity or just “filling space” with his music. Thus the potential interpreter needs to stay focused not so much on the technical challenges (and there are many in this sonata) as on the musical progression and what it means in terms of expressive content. (I fond it interesting, in the notes, to read that bassist Shehata thinks of it as more “similar to a suite in which each movement is structured very clearly thematically.”) I also noted that, aside from its musical marvels, Weinberg manages to elicit some very interesting sounds from the bass, including percussive effects that almost make it resound like an organ—or, in the last movement, pushing it up into the cello range.

The playing of each musician on this disc, from pianist-director Blumina to double bassist Shehata, is simply astonishing, so deeply rooted in the music that it seems to be an extension of the notes on the page, not an extension of a virtuoso who says to the listener, “Look at me, I’m wonderful!” It is virtuosity that consistently serves the composer and his message, not the ego of the performer. This is a truly great disc.

FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Weinberg: Complete String Quartets / Danel Quartet

WEINBERG String Quartets Nos. 1–17. Capriccio. Aria • Qrt Danel • CPO 777913 (6 CDs: 436:41)

If you’ve not been collecting CPO’s Weinberg string quartet cycle with the Danel Quartet, here’s your chance to acquire it complete—all 17 quartets—in a boxed set, selling for under $8 per disc at ArkivMusic. It’s not as if there’s a lot of competition, either. The Pacifica Quartet included Weinberg’s Sixth Quartet in Volume 3 of its complete Shostakovich quartet cycle. There’s a single Delos CD of Weinberg’s quartets 11 and 13, performed by the Vilnius String Quartet; one surviving Olympia CD containing the quartets 7, 8, and 9, played by a group calling itself the Dominant Quartet; and a No. 8 recorded by the Borodin String Quartet for Melodiya. And that, to the best of my knowledge, is about it, at least insofar as what’s currently available on CD. I don’t know if a complete Weinberg quartet cycle was ever undertaken in the LP era.

Mieczys?aw Weinberg (1919–1996) has long stood in the eclipsing shadow of his close contemporary and loyal friend Shostakovich. But Weinberg’s neglect is not entirely due to his being judged the lesser of the two composers; much of it is due to his being charged, and not entirely without good reason, as being a shameless Shostakovich imitator.

Anyone who is familiar with Shostakovich’s 15 string quartets and who listens to Weinberg’s quartets can’t entirely deny the accusation, for there is at least a kernel of truth to it. One hears many of the same techniques—the lengthy and sometimes fierce rhythmic ostinatos, the corrosive dissonances, and the hollow, haunted-sounding melodies—as well as many of the same emotional states—the feeling of bone-chilling cold, the sense of caustic, cruel irony, and a palpable perception that perpetual tragedy is life’s natural condition.

Certainly the Jewish Weinberg had even more cause for such a bleak outlook than Shostakovich did. Born in a Warsaw ghetto, Weinberg was the only member of his immediate family to survive the Holocaust, and but for Shostakovich’s intervention and Stalin’s sudden death, he almost didn’t survive a Soviet purge of Jews in 1953 that came to be known as the “Doctors’ Plot.”

Before receiving this six-disc set, I was familiar with only two or three of Weinberg’s quartets, and I can tell you that now, after listening to all of them, my previous skepticism has been transformed into genuine enthusiasm. The first thing I learned is that the “Jewish” element is more pronounced and more pervasive in Weinberg’s music than it is in Shostakovich’s, no doubt an artifact of his childhood years in a family of itinerant Yiddish theater performers.

The second thing I discovered was that there is an underlying lyrical lilt to much of Weinberg’s writing, especially in the earlier quartets, that doesn’t sound all that strongly influenced by Shostakovich. The Fourth Quartet, for example, composed in 1945, after Weinberg had already been in the Soviet Union for several years and had already struck up his relationship with Shostakovich, is a real melodic beauty.

Only Weinberg’s First Quartet, dating from 1937, was written in Poland, two years before the composer fled the country ahead of the Nazi invasion; and it was one of only two of his 17 quartets he would later revise. It’s the revised version, made almost 50 years later in 1986, that’s performed here by the Danel Quartet, the original being practically illegible in many parts, according to the album note.

The Second Quartet, dating from 1940 and composed shortly after Weinberg had arrived in Minsk, was also extensively revised almost 50 years later in 1987, but that revision, bearing a different opus number, was rescored as a chamber symphony, so that the quartet stands as an independent work.

After that, Weinberg’s output of string quartets remains pretty steady up until 1987. He wrote no more quartets in the last nine years or so of his life, but he did write a 20th Symphony, three more chamber symphonies, a flute concerto, and most curiously, a “Kaddish” Symphony, his penultimate work—curiously, because it’s reported that just two months before his death in Moscow, he converted to Orthodox Christianity.

