Foghorn Classics

25 products

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

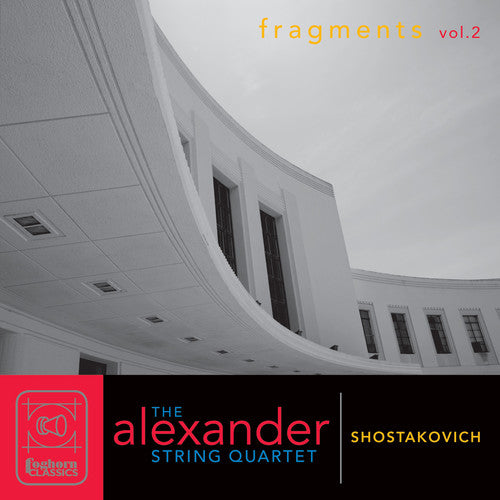

Foghorn ClassicsFragments Vol 2 - Shostakovich / Alexander String Quartet

These fabled works dating from 1960–1975 represent some of Shostakovich’s most bitterly frank, occasionally transcendental essays for the string quartet. At times...

$37.99January 01, 2007 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsFragments Vol 1 - Shostakovich / Alexander String Quartet

Captured here, on three discs, is the first half of the Alexander String Quartet’s complete Shostakovich cycle. Superbly recorded at the American...

$37.99January 01, 2006 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

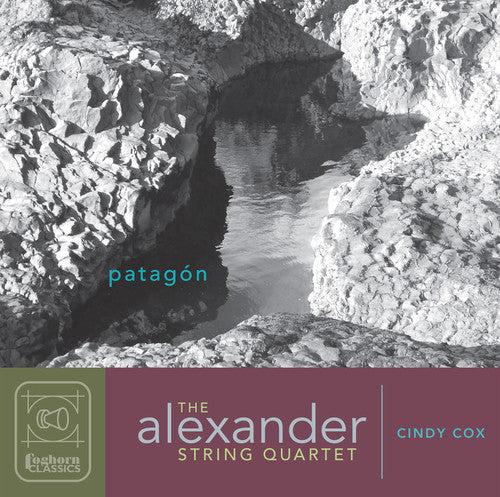

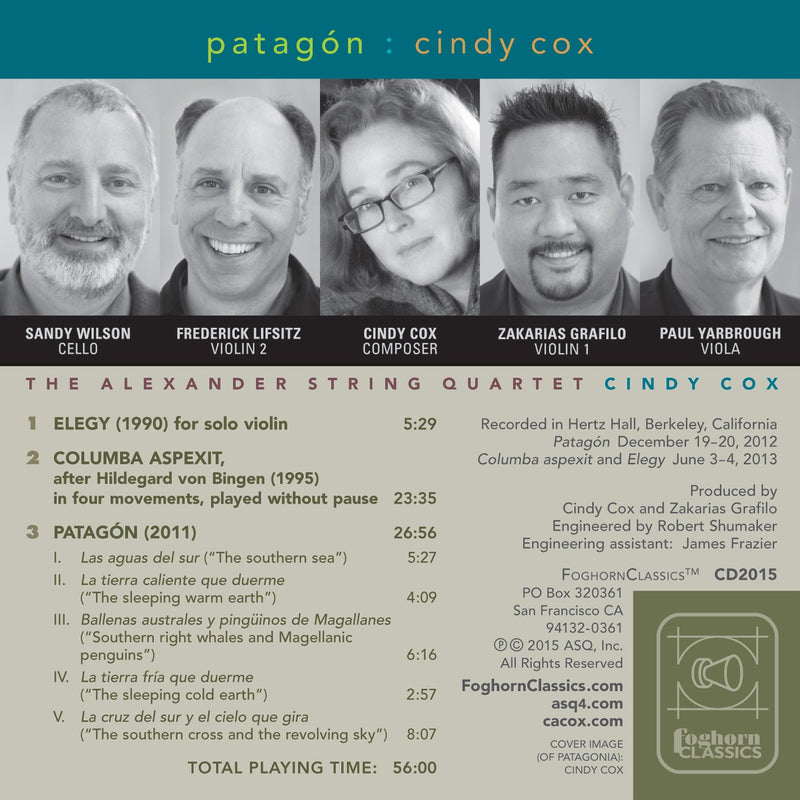

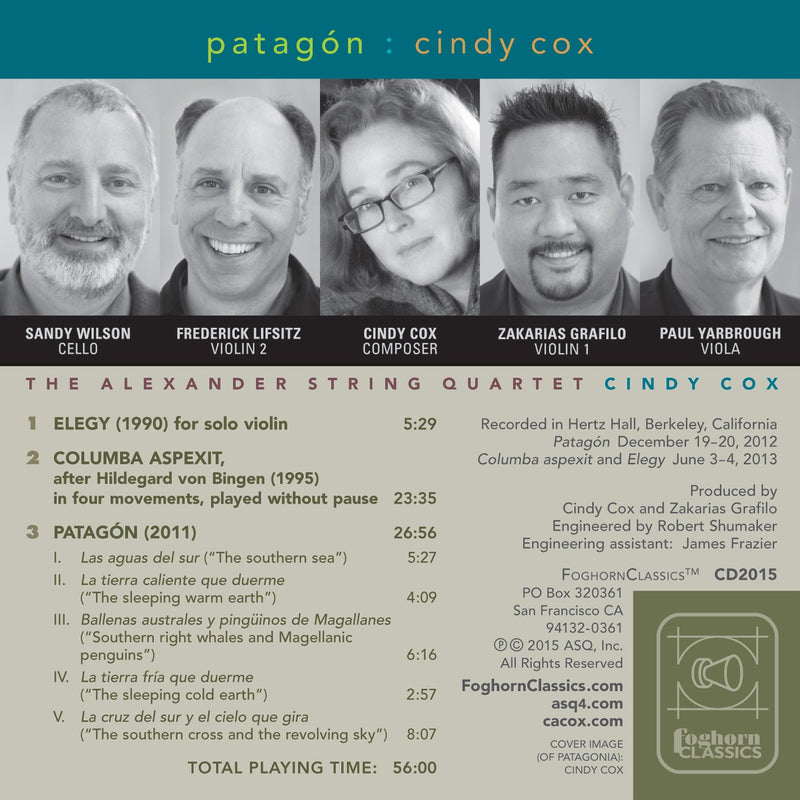

Foghorn ClassicsCindy Cox: Patagon

Cindy Cox's new string quartet, Patagón, which takes its title from an ancient name for the region of Patagonia, was inspired by...

$18.99October 30, 2015 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsApotheosis, Vol. 1: The Final Quartets of Mozart / Alexander Quartet

The Alexander String Quartet turns its attention to Mozart’s last years, beginning with this recording of the final four quartets (the first...

$29.99March 08, 2019 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsBrahms, Schumann: Piano Quintets / Joyce, Alexander String Quartet

SCHUMANN Piano Quintet. BRAHMS Piano Quintet • Alexander Str Qrt; Joyce Yang (pn) • FOGHORN 2014 (70:24) One would think that the...

$16.99January 01, 2014 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsBeethoven: The Complete String Quartets / Alexander String Quartet

One of the very finest sets available. “ A majority of musicians would probably agree in regarding Beethoven’s string quartets as the...

$85.99January 01, 2009 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsBrahms: The String Quintets & Sextets / Alexander String Quartet

BRAHMS String Sextets Nos. 1 1 and 2 1. String Quintets Nos. 1 2 and 2 2 • Alexander Str Qrt; 1,2...

$29.99January 01, 2014 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

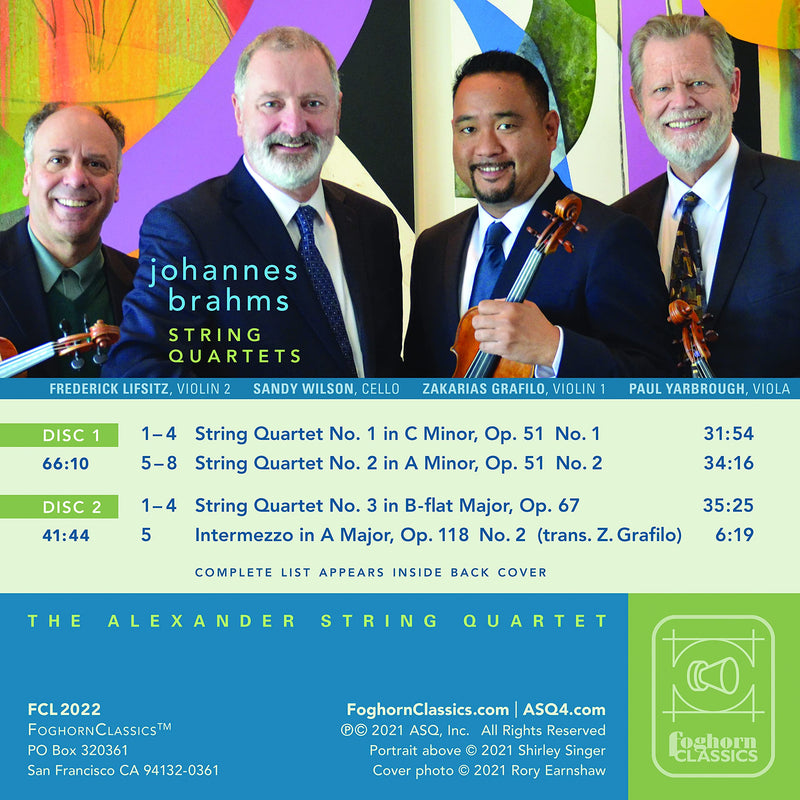

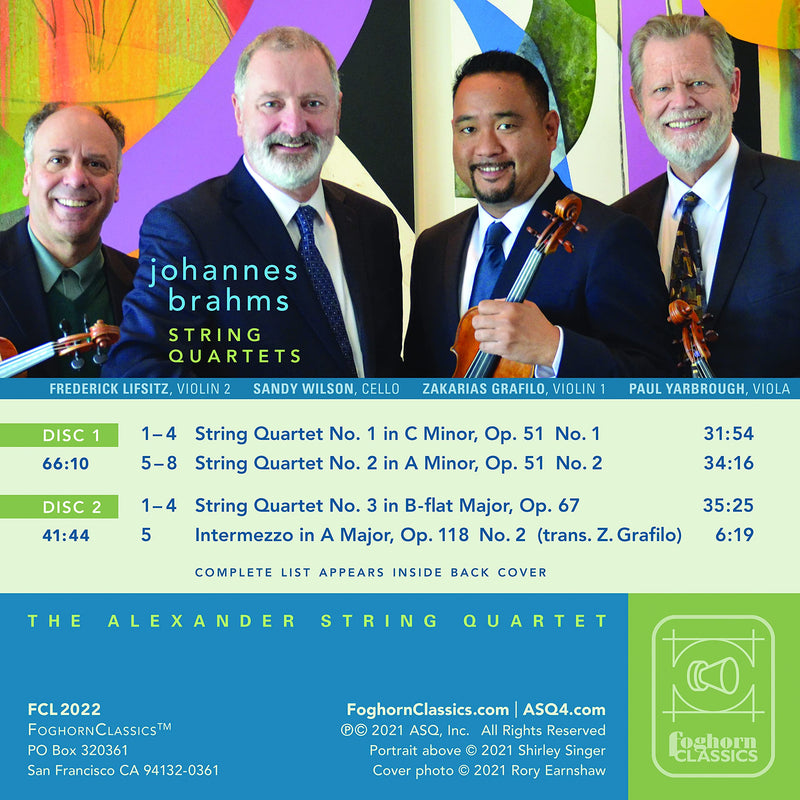

Foghorn ClassicsBrahms: Complete Quartets for Strings / Alexander String Quartet

The Alexander String Quartet launches its 40th season with this recording of Brahms String Quartets — plus Brahms’ Intermezzo (transcribed for string...

$29.99November 05, 2021 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn ClassicsBartok & Kodaly: The Complete String Quartets

BARTÓK String Quartets No. 1–6. KODÁLY String Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 • Alexander Str Qrt • FOGHORN 2009 (3 CDs: 205:55)...

$37.99January 01, 2013 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Foghorn Classics

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

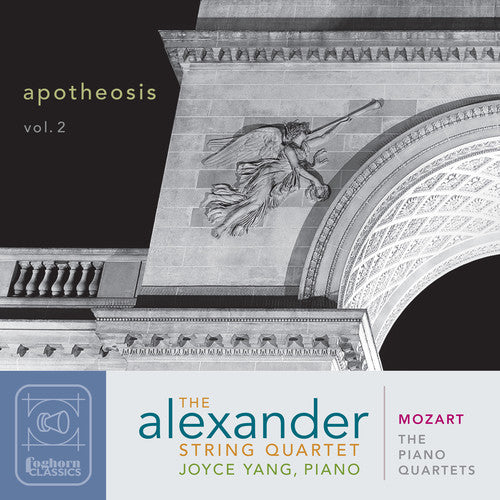

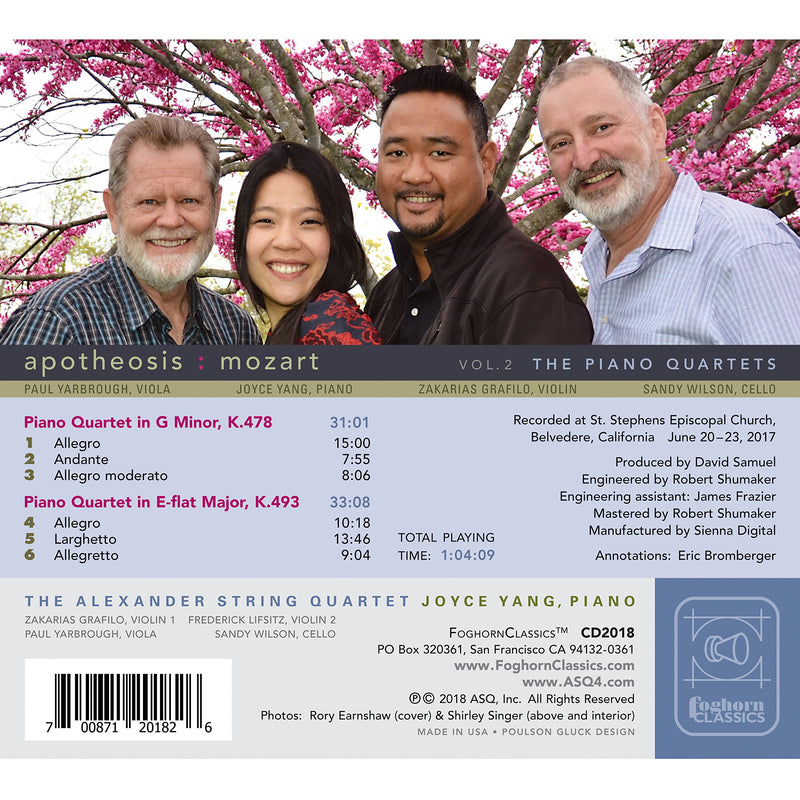

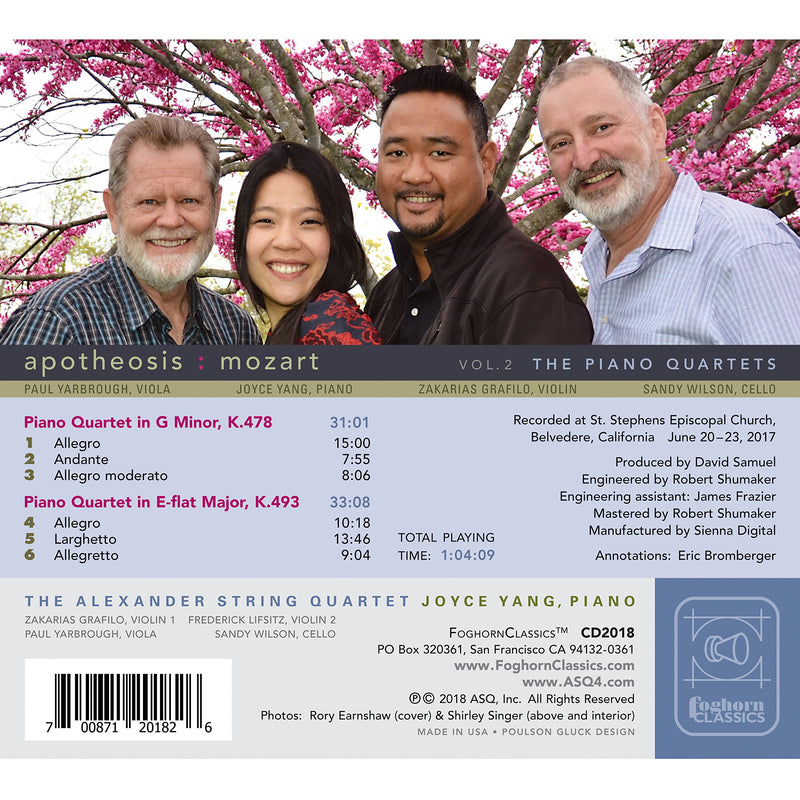

Foghorn ClassicsApotheosis, Vol. 2: Mozart Piano Quartets / Yang, Alexander String Quartet

Maintaining focus on Mozart’s last years, members of the Alexander String Quartet join with electrifying and much-lauded pianist Joyce Yang on this...

$18.99July 27, 2018

Fragments Vol 2 - Shostakovich / Alexander String Quartet

Alexander String Quartet:

Zakarias Grafilo, Frederick Lifsitz: violins

Paul Yarbrough: viola

Sandy Wilson: cello

Fragments Vol 1 - Shostakovich / Alexander String Quartet

Alexander String Quartet:

Zakarias Grafilo, Frederick Lifsitz: violins

Paul Yarbrough: viola

Sandy Wilson: cello

Roger Woodward: piano

R E V I E W:

"There’s an irony about writing reviews, and I am sure there are colleagues who would agree, that it is relatively easy to write a critical commentary of a performance or recording which has plenty of faults, or which is just plain beige. One can get down to work, pointing out weaknesses while balancing these against the positive aspects of a production and that of the competition, and before you know it the job is complete. Listening to these new Shostakovich recordings from the start, my immediate impression was that the playing lacked some of that intense grittiness I’m more used to hearing from my principal reference, that of the Fitzwilliam Quartet on Decca. I have spent a lot of time with the Alexander Quartet recordings however, partially thanks to a botched hernia operation which kept me off work for longer than necessary. As a result of this extra listening, I’ve come to appreciate how, as with their survey of the Beethoven Quartets, this ensemble clearly approaches the music with a view to its place in the composer’s timeline as well as purely on musical/aesthetic grounds. Both they and the Fitzwilliam Quartet allow the sunnier aspects of the music to sing through in the Quartet No.1, with those shades of angst held well in proportion. The dramatic extremes of the Quartet No.2 are, I think, more open to wider interpretation – is it dark or light, secretive or intimate? The Fitzwilliam Quartet’s view is I feel more on the dark side, bringing out the sense of mortality that the composer’s wartime experiences introduced. The Alexander Quartet introduces some more of the dancing qualities in the opening, perhaps emphasising more of the celebrations of heroism in the air at the time. Zakarias Grafilo has been the Alexander’s 1 st violin for a while now, having replaced Ge-Fang Yang in 2000. His fine, deep tone gives the second movement’s Recitative a strong character, lightening like the opening of a stained-glass window into the faux-naive Romance which follows. Their third movement Waltz for me conjures the atmosphere of a smoky, dark wood-panelled interior, with this music coming to us on the soundtrack of a black and white film – the 78 rpm player’s horn introducing an element of sculpture into the picture. The muted strings repress the ebullience of the second section, maintaining that hazy image and introducing Shostakovich’s signature neurotic turbulence of conflict and struggle. The final Adagio Theme with Variations begins with less of a symphonic scale than with the Fitzwilliam, but this more gentle opening allows the music to develop and grow, the full impact of the final bars providing a true climax.

For the Quartet No.3 I can offer a comparison with that lovely DG recording with the Hagen Quartett. The greater transparency this 2006 recording offers over the Fitzwilliam’s is punctuated with needle-sharp articulation and wide contrasts of tone and character. With equal technical panache and some subtle twists the Alexander Quartet create their own view on this seminal work. The opening is a little less jaunty than with the Hagens, more of a swaggering walk than a quasi-jolly dance. As a result, their sound in the following counterpoint is less urgent but no less characterful – it certainly avoids becoming laboured and static. Rather than go all-out with the pesante viola triad in the opening of the second movement, this becomes more of an accompaniment, allowing the flow of the upper instruments their full expression. On balance, the Alexanders for some reason sound slower almost through the entirety of this quartet, though the timings don’t always bear this out. They somehow convey the feeling of creating space around the notes even where the textures in the music would seem to make this as good as impossible. There is certainly no lack of urgency in the Allegro non troppo, and the subsequent Adagio refuses to ramble and lose shape, in this case shaving almost half a minute off the Hagen’s timing. I’m torn between these two recordings of this quartet, which has to be a good thing. I suppose a smidge more forward momentum might have given the Alexander Quartet the edge in the final Moderato, and a tad greater sense of involvement in the in-between tracts of this arguably over-long movement. I do however admire their sense of apocalyptic passion where the music demands, and their elegance of tone in the relatively high-pitched tessitura in this quartet. Come back to me in a year’s time and I’ll probably still be humming and hawing. The Hagen Quartett is lively and filled with contrast, but there are one or two moments of fast gear-change where I ‘notice’ them, not really a faltering, but having a moment of marginal discomfort where the Alexanders sail on regardless.

Quartet No.4 is muted in more ways than one, with two of its movements being played with mutes, giving the instruments that hazy, secretive feeling. The rest of the piece is also very subdued in atmosphere, though the Alexander Quartet are sensitive to the changes of internal colour in each section, including the dance-like feel of the penultimate Allegretto and ultimately protesting final movement. The final blast of a foghorn is unfortunate. Once is a novelty, more than that is disrespectful to all concerned, and I’ll leave it at that. Coming back to this piece from the Fitzwilliam Quartet, and I find their silvery tone has a more chilling effect – less warmly intimate and more intense. It’s not that the Alexanders are cosily fireside cheerful, but by degrees one does sense something more of a connection with the Russian character from the Fitzwilliam Quartet. It’s as if the Alexander players take the work as the private statement it became, hidden from the public until the death of Stalin in 1953. From the Fitzwilliam Quartet it’s Shostakovich’s view on the Russian people through the wrong end of a telescope, dancing like puppets, or, awaiting the thaw; suppressed celebrations going on merely in their minds. These are two views with equal validity – and at least the Alexander Quartet is a clear winner in terms of intonation.

Like its predecessor, the Quartet No.5 was held back from public performance until 1953, and with its dissonant complexities it’s not really hard to hear why this was the case. Eric Bromberger in his excellent booklet notes points out that this is one of the darkest in the entire cycle, and at over 30 minutes is a serious proposition for both players and audience. I won’t say the Alexander Quartet make it sound easy, but neither do they seem fazed by the extremes in the first movements. It is in this magisterial mastery of such technical obstacles that they win out over many other recordings, the tonalities remaining clear even when everyone seems to be trying to play as high as possible all at once. The jaunty character of the Quartet No.6 always comes as something of a surprise after all that almost silent intensity at the end of the fifth. Shostakovich had re-married, somewhat impulsively it has to be said, but the sunny nature of the music reflects some of the optimism he must have felt at the time. The Alexander players stroke the softer phrases with appropriate affection, but don’t hold back on some of the passages of conflict and strange passion in the opening Allegretto. The contrasting lyrical and rhythmic characters in the second movement are highly attractive, just the right amount of symbolism – if that’s what you are looking for: like two opposites which somehow attract and harmonise.

Taking a break from the quartets, and I was delighted to see some of the Op.87 Preludes and Fugues, originally for piano, and arranged here for string quartet by Zakarias Grafilo. The effect with these arrangements is quite different to that of the same music on piano, but Shostakovich’s idiom in these pieces works extremely well for strings. The Alexander Quartet balance the voicing with easy expertise, which is essential for any kind of comprehension in this kind of contrapuntal music, but I was surprised to hear a moment or two of dodgy intonation in the Prelude & Fugue in C minor. The famous Prelude & Fugue in D-flat major opens almost inevitably rather heavier with strings, but the ear soon accepts the music on its own terms, and the textures are relieved by some gorgeously witty and well-executed pizzicati. The fugue itself becomes a new Shostakovich animal in its own right, with even more of the neuroses than you have with the piano version. The darkness of the Quartet No.13 is lightened in the final disc of this set, as it concludes with the sprightly Op.87 No.17. The parallel movements in the prelude create some interesting sonorities, and the fugue comes across with an almost naive sense of simplicity. Op.87 No.1 could possibly have used a little more space in the famous opening C major prelude – the strings could have sustained those chords so nicely, but at least they prevent the music turning into a church chorale. The fugue is one of Shostakovich’s most noble statements, and works well with strings. As ever with such transparent music, it is the intonation which proves more problematic than one might expect, and this fugue is full of niggly augmented and diminished intervals which do create some minor problems. My hat goes off to Zakarias Grafilo for his excellent arrangements however, and these pieces certainly make for equally, if no more effective string quartet music than some of those Bach Fugues.

Another substantial extra is the Piano Quintet in G minor Op.57. Joined by the powerful piano playing of Roger Woodward, the quartet seems to shrink in size a little, and I would personally have had a little less presence in the piano sound. It’s partly sheer balance, but also that the piano is a fraction too far forward, which meant I felt a bit bludgeoned when those repeated high notes come in. The performance is very good however. I compared it with one of my favourites, that with the Nash Ensemble on Virgin Classics, and in terms of tempi and timings there is little to choose. Ian Brown’s piano is equally powerful here, but as a listener one feels at a marginally more respectful and realistic distance. The Nash Ensemble strings are a little more nasal, the Alexander ‘sound’ richer and warmer in general. As with the differences in character with the Fitzwilliam Quartet, this gives the Nash Ensemble an impression of greater intensity. Taken in isolation the Alexander performance is fine, with its own forceful sense of communication. It doesn’t however quite take your soul to the same pain barrier as some performances. I was interested to see that the 1950 recording made by Shostakovich himself with the Borodin Quartet differs from these interpretations, with significantly longer Fugue and Intermezzo movements, adding around two minutes to each. The sustained emotion created in these movements does take you to different worlds, especially in the Fugue. It is intriguing to make such comparisons and as a historical document this recording is priceless, but I have to admit the transfer on my 1991 Vogue CD is pretty atrocious in parts.

Returning to the quartets, and we’re up to No.7. Remarkably compact at around 13 minutes, the striking pizzicato feature in the first movement is taken toothsomely by the Alexander players, with plenty of resonance and a fearless attack. Absolute rhythmic security is also an essential aspect of this piece, not only in the fast ostinati of the opening and final movements, but also in the wandering legato lines of the second. The Hagen Quartett undercut the Alexander by over a minute in this piece, a result of a brisker Lento and wilder finale. The Hagens have a lighter, more skittish view of the complex final movement, and it’s a question of whether you prefer this over the Alexander’s greater heft. There’s no doubt that the Hagen Quartett is extremely exciting, but you almost feel you have to look the other way in the presence of such almost indecently showy virtuosity. I do appreciate Paul Yarbrough’s rough viola entries in this movement, and find the overall impression to have more than enough grit and spirit. The final pages are indeed ‘haunting and moving’."

-- Dominy Clements, MusicWeb International

Cindy Cox: Patagon

Apotheosis, Vol. 1: The Final Quartets of Mozart / Alexander Quartet

The Alexander String Quartet turns its attention to Mozart’s last years, beginning with this recording of the final four quartets (the first of a three-volume set which will add his other great chamber works from that period). Eric Bromberger’s liner notes are prefaced by comments from ASQ violist Paul Yarbrough, excerpted here: “Taken as a whole, Mozart’s works for string quartet, piano quartet, viola quintet, and clarinet quintet are a monumental accomplishment, as they codified the evolution of classical chamber music. He had taken Haydn’s brilliant efforts with the string quartet and elevated and broadened the genre, while adhering to Haydn’s formal and conversational precedent. But however much Mozart’s late chamber works conform, they are never “conformist.” They still have the capacity to be stunningly original, and even, especially for the listeners of the time, shocking.” Now in its 35th season, the Alexander String Quartet’s discography includes major cycles by Bartok, Kodaly, Mozart, Shostakovich, and Beethoven. ASQ is also an important advocate of new music, with over 35 commissions and premieres.

Brahms, Schumann: Piano Quintets / Joyce, Alexander String Quartet

One would think that the Schumann and Brahms piano quintets would make natural partners on disc; yet, they’ve been paired together fewer times than I’d have thought. I found no more than half a dozen such couplings, and interestingly, of those, only one (not counting the present Alexander Quartet’s version) is anywhere near recent, and that is a 2007 recording with the Artemis Quartet and Leif Ove Andsnes on Virgin, which received a less than favorable review from me in 31:4. Three others fall into the historical category: a recording issued by Pearl with the Busch Quartet and Rudolf Serkin (Brahms, 1938; Schumann, 1942); a recording issued in a three-disc set by Testament with the Hollywood Quartet and Victor Aller (Brahms, 1954; Schumann, 1955); and a recording by Doremi with the Tel Aviv Quartet and Pnina Salzman (Brahms, 1974; Schumann, 1983). There’s also a pairing of the two works on a 2000 Globe CD, featuring the Rubio Quartet and Paul Komen.

This led me to wonder why these two piano quintets by two men who held each other in high esteem, and whose lives intersected in very personal ways, would not be joined together on disc more often. Then, listening to them, one after the other, as they’re programmed on the Alexander’s CD—the Schumann first, the Brahms second—some possible reasons presented themselves.

To begin with, the Brahms Piano Quintet dwarfs the Schumann, and not just in its duration, which is some 12 minutes longer, but in the thickness of its textures, the weightiness of its material, and especially the ponderousness of its piano part. Schumann, the keyboard virtuoso who wrote such magnificent music for his own instrument, also seemed to understand intuitively how to combine piano and strings in a way that was balanced and transparent and that allowed for the strings to be heard on an equal footing. He leveled the playing field. Steven Ritter, in a 34:1 review of the Quintet performed by the Leipzig Quartet and Christian Zacharias on MDG, wrote, “Schumann in this piece knew what he was writing for, and the balance among the strings with the piano is well-nigh perfect.” Exactly right.

Brahms, too, was reputedly a formidable pianist, but his writing for the instrument, at least in his earlier works, was of a different nature. It was muscular, bulky, and dense. For the string players in his Quintet, it’s a constant struggle to be heard.

Then there’s the music itself. Much of Schumann’s Quintet gives off a feeling of spontaneous inspiration. For the most part, it’s a buoyant, ebullient work. Brahms’s Quintet is not spontaneous sounding at all. Much of it, with its convoluted rhythmic contortions, sounds laboriously worked out. Add to that a score containing some of Brahms’s most violent music, and in the very dark key of F Minor—which, according to Christian Schubart’s Ideen zu einer Aesthetik der Tonkunst (Ideas for an Aesthetic of Sound Art) (1806), expresses “deep depression, funereal lament, groans of misery, and longing for the grave”—and you have a work that’s grim, desperate, and brutal in three of its four movements. Can there be any more sudden or crueler ending to a piece than the fateful three-note thud that decapitates the Finale dead in its tracks?

The piano quintets by Schumann and Brahms are indeed very different works, which, on emotional and psychological levels, probably wouldn’t make compatible marriage partners.

There’s also the age difference to take into account. Schumann composed his Quintet in 1842, more than 10 years before he and Clara met Brahms for the first time in Düsseldorf in 1853. By the time Brahms completed his Piano Quintet in 1864, Schumann had been dead for eight years.

But Brahms’s Quintet was one of those works that had a lengthy gestation and a difficult birth, struggling to find its final form. Originally, it took shape as a two-cello String Quintet. Had Brahms not destroyed that first version, it would have been his only string quintet scored for two cellos, following the example of Schubert’s great C-Major Quintet. As it turned out, Brahms’s only two extant string quintets, opp. 88 and 111, are scored for two violas, following the examples of Mozart.

Unhappy with the piece as a String Quintet, Brahms next revised it as a Sonata for Two Pianos. He was well enough satisfied with that version not to have destroyed it, but Clara Schumann and Hermann Levi, who performed the two-piano version together in concert, both felt that the piece needed a bigger, perhaps orchestral, treatment. Brahms wasn’t ready yet to write a symphony, but he took his friends’ advice to heart, and rearranged the score one last time as the Piano Quintet we know today. The two-piano version, however, was preserved and published as op. 34b. But filed under the category of “can’t leave well-enough alone,” the destroyed two-cello Quintet version was exhumed in a speculative reconstruction by Anssi Karttunen and recorded at least once that I know of, on a Toccata Classics CD (TOCC0066).

The Alexander’s Schumann is indeed breathtaking, as much for its sweeping lyricism and emotional responsiveness to the music’s impassioned Romantic gestures, as for its technical precision, ensemble balance, and tonal bloom. It stands head and shoulders, by far, above any of the recent recordings of the work to come my way. I already mentioned the disappointing Artemis effort; and even more recently, I found the Fine Arts Quartet’s entry with pianist Xiayin Wang on Naxos “workmanlike and professional, but not emotionally moving or inspiring.” Yet another letdown was a live recording from the Heimbach Festival with Christian Tetzlaff, Lars Vogt, and friends, a performance I found wanting for a bit more rehearsal time.

Quite honestly, until the arrival of this new version of the Schumann from the Alexander Quartet and Joyce Yang, my favorites have been a performance by the Schubert Ensemble on ASV, reviewed in 30:3, and the classic 1966 recording by the Guarneri Quartet with Arthur Rubinstein, a review of which (assuming it was reviewed) most likely predates the Fanfare Archive. The Alexander’s Schumann is simply wonderful, taking pride of place among all others with which I’m familiar.

The Brahms Quintet, too, is special. The hair-on-fire Scherzo, in particular, is a guided tour through Brahms’s rhythmic arsenal. If the players thoroughly appreciate the pulse-quickening, heart-pounding effect this movement is intended to have, and they deliver it accordingly, it should make you want to jump out of your skin. No one, of course, has literally ever done such a thing; it’s just an expression, like being beside oneself, which, according to quantum theory, at least, is a possibility. But I have to say that the Alexander’s performance is super-charged and electrifyingly exciting. Needless to say, the ensemble’s terrific reading of Brahms’s Piano Quintet is not limited to just the Scherzo. This new recording of the Schumann and Brahms piano quintets will be a serious contender for my year-end Want List.

FANFARE: Jerry Dubins

Beethoven: The Complete String Quartets / Alexander String Quartet

“ A majority of musicians would probably agree in regarding Beethoven’s string quartets as the highest peak in the whole range of chamber music.” Roger Fiske (‘ Chamber Music’, ed. Alec Robertson, Penguin Books, pub.1957)

Over the last decade or so I have had the opportunity to play and consider the merits of several sets of the complete Beethoven string quartets. In particular I recall the accounts from the Bartók Quartet/Hungaroton, Juilliard Quartet/Sony, Italian Quartet/Philips, Guarneri Quartet/BMG RCA, Alban Berg Quartet/EMI Classics, Lindsays/ASV, Medici Quartet/Nimbus, Amadeus Quartet/Deutsche Grammophon and Takács Quartet/Decca.

My benchmark of the complete quartets has been the series from the Takács on Decca. The 7 discs were recorded in 2001-04 at St. George’s Church, Bristol and released on three separate volumes: early quartets 470 848-2, middle quartets 470 847-2 and late quartets 470 849-2. With the advantage of splendid sound quality the assured Takács play with impressive momentum, vitality and intensity. Their dynamics are broad yet their liberal use of vibrato never feels excessive. Perfectly matched, these are coherent performances without any hint of ostentation.

There are three sets of the late quartets and Große Fuge that deserve attention. I have enjoyed the Emerson accounts. They demonstrate awesome energy and robust character. They were recorded at the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, NYC in 1994-95 and issued on Deutsche Grammophon 474-341-2. Also deserving of praise are the Alban Berg Quartet (ABQ) who play with great intensity and impeccable security of ensemble. The ABQ were recorded live in 1989 at the Mozartsaal Konzerthaus, Vienna (EMI Classics 4 76820 2). I also admire the superbly performed historic accounts by the Busch Quartet recorded in mono at the Abbey Road Studios, London and the Liederkranz Hall, NYC in 1932-37 (EMI Classics 5 09655 2). Although these are successfully remastered performances the Busch is not a set that I often play these days for pleasure as I find it hard to get past the seventy year old sound quality.

There are several single discs that can stand up to the very best accounts included in the late quartets or complete sets. One of the finest of these involve accounts of the Quartet in B flat major, Op. 18/6 and Quartet in E flat major, Op. 127 from the exceptional Henschel Quartet who recently celebrated their 15 year anniversary since formation. These performances, recorded in 2004 at Munich, are both sparkling and exhilarating and reveal considerable empathic insights (Arte Nova 82876 63996 2) ( see review).

For performances on period instruments one need look no further than the accounts from Quatuor Mosaïques on Naïve. Mosaïques must surely be the greatest string quartet ensemble of our time performing on authentic instruments. Recorded at the Grafenegg Schloss, Alte Reitschule in Austria there are currently three single volumes: Op.18/5 and 6 from 1994 on Naïve E 8541, Op.18/1 and 4 from 2004 on Naïve E 8899 and Op.18/2 and 3 recorded in 2005 on Naïve E 8902. These beautifully played and recorded performances inhabit a rather reserved and unidiomatic world. For those who prefer their Beethoven string quartets played less cautiously with lashings of additional spirit on instruments with modern set-ups there are better opportunities in the catalogues. Yesterday in the Times 2 newspaper I read a review of the Mosaïques playing at the Edinburgh International Festival at the Usher Hall on 24 August 2009. Their recital was interrupted on four occasions: twice for illness in the audience and twice for broken gut strings. The fragility of using authentic instruments must undoubtedly be frustrating when playing in recital but thankfully technical malfunctions do not affect the enjoyment of their recordings.

Outside the USA the Alexander String Quartet (ASQ) may be new to some. The ASQ was formed in New York City in 1981 and are now San Francisco based. In 1985 they became the first American ensemble to win the London International String Quartet Competition gaining the jury’s highest award and also the Audience Prize. It is a mark of their consistency and discipline that they celebrated their 25th Anniversary in 2006. In 1996/97 with former leader Ge-Fang Yang (their first violin from 1992-2002) the ASQ recorded their first complete Beethoven quartet cycle for BMG's Munich-based label Arte Nova. The recordings produced over a three year period at St. Stephens Church, Belvedere, Marin County in California seem to have been issued initially as nine individual discs, released as a set in 1999 on Arte Nova Classics on 74321-63637-2 and subsequently reissued and repackaged on Arte Nova ANO 636370 ( see review).

For Foghorn these new performances were recorded in 2008 in three separate sessions over 19 days. “ For their superb sound qualities” the ASQ have chosen to play the Ellen M. Egger quartet of loaned instruments constructed by the San Francisco maker Francis Kuttner about twenty years ago. Cellist Sandy Wilson tells me that the Kuttner set is, “ superb to play - wonderfully adjusted and I dare even say ‘easy’ and responsive in every way.”

To record the complete Beethoven quartets is a marvellous achievement and I can only imagine all the hard work and scrupulous preparation that the ASQ must have put in. I have enjoyed and have been consistently impressed with their excellent performances. They took this listener through the odyssey of Beethoven’s string quartets reaching deep inside the core of the music. The performances are unfailingly fresh and musically compelling. The interpretations are crisp and polished, full of perceptively observed detail; alert to the smallest change of accent and nuance. Tempos are never over-forced and neither are the dynamic contrasts. At the same time they are never afraid of imparting a vigorous bite to the Scherzos. Especially impressive is their superb intonation and immaculate ensemble whilst each player remains a solidly characterised individual. First violin Zak Grafilo is smoothly expressive, responsive and flawless throughout. Today I would place Grafilo in the same elevated league as eminent quartet leaders: Christoph Henschel of the Henschel, Edward Dusinberre of the Takács, Jan Talich of the Talich, alternating leaders Eugene Drucker and Philip Setzer of the Emerson and Corina Belcea-Fisher of the Belcea.

Their use of vibrato is careful. I was interested in comparing the amount of vibrato used by some of the rival sets. Quatuor Mosaïques, as one would expect with their authentic performance practice are extremely sparing yet I was also aware of their narrow dynamic range. The Henschels on Arte Nova employ vibrato judiciously with the Takács on Decca exercising a slightly more liberal approach. The accounts that employed vibrato more substantially included the Borodins on Chandos, the Italian Quartet on Philips, the Emerson on Deutsche Grammophon, the Alban Berg on EMI, the Amadeus on Deutsche Grammophon, the Lindsays on ASV and the Busch on EMI.

I have made some observations on the accounts that I have enjoyed the most. Divided into Beethoven’s three stylist periods the Foghorn set follows a generally chronological order. The first volume comprises the op. 18 works, composed in 1798/1800 and dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz.

The Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18/1 is the finest of the op. 16 set. I loved the grand gestures from the ASQ in the Allegro con brio. In the Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato the deep concentration from the players is remarkable, bringing out the music’s tragic and intense nature said to be inspired by the tomb scene in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The glittering brilliance of the vivacious Scherzo is followed by the bubbly Allegro, Finale played with sureness and a ‘light on its feet’ quality.

The five middle quartets composed between 1805 and 1810 are on volume 2. The substantial F major Quartet No. 8, the first of the op. 59 ‘ Razumovsky’ set, is arguably the most impressive. There is a heady mixture of gritty determination and underlying tenderness in the opening Allegro. The awareness and ensemble from the ASQ is impeccable in the idyllic mood of the Scherzo. Dreamy and melancholy, nothing is exaggerated and everything is refined in the Adagio; a magnificent movement and a great achievement. Based on a Russian folk-song in the Allegro, Finale the players convey a substantial feeling of intensity, maintaining shape and momentum.

A particular favourite is the Quartet No. 10, Op. 74 known as ‘ The Harp’. The ASQ in the restless opening movement Poco Adagio: Allegro brim over with ideas, often sharp, brash and bold, sometimes mellow and submissive. I love the way the beautiful and refined song-like Adagio ma non troppo balances a sense of nostalgic longing with restraint. Hammering out its fierce rhythms the playing of the exultant Scherzo leaves one breathless. Impressive is the gear shift at 3:44 where the dynamic weight lessens markedly. Rather reserved in manner, the Finale, a graceful theme and set of variations, gives way to a short and thrilling Coda.

Evidently Beethoven himself gave the nickname ‘ Serioso’ to his Quartet No. 11, Op. 95. The terse and compact opening Allegro con brio feels hewn from stone, conveying a keen effect of forward motion. An underlying tension prevails in a Adagio ma non troppo that never allows the listener completely to relax. Boisterous by threat rather than by overt aggression the Allegro assai vivace ma serioso serves as the Scherzo. I was struck by a slow introduction of dark foreboding in the Finale that shifts swiftly to music of a joyous celebratory character. At 4:15 the boisterous Coda brings an astonishing mood-change with a headlong race to the finishing post.

Volume 3 contains the five late great string quartets and the Große Fuge - all composed in 1824-26. Widely acknowledged as remarkable music and so ahead of its time this new dimension in chamber music still remains challenging for performers and listeners alike.

In the Quartet No. 12 in E flat major, Op. 127 I was especially impressed with the immense second movement Adagio ma non troppo e molto cantabile. It is almost twice as long as the next in length. Designed as a theme and variations with Coda this is full of glorious writing often of a contemplative quality played with passionate conviction. I found the Allegro, Finale a welcoming movement of childlike innocence. Some of the rhythms have a gypsy feel providing a contrast with a certain rustic simplicity.

An enigmatic masterpiece of the genre the Quartet No. 13, Op. 130 is a long work, lasting over 42 minutes in this performance. The score embraces a breathtaking ambit of emotions from the simply playful to ecstatic outpourings of tortured angst. The Cavatina marked Adagio molto espressivo is remarkable.

The Quartet No. 14, Op. 131 is said to be Beethoven's favourite of the late quartets. It consists of seven movements designed to be played without a break. The centre-piece is the fourth movement Andante ma non troppo e molto cantabile - a set of six variations based on a simple theme. This is inspired playing here done with touching expression that yet demonstrates the ASQ’s firm grip on the music. The Finale, Allegro is performed with vigour and exuberance. The assured players provide an almost relentless forward momentum that only briefly stops for breath.

Intended as Beethoven’s original Finale to the Quartet in B flat major, Op. 130 the colossal Große Fuge in B flat major was published separately as his Op. 133. The individuality of the Große Fuge is remarkable. It comprises three fugal sections each with contrasting tempi. For many listeners it’s a tough nut to crack. The ASQ are uncompromising in their power, intensity and spiritual depth.

In A minor the Quartet No. 15, Op. 132 has a conspicuous five movement arch-structure. It’s a massive work that here takes some 45 minutes. The central movement Molto Adagio - Andante, at nearly 17 minutes, is by far the lengthiest and the keystone of the score. Written by Beethoven after a period of illness he named this movement his ‘ Holy Song of Thanksgiving by a Convalescent to the Divinity…’ This series of double variations uses a chorale melody contrasted with an energetic section. I was struck by the glorious playing of the ASQ. They offer rapt concentration and heartfelt intensity. It leaves a powerful impression.

The final work of the complete set is the Quartet No. 16, Op. 135. Lasting just under 25 minutes it never attempts to plumb the great emotional depths of the other late quartets. The opening movement Allegretto is splendidly played with the ASQ maintaining the prevailing pensive and rather gloomy mood. By contrast the Scherzo is performed with fiery petulant tone and jarring and syncopated rhythms.

I found the sound quality of this to be immediate and crystal clear. It is a pity that the comparative dryness of the recording inevitably means that some instrumental tone colour is lost. Closely recorded, the balance fits splendidly into the sound picture.

Of the rival versions the most satisfying sound to satisfy my ideal is from Quatuor Mosaïques on Naïve. The Mosaïques also have the advantage in performing on warmly recorded gloriously rich-toned authentic instruments fitted with gut strings and period bows. On Arte Nova the Henschel with their magnificent instruments in modern set-ups provide appealingly clear, slightly warm and well balanced sonics. Of the other accounts with modern strings and bows the Borodins on Chandos are warmly recorded and decently balanced as are the Italian Quartet on Philips on their digitally remastered analogue accounts. I would describe the Emersons on Deutsche Grammophon and the Alban Berg Quartet on EMI as reasonably clear and well balanced. By contrast I was also impressed with the ice cool, vividly clear and well balanced sound from the Takács on Decca. Of the historical performances the mono accounts from the Busch Quartet on EMI have been digitally remastered to a standard exceptional for their age. Obviously a stumbling block for many, the mono sound is clearly no match for modern digital recordings.

To summarise: the ASQ provide a most natural feel to their interpretations. I admired their splendidly matched phrasing together with an intuitive grasp of structure. The dynamics are rarely overstated and their choice of tempi feels just right. The exceptionally clear and dry sound is closely caught. I loved the quite exceptional essays from musicologist Eric Bromberger. These add appeal to the overall presentation. The ASQ can take considerable credit from these superb interpretations. Their dedication and insight has paid off as this set is one of the very finest available. The Takács on Decca are now no longer clear first choice in the catalogue. This Foghorn set is unquestionably one of my ‘Records of the Year’ for 2009.

-- Michