CPO

Founded in 1986, Classic Produktion Osnabrück, or CPO, aims to fill niches in the recorded classical repertory, with an emphasis on romantic, late romantic, and 20th-century music.

Discover over 1,000 titles from CPO — on sale now!

Sale ends at 9:00am ET, Tuesday, May 27, 2025.

1385 products

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOPaul Graener: Orchestral Works, Vol. 2

The Symphony in D minor, subtitled “Schmiedt Schmerz” (or, “Sorrow the Blacksmith”) is a very typical, and very good example of traditional...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOFriedrich Gernsheim: Symphonies 1 & 3

GERNSHEIM Symphonies: No. 1 in g, op. 32; No. 3 in c, op. 54, “Miriam” • Hermann Bäumer, cond; Mainz PSO •...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOWeber: Complete Overtures / Griffiths, WDR Sinfonieorchester

It might be easy to overlook this new CPO disc of all Weber’s overtures. But it would be a mistake to do...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOTelemann: Complete Violin Concertos, Vol. 4

TELEMANN Overture Concertos: in G, TWV 55:G6; in E, TWV 55:E3; in g, TWV 55:g7 • Elizabeth Wallfisch (vn); dir; L’Orfeo Bar...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOPraetorius: Lutheran Choral Concerts / Cordes, Weser-Renaissance Bremen

In the new series from CPO, “Music from Wolfenbüttel Castle” we are now presenting chorales by Martin Luther in settings by Michael...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPORontgen: Violin Concertos / Ferschtman, Porcelijn, Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz

Liza Ferschtman plays these two concertos (and the Ballad) very beautifully, and they are truly lovely works. The Concerto in A minor...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOTelemann: Quatuors Parisiens Vol 1 / Holloway, Brunmayr, Duftschmid, Becker, Mortensen

TELEMANN Concerto in D, TWV 43:D1. Quartets: in a, TWV 43:a2; in e, TWV 43:e2. Sonata in A, TWV 43:A1 • John...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOChaplin: Modern Times / Brock, NDR Radio Philharmonic

Charlie Chaplin wrote most of own film scores. Although he couldn’t notate the music he did play piano and violin, and was...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

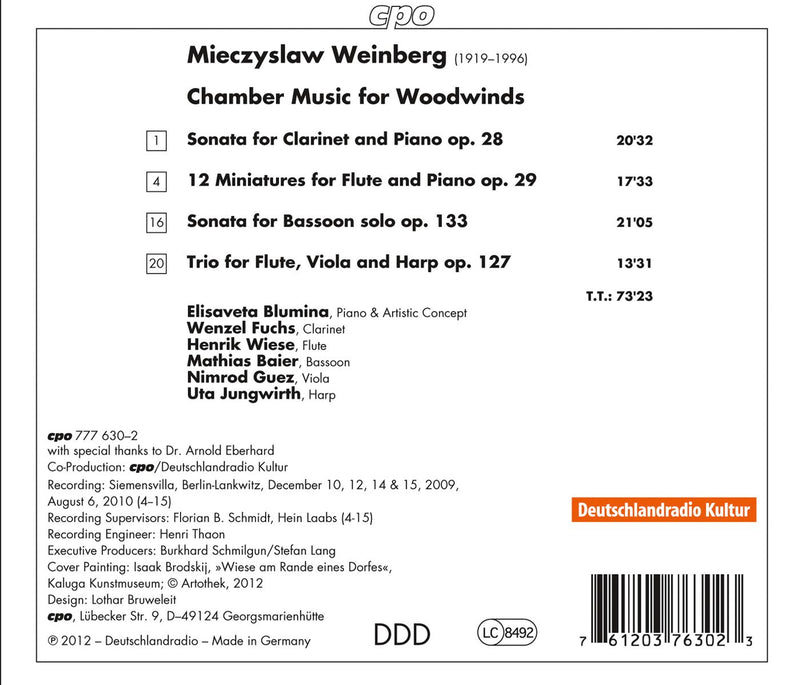

CPOMieczyslaw Weinberg: Chamber Music For Woodwinds

Performances of beauty and great skill - more please! The wait for the music of a particular composer to be recorded when...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOKalliwoda: Symphonies No 5 & 7 / Spering, Neue Orchester

These stunning performances, magnificently recorded, belong in every serious collection. This disc is as outstanding musically as it is historically important. Johann...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOvoces quietis

The male quartet, schnittpunktvokal,is formed of three brothers and one bass singer. This recording features moving sacred songs. Critics rave about the...

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPO

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

CPOKabalevsky: Cello Concertos 1 & 2; Colas Breugnon Suite / Oue, Thedeen, NDR Philharmonic

Kabalevsky's natural talent was for catchy tunes, clear structures and audience-pleasing rhythms; beautifully crafted, eminently accessible, full of wit and charm. �...

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}