The quartets are arranged in the order they were originally released on the individual CPO discs, which means they’re not ordered chronologically, skipping randomly from one to another. The First Quartet doesn’t show up until Volume 5, while the second to the last quartet, No. 16, is on Volume 1. But if you purchase this set, I strongly suggest that you listen to the cycle in numeric/chronological order, because that way it becomes easy to hear Weinberg’s writing before he fell so profoundly under Shostakovich’s influence, during the period of that influence, and after it. The last five of Weinberg’s quartets were, in fact, composed between 1977 and 1987, post-Shostakovich’s death in 1975.

By listening to the quartets in this way, one hears the many different influences that Weinberg was subject to. In the first two or three quartets, there’s a strong sense of Berg and the music of the Second Viennese School, as well as of Bartók, which Weinberg would probably have been exposed to during his studies at the Warsaw Conservatory. Then we encounter the Shostakovich influence from about quartets Nos. 5 or 6 through 12. But along the way, Weinberg had to have encountered Prokofiev and Myaskovsky too. The last five quartets, Nos. 13 through 17, largely continue in the vein of Weinberg’s now deceased mentor, Shostakovich, but more Modernist elements of other Soviet composers active at the time, for example, Alfred Schnittke, begin to creep into Weinberg’s writing.

I realize that all of these discs have been (and still are) available individually; these are not brand new releases, but presented here as a complete cycle, I believe this set represents an important milestone in the Weinberg revival, and it affords us a fuller perspective on this neglected Soviet-era composer. These quartets make for really interesting and, for the most part, really rewarding listening.

The Danel Quartet, which already recorded a complete Shostakovich cycle for Fuga Libera and a number of other works by mostly 20th-century French composers, is truly superb, and CPO’s recordings are clear, bright, and perfectly balanced. This is very strongly recommended to anyone interested in becoming acquainted with a major body of 20th-century string quartet music.

FANFARE: Jerry Dubins

------

WEINBERG String Quartets Nos. 1–17. Capriccio. Aria • Qrt Danel • CPO 777913 (6 CDs: 436:41)

Initially released as individual discs between 2007 and 2012, this set of Weinberg’s 17 quartets plus the capriccio and aria seems to have flown, by and large, under the critical radar. I could only find a few reviews online: Vol. 1 by Steve Schwartz at Classical Net, Vols. 1 and 3 by Barry Brenesal here in Fanfare, Vol. 5 by Gary Higginson at MusicWeb International, and Vols. 1, 4, and 6 at allmusic.com, although Quatuor Danel’s complete set of the Shostakovich quartets on Fuga Libera garnered high praise from James Leonard at the latter web site.

As is so often the case with sets of complete quartets or symphonies, the works are presented well out of order. Vol. 1 contains quartets Nos. 4 and 16; Vol. 2 quartets Nos. 7, 11, and 13; Vol. 3 quartets 6, 8, and 15; Vol. 4 quartets 5, 9, and 14; Vol. 5 quartets Nos. 1, 3, and 10 (along with the capriccio and aria); and Vol. 6 quartets 2, 12, and 17. I wish I had a window into the heads of record producers, and thus had some idea to give you as to why we get these things in such a crazy-quilt pattern. It would be one thing, I believe, if they had only recorded six or nine of the 17 quartets. In that case, you might expect that they’d be programmed for contrast’s sake and not chronologically, but when you get a complete set of 17 works written over a long span of time and in differing styles, I really appreciate being able to hear them in the order of composition so as to get a hold on the composer’s mindset and growth as an artist.

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, all I can say about this music—individually per quartet and as a whole—is that it is simply astonishing that this poor guy was ignored for so many decades. The reason, one fathoms from reading his biography, was not as mysterious as it may seem considering the exceptionally high quality of his work. As a Polish-Jewish refugee who fled to the Soviet Union to get away from the Nazis, only to find that he was now persecuted by his new country, he refused to become a member of the Communist Party and thus worked almost completely outside the system. His good friend Shostakovich had to send a letter to the head of the secret police to save Weinberg’s skin at one point, so the composer was never executed or sent to a Gulag, but he didn’t have an easy life; and, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, he was so little known except by a few musicians who were friends and confidantes of Shostakovich that he was still pretty much ignored even within the New Russia.

Since the opening disc pairs an early quartet and his last one, we come to appreciate his stylistic differences between the early and late Weinberg. In a nutshell, he was able to internalize much of his angst as he grew older and reflect on what had passed in a way that was less emotionally intense but no less personally meaningful. Thus in the Quartet No. 4 (op. 20), we hear a Weinberg who is still very strongly and emotionally scarred by the brutalities of the Nazi regime which he fled (similar angst maybe heard in his piano trio, which I review elsewhere in this issue), while the last quartet, dedicated to his sister Ester, who died in the camps, is more quiet and reflective if no less deeply felt. Structurally, however, it is the most conventional of all his works I have yet heard. The really fascinating thing about Weinberg in general is that no matter what the emotional stimulus of any given work, he was able to transform it into a musical statement that could be felt by others, his personal grief and angst thus becoming more universal in its message. In this respect, and in these particular works, Weinberg was Beethoven’s spiritual successor. One can very easily move from the late Beethoven quartets to Weinberg’s with no loss in musical interest and certainly no loss in emotional impact.

Curiously, the Quartet No. 7 that opens Vol. 2 is also a relatively quiet work, as the composer was apparently trying to placate the hostile Soviet authorities (his Quartet No. 6 was banned for a time by Stalin, though ironically, at another time, his music was praised by the Soviets “for depicting the shining, free working life of the Jewish people in the land of Socialism”). In terms of musical construction, however, it is less formal or conventional than the last quartet, the sustained invention of the work continually fascinating despite the low-key dynamics and often muted strings, though the music virtually explodes in the last movement.

The 11th Quartet (1966) is played almost entirely muted, with only large sections of the Adagio semplice (third movement) unmuted, played by individual members of the quartet as solos. This was yet another example of Weinberg’s originality of design, yet as usual with this composer one should not put too much stress on the structure; it is the musical progression, and the stories his music tells, that are one’s primary focus. Indeed, aside from the effects just noted, the overriding feeling one gets from this quartet is of an almost perpetual motion. One must praise the members of Quatuor Danel for their ability to play in different styles and moods throughout these quartets. In addition to the unusual string of solos in Quartet No. 11, Weinberg sometimes wrote for the strings to play off one another and sometimes to play as a unified group, and the unusual shape and textures of his music with its unusually varied attacks (not to mention extraordinarily fine shadings of dynamics, which are in constant flux from moment to moment) are not easy to play properly. I’m sure that many, many hours of rehearsal time went into these pieces.

The one-movement 13th Quartet, written shortly after the death of Shostakovich, is a structurally broken work in which, as the notes say, the “scherzo, slow movement and finale sections are weakly articulated and blurred by references back to the opening theme and by developmental recombination of ideas.” In terms of mood, however, Weinberg seems as upset about the unjust persecution his friend suffered as he was sad about his passing, as there are several angry-sounding passages in it, and its generally consonant harmonic base is at times disrupted by tense, edgy tone clusters.

Vol. 3 opens with the Quartet No. 6 from 1946, the one banned by Andrey Zhdanov for formalism. Although it bears Weinberg’s unmistakable stamp, particularly in his varied use of the strings at different points throughout the work, in melodic and harmonic terms it sounds, to me, the closest to Shostakovich. Still, one is constantly kept on one’s toes by its constant shifting of mood and rhythm (perhaps Zhdanov banned it because he couldn’t follow it!). I was particularly struck by the third movement, Allegro con fuoco, with its almost ferocious use of pizzicato effects, as well as by the canon used in the fourth movement ( Adagio ).

The Quartet No. 8, from 1959, is a one-movement work, but this time with three clear-cut sections to subdivide it. Despite this nod to conventional form, however, it is still music by Weinberg, which means that it is fascinating and diverse in its use of themes and development. Among these are his use of “sighing figures,” as the notes describe them, overlaid on the C-Major triad in the first movement, and the rondo-like Allegretto which forms itself into a second movement, with klezmer-like intonations used underneath. Occasionally, Weinberg strikes up a regular rhythm, but then slowly increases its pace until it becomes a sort of “whirling dervish” dance, with the string attacks becoming more intense as it changes from a dance to an insistent, driving rhythm. He solves his own musical puzzle, at last, by combining the opening section’s Adagio with a new phrase in which earlier themes are thrown into the musical blender with it, eventually putting its varied parts together.

The 15th Quartet (1980) is one of his strangest and most original, split into nine movements with metronome markings but no titles or expressive directions. Once again Weinberg uses mutes on the strings, in this case producing a murmuring, undulating effect that keeps trying to coalesce into a theme but never quite makes it. The music has an elusive quality, like trying to grab a handful of mist; you come close but never quite succeed in your quest. Here is a musical story told by allusion and innuendo, with nothing stated clearly and very little in the way of signposts for the listener to hold onto—at least, not until the surprisingly vivid, violent fourth movement, where the mutes are finally removed and the attacks are ferocious. From this point, the next three movements retain a constant level of loudness, even through a canon played by the two violins in minor seconds, eventually intruded upon by the other instruments as the music deconstructs. More than a vague hint of Beethoven is heard in the sixth movement as a snippet of the opening theme of one of his “Razumovsky” Quartets is tossed around between the strings. Weinberg brings back the mutes for the eight movement, a Bartók-like piece played in pizzicato, with ambiguous melodies again trying to form themselves. Eventually we reach the ninth and final movement, in which a sad, lyrical, yet broken melody again fails to coalesce.

Vol. 4 opens with Quartet No. 5 (1945), the opening tune of which—playing by solo violin—is one of the loveliest things Weinberg ever wrote, a piece he could easily have turned into a song. Indeed, even after the other instruments enter, one at a time, he continues to develop and evolve this gorgeous melody to almost Bellinian or Wagnerian proportions (tune-wise, not in terms of Wagnerian texture). Moreover, as the melody continues to morph, it becomes even more eloquent and touching. Here, again, we have a different approach from Weinberg, yet he is able to convince us, for the duration of this quartet, that it is right and meaningful. The second movement “Humoreska” is, for once, really a humorous tune, ambling along in its quirky, syncopated way like a tipsy hobo who thinks he’s walking a straight line but isn’t. In the development section of this movement, Weinberg ejects the syncopations and turns the melody into a more lyrical tune played by second violin and viola, while the first violin plays odd pizzicato figures above it; then, returning to the syncopations (now played by viola), the other three instruments lightly embroider its melody with pizzicato of their own. After a similarly wacky scherzo and an ethereal slow movement “Improvisation,” the quartet ends with a “Serenata” that sounds a bit like Haydn, or at least Prokofiev in a Haydnesque mood.

The Ninth Quartet (1963) reveals Weinberg attempting a slightly different format. The work is divided into four discrete movements, marked Allegro–attacca, Allegretto–attacca, Andante–attacca, and Allegro moderato . Moreover, he seems to have taken up the task of reinventing the “Classical” model of a quartet, its extremely dense and complex sonata form repeating both expositions and development sections. Rhythmically, this quartet follows more standard Classical rhythms, almost Stravinskian in their rigor and stiffness, the harmony often bitonal and constantly shifting sideways in and out of different keys. By this time one will have noted that one of Weinberg’s traits is to let the listener expect certain things, but then to pull the rug out from underneath. Themes are sometimes juxtaposed in strange and quirky ways, there are inspired leaps into strange realms, yet in the end he always seems able to pull it all together.

Quartet No. 14 (1978) is another of those with only metronome markings, no movement descriptions, and a furtive, almost mysterious method of composition and mood. The first movement’s almost ostinato rhythm tends towards Minimalism, at that time pretty much a new style, but Weinberg wasn’t interested in endless repetition of short thematic fragments. Here the intensity of his expression almost sounds like a howl of despair or anger, or both. There is also angst (and sorrow) in the slow movement, which almost sounds tonally based at first but soon veers off into strange harmonic territory. The third movement has a scherzo-like rhythm, but is subdued in mood and, again, sounds almost fragmented in its direction but is really quite well constructed. The slower fourth movement is also melancholy and despondent. The fifth and last movement seems to coalesce its musical materials more concisely, but eventually shifts feeling and focus, ending quietly—as the booklet says, “in unresolved thematic oppositions, tinged with fragile harmonics … and in a final inscrutable, white-note cadence.”

The opening of Weinberg’s very first quartet (Vol. 5), written in 1937 but revised in 1985, opens in such a way that it sounds as if you are already in the middle of the movement (a bit like the opening of the Mahler Sixth Symphony, only much quieter). Because the years of its initial composition and revision were so far apart, Weinberg assigned the quartet two opus numbers (2 and 141). The booklet explains that Weinberg left the quartet’s formal design and harmonies intact, but in 1985 was “recasting and clarifying the texture.” Even if you consider both this later maturity of texture and that some passages may indeed have been changed, this product of the 18-year-old composer is already a mature work, interesting and involving to hear. Although the notes throughout this series persistently compare Weinberg’s quartets to those of Shostakovich—a comparison I find unfair to both composers—for this one the annotator instead mentions its resemblance to some of Bartók’s and Szymanowski’s music. I, however, hear no real stylistic difference between this quartet and the later ones other than Weinberg’s own maturity and willingness to explore different forms of construction. In other words, I felt all along that Bartók was his real model, and the constant comparisons with Shostakovich are superficial and peripheral. Thus I hear some elements of Bartók not only in this First Quartet, but also in the Third Quartet which follows on this disc, although the Third is a bit more assertive. Weinberg was, simply, an excellent composer from about age 18 onward, and although he himself dismissed some of his early works in later life, there are some really fine pieces in his early oeuvre, as the early Aria (op. 9) and Capriccio (op. 11) that close this disc illustrate.

Between the First Quartet and these shorter pieces, however, is the Third Quartet (1944), and it is much the same as the Quartet No. 4 which followed, and if a shade less angst-ridden still on the “edgy” side. It’s a shame that so many younger listeners of “classical” music nowadays want soft, relaxing music, something to sip wine to and slip into a semiconscious state—“Mellow with Mozart” or “Zone Out with Zemlinsky.” Yes, that is certainly part of what classical music is about, too, but the music is also designed to project edgier, more intense emotions, and I for one can’t really imagine modern-day “nocturnivores” (as they describe themselves in a fast-food chain’s radio advertising) listening to many of these Weinberg quartets. What a pity.

The Tenth Quartet (1964) divides its four movements up into slow-fast-slow-fast, but once again Weinberg treats the whole quartet as if it were one continuous movement with different moods. The cello employs an unusually strong vibrato to lead into the first movement, but note here, again, how Weinberg leads the listener into thinking this opening melodic statement will develop into a broad, half-tone melody before breaking it up with strong accents on each of the four beats for several measures. As usual with this composer, the music continues to morph in its progression, becoming ever more melancholy as it simplifies the rhythm and indeed does become a succession of half notes, then whole notes. The second movement, with its broken, asymmetric rhythm, sort of sneaks up on the listener, in part because it is played softly with muted strings (another Weinberg trademark). By contrast to this scherzo, the third movement Adagio is played loudly and passionately on open strings—yet another twist for the listener. A long-held D? on the cello eventually morphs into the last movement’s opening, again quiet and almost calm in mood, but a semi-lively syncopated rhythm is set up which then leads into other themes, including a somewhat simple waltz, before winding its way in roundabout fashion to another cryptic finale, another tale told via allusion and musical metaphor. The early capriccio is, to my ears, very strongly influenced by Prokofiev’s “Classical” Symphony, the aria influenced by—Gabriel Fauré? That’s what it sounded like to me, and I was happy that the liner notes agreed with my assessment.

CD 6 begins with Quartet No. 2, another piece (like Quartet No. 1) that he revised much later in life, thus it bears the dual opus number of 3/145. Once again, I hear in this earlier work a lot of Prokofiev in his tongue-in-cheek Neoclassical style, but again filtered through Weinberg’s extraordinarily inventive mind. It almost boggles the imagination that, as Alex Ross put it in one of his New Yorker articles, Weinberg thought very little of his music and even gave up on getting his works published, let alone performed, during the last decade or more of his life. In the liner notes by Elisaveta Blumina for the CPO disc of Weinberg chamber works (reviewed elsewhere in this issue), the pianist mentions that his one claim to fame within Russia was that he wrote the music for Winnie the Pooh cartoons! (In fact, you can find some of those Russian Winnie cartoons from the late 1960s-early 70s on YouTube with Weinberg’s music in them.) It’s a bit like imagining a major figure such as Stravinsky giving up on himself, writing background music for George of the Jungle cartoons, then later not caring if his music was published or performed. I found this Second Quartet to be one of Weinberg’s lightest and wittiest; one might be forgiven for thinking it was written before the Nazi horrors, but in fact it was composed between November 1939 and March 1940, the period during which he abandoned Poland (where his mother and sister were murdered) for Belarus.

The 13th Quartet (1969–70) is very much in the Bartók mold, even though the opening section smacks of serial music (and, in fact, the notes point out that these bars are “loosely based on a 12-tone aggregate”). It’s not so much an angry or angst-ridden quartet as it is one informed by a great deal of internal pain and confusion. To me, this music seems to say, “Why am I so alone? Why is no one on my side?” Believe me, I can relate. As usual, Weinberg never resorts to cheap effects, to heart-on-the-sleeve weeping. All of the emotions are internalized, all of his pain transformed into quiet yet meaningful musical statements. And, believe it or not, this quartet just gets stranger and stranger as it goes along, until you feel that Weinberg has completely wrapped himself up in his own private musical cocoon.

The 17th and last Quartet, ironically, returns us to the more playful, carefree Weinberg of his youth. Written in 1986 for the Borodin Quartet’s 40th anniversary, it is a joyful piece, quite different from the sad lament of the Quartet No. 16. Weinberg, at least quartet-wise, thus leaves us not with a bang or a whimper but with a smile.

At first, the recorded sound of this set didn’t seem to me as clear and crisp as the Blumina disc (CPO 777804), but as the music progressed I was pleased to discover that one could still hear the bite of the strings and that the visceral impact of this music was not dulled by mushy, gooshy sonics. This is, quite simply, a great set.

FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Weinberg: Piano Quintet (Orchestral Version) - Children's Notebooks, Books 1 & 2 / Elisaveta Blumina, Ingolstadt Georgian Chamber Orchestra

Five years after Shostakovich premiered his quintet to turbulent success in 1940, his new 24-years young friend Weinberg premiered one of his own. For the premiere on March 18th, the 27-year old Weinberg got the String Quartet of the Bolshoi and a 30-year old pianist, already famous then, by the name of Emil Gilels. The Quintet op.18 is one of the unequivocally great chamber pieces of that time and it is a superb entry-point into the world of Weinberg. As with any truly great masterpiece, a work like the Piano Quintet benefits and indeed demands many and diverging interpretations. This also includes different versions, such as this arrangement of the quintet for chamber ensemble. The idea is hardly far-fetched: Weinberg arranged several of his own works for chamber orchestra; his friend Shostakovich’s string quartets have popularly lent themselves to such arrangements. It suits the treatment naturally – and the orchestral version, therefore, gives us just one more way to discover and enjoy one of Weinberg’s ingenious gifts to his belated but finally eager public.

Weinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas, Vol. 3 / Csányi-Wills, Kalnits

If Mieczyslaw Weinberg had lived for another decade or so after his death in 1996, he would have seen his status change from poorly known outlier to general acceptance as one of the major twentieth-century composers. His violin works have likewise been recognized as major additions to the repertoire. Since Yuri Kalnits and Michael Csányi-Wills began what will be a four-volume survey of Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s music for violin and piano, other musicians have discovered and recorded many of these masterworks, but on its completion this cycle will still be the first to record all of Weinberg’s works for solo violin and violin and piano.

REVIEW:

The most ingratiating music comes right at the start, with the first movement Allegro moderato of the Violin Sonata No.3 from 1947. Its four minutes begin with a lyrical theme of varying phrase lengths which the players keep flowing as it were “in one breath”. The fugato style second subject is a perkier counterweight and the sonata form progression is coherently delivered, and the lowish emotional temperature feels just right as there are two movements each twice the length of this one to come. The Andantino is cooler still, and David Fanning’s booklet note informs us that the additional phrase for that marking molto rubato and all other expression marks were removed by Weinberg, so that the players could find their own way of presenting the flexibility he wanted. He could certainly trust this pair whose interpretation makes much of the movement sound questing and improvisatory.

The Allegretto cantabile finale has clear Shostakovich chamber music echoes, as Fanning mentions, specifically the klezmer elements. In fact, in his book on Weinberg, Fanning cites this work of being “one of the comparatively few…that bear out the criticism that (Weinberg) occasionally sought shelter in the shadow of Shostakovich” and mentions “near-literal borrowings”. Nonetheless most of it is still quite individual, not least the slow violin cadenza that closes the work, in which Yuri Kalnits is very commanding.

The other violin and piano sonata here, Weinberg’s sixth and last, was discovered only in 2007, twenty years after the composer’s death, and given the opus number 136bis. Its fifteen-minute single movement, on the template Moderato - Allegro – Moderato – Allegro, opens with a long violin solo. David Fanning notes its similarity to the bell theme in the finale of Rachmaninov’s First Suite for Two Pianos, and although bells often resound in Russian music from Boris Godunov to Stravinsky’s late Requiem Canticles, not many are found in a violin solo! The piano does not enter until two minutes in, and then has its own long solo at the end of this opening Moderato. This is almost texture as three-part form – solo violin, piano and violin duo, then solo piano. Whether playing together or alone, Kalnits and Csanyi-Wills hold the attention throughout this spare and haunting piece.

Arguably the most important work on the disc is the one-movement Sonata No. 3 for Solo Violin from 1979, dedicated to Weinberg’s father. Its nearly twenty-four minute continuous span make for a demanding listen, but Kalnits’s excellent performance makes a persuasive case.

-- MusicWeb International

Weinberg: Complete Music For Solo Cello Vol 2 / Josef Feigelson

Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s solo cello sonatas are considerably more interesting than his preludes for the same instrument, which I reviewed here a few months ago. They aren’t a direct response to Bach, but very much Weinberg himself, a voice not far removed from Shostakovich’s, but with occasional added flavors of Jewish melody and jazz.

These sonatas are all very much of their composer: recognizably Soviet, emotionally quite austere, harmonically bittersweet. But they are written fluently and there are terrific moments: the transition from slow movement to impassioned finale in Sonata No 2, the uncommonly charming allegretto in No 3, the ethereal muted presto of the same sonata, and the otherworldly original andante to No 4, in which cellist Josef Feigelson (who also wrote the excellent notes) points out traces of Hindemith.

On the other hand, this music won’t have mass appeal. The occasional grayness of the writing — we don’t quite have Shostakovich’s emotional range here — and the fact that Weinberg’s style appears not to have changed very much between 1964 and 1986 means that this is the kind of disc you only put on the stereo when you’re in a very specific mood, or if you’re a very specific listener. That isn’t true of Weinberg’s stunning cello concerto, a rich, generous masterwork which works through a series of lush tunes in one broad emotional circle, and I think that my slight bitterness here may be due to the fact that I was expecting something along those lines and didn’t get it. The cello concerto is currently only available on Brilliant, in its live Rostropovich box, though Chandos has recorded a similarly good cello fantasy so there may be hope.

Josef Feigelson recorded this disc, and its companion, as a compendium of Weinberg’s complete cello music in the 1990s, very shortly after the composer’s death - learning the sonatas from the original manuscripts. Certainly his playing here is not to be faulted, and, as was true of the first volume, a more impassioned advocate of the music is hard to imagine. The sound is not too close, the cello tone full and darkly rich. Weinberg’s masterwork for the instrument remains the astonishing Cello Concerto, but these sonatas are very good in their way too. If you’ve been waiting for moody Soviet solo cello work, your ship has come in.

-- Brian Reinhart, MusicWeb International

Weinberg: Cello Sonatas / Yablonsky, Liu

Russian Piano Music Series Vol 10 - Weinberg / Murray Mclachlan

"Murray McLachlan is ideal in this repertoire, playing with both sensitivity and bravura. These former Olympia recordings are excellent, with excellent piano tone and there are first rate notes by the late Per Skans. Th[is] beautifully produced discs [is] thoroughly recommended."

-- The Classical Reviewer

Weinberg: Complete Violin Sonatas, Vol. 1

WEINBERG Solo Violin Sonata No. 1. Violin Sonatas: No. 1; No. 4. Sonatina • Yuri Kalnits (vn); Michael Csányi-Wills (pn) • TOCCATA 0007 (78:08)

Violinist Yuri Kalnits and Michael Csányi-Wills recorded their program of violin music by the Russian composer Mieczys?aw Weinberg in two sessions: August 26–30, 2008, at Champs Hill, Coldwaltham (Sonata No. 1, Sonata No. 4, and the Sonatina), and July 13–18, 2009, at Moviefonics Studio in West London (the solo sonata). This constitutes the first volume in what will apparently be a complete set of the composer’s violin sonatas. Toccata bills the recordings of the First Sonata and the solo sonata as recording premieres.

The program opens with the three-movement First Sonata, which, according to David Fanning’s notes, Weinberg composed in 1943 after settling in Moscow. The sonata’s opening passages combine firmly tonal lyricism with sardonic punctuation, and although the harmonies eventually cloud over and grow less securely centered, they remain within a tonal orbit; and although its lyricism gives way to both slashing and motoric passages, in the manner of Dmitri Shostakovich, who inspired Weinberg, its melodic patterns hardly seem to cultivate unbroken ground. Kalnits sounds ardent—almost romantic—in his tone production (though he strops a keen edge on the angular passages), not only in the opening Allegro but especially at the outset of the Adagietto second movement. The engineers have captured his tonal glow, especially in the lower registers (they seem to have placed Csányi-Wills’s piano a slight distance behind Kalnits’s violin). The duo move alertly back and forth between the finale’s alternate cheerfulness and vigor and bring the sonata to an imposing conclusion.

The five-movement Solo Violin Sonata, 24-odd minutes in duration (in this performance), from 1964, inhabits an entirely different universe, less centered tonally, more dissonant, and less flowing both rhythmically and melodically. Thrusting in its first movement in a manner similar to that of Béla Bartók’s Solo Violin Sonata, it takes no prisoners—and neither does Kalnits, who enters into its more dour spirit, cavorting among its thorns. In the second movement, which begins after what sounds like an inconclusive final passage in the first, he shrieks his way through the predominantly double-stopped textures and effectively contrasts the aggressive pizzicatos with the more playful and lyrical sections to which they give way. Kalnits forcefully hammers the dissonant double-stops and chords of the ensuing Lento until quieter passages bring the movement to a close. The Presto, which begins almost immediately, recalls the finale of Bartók’s Solo Violin Sonata thematically, but without its ethnic outbursts. In fact, the entire sonata sounds like an internationalized version of Bartók’s, carrying its harmonic implications even further and stretching the violinist’s technique even less mercifully. Kalnits possesses ample resources to follow wherever Weinberg leads.

The Fourth Violin Sonata, from 1947, returns listeners to fringes of the First Sonata’s tonal world, although this sonata sounds much darker in the duo’s searing reading of its first movement. They dispel this atmosphere in an irresistible burst of energy in the second movement’s first section, and follow its biting premise through the cadenza that leads to the solemn conclusion. The duo’s expressive intensity makes this sonata a spellbinding emotional journey of discovery for listeners, as it must have been for the performers. Violinist Stefan Kirpal and pianist Andreas Kirpal also took this journey, on cpo 777 456 (David Fanning wrote the booklet notes for both releases), exploring the first movement’s more reflective side—as, for example, in the dark, complex opening contrapuntal piano solo—but no more ardent in the eloquent violin solo, and just about as incisive and visceral in the Allegro sections of the second movement. The Kirpal duo takes 19:58 for the journey, while Kalnits and Csányi-Wills completes it in 13:44. But how much of the atmosphere Andreas Kirpal creates in the opening piano solo would you trade for any added excitement in what follows?

The Sonatina, which Fanning assigns to 1949 and describes as an attempt to respond to the Soviet criticism that engulfed Soviet composers at the time, sounds more straightforward in its first movement, in which Kalnits alternately soars and engages in muted, plaintive conversation with Csányi-Wills, especially at the end. Violinist and pianist continue to explore this haunted ambiance through the second movement’s opening section, while he and Csányi-Wills wax extroverted in the middle section, which begins almost with the abrupt discontinuity of a separate movement. In their reading of the finale they mix ferocity with vigorous burlesque.

The release should provide a most auspicious introduction to Weinberg’s violin music, offering a chameleon-like variety that extends from the feral onslaught of the Solo Sonata to the profundities of the Fourth Sonata and to the outright melodiousness of the First. Strongly recommended for repertoire, performances, and recorded sound.

FANFARE: Robert Maxham

Mieczyslaw Weinberg - Complete Songs, Vol. 1 / Kalugina, Nikolayeva, Korostelyov

WEINBERG Children’s Songs. Beyond the Border of Past Days. Rocking the Child • Olga Kalugina (sop); Svetlana Nikolayeve (mez); Dmitri Korostelyov (pn) • TOCCATA 0078 (60:12 Text and Translation)

Mieczyslaw Weinberg (to use what has become the preferred spelling of a composer whose music is hard to find because of the various ways he is listed—Vainberg, Vaynberg, Weinberg) was born in Poland in 1919. He spent most of his life in the Soviet Union, and was a close friend and colleague of Shostakovich, whose influence on Weinberg was very strong.Weinberg had fled the Nazis in 1939, escaping from a horror that saw his parents and sister murdered, settling first in Minsk then hiding again from Nazis in Uzbekistan. In 1943, Shostakovich invited him to move to Moscow, where he lived until his death in 1996. Weinberg wrote 26 symphonies (one fewer than Miaskovsky!), 17 string quartets, other chamber works, a few hundred songs, sonatas and concertos for various instruments, seven operas, much incidental music for film and the theater, and much else. His music is finally being discovered by an enterprising record industry that has run out of room for more Beethoven or Mahler! If it is unlikely that Weinberg will enter the central canon in a way that Shostakovich has, it does seem as if he might occupy an important place on the periphery, perhaps similar to that now occupied by Nielsen.

It is easy to point to the Shostakovich influences on his music; one hears it in many of the songs that make up these three cycles (particularly Rocking the Child ). But he is not a carbon copy of Shostakovich, and certainly not a “poor man’s Shostakovich.” Weinberg has his own musical face, and the more of his music one hears, the more familiar it becomes. The Shostakovich relationship is handy as a tool for placing Weinberg, stylistically, to someone unfamiliar with his music. If you respond to the music of Shostakovich, you are very likely to find Weinberg attractive.

But there is a touch more restraint and straight-forward lyricism in Weinberg; he doesn’t always show the anguish, the pain that one hears in Shostakovich’s scores, nor does he demonstrate quite the same degree of sarcastic wit. Not that those qualities are not there (and there are some works, such as the Requiem, that sear with their pain), but they are perhaps just a bit less extreme in Weinberg. The Jewish influence on Weinberg’s music is strong—and although Shostakovich was influenced by klezmer and other Jewish musical traditions (just listen to the Piano Trio), it is a more integral and consistent part of Weinberg’s art, perhaps stemming in part from his roots as a pianist and conductor at a Warsaw Jewish theater. It is particularly present in the Children’s Songs and Rocking the Child , more subtle in Beyond the Border of Past Days.

The Children’s Songs, op. 13, are set to poems by Itzhol Lejb Perez; Beyond the Border of Past Days sets poems by Alexander Blok (Shostakovich’s Blok songs are among his finest); and Rocking the Child to poems of Gabriela Mistral. The Perez and Mistral poems are translated into Russian and set in that language. Thanks to Toccata Classics for providing Cyrillic and English texts (no transliteration, but that seems only a minor problem). Excellent notes by David Fanning round out the high production values.

The two singers are satisfying. Children’s Songs and Rocking the Child are for soprano, Beyond the Border of Past Days for mezzo. Both singers have a bit of what we like to call that Slavic edge, but it is not too severe. Both are masterful at shaping the music, and they and pianist Dmitri Korostelyov do not seem to be sight-reading the material at all. One feels that they are deeply into the music. Natural and well-balanced sound completes the picture. This disc is a major addition to the catalogue, introducing us to some deeply moving music.

FANFARE: Henry Fogel

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Complete Music For Solo Cello, Vol. 1

The importance of Mieczysław Weinberg’s 24 Preludes for solo cello, written for Rostropovich, lies beyond their superficial resemblance to Bach’s Well-tempered Clavier or the piano preludes of Chopin or Weinberg’s colleague Shostakovich. Instead, it resides in Weinberg’s remarkable ability to write for solo cello with almost limitless imagination, using myriad musical styles and varied techniques. These fascinating qualities are also to be found in his more expansively lyrical Sonata, a masterfully written outpouring of deep emotions. Latvian-born cellist Josef Feigelson has enjoyed a solo career spanning over three decades and champions neglected cello repertoire.

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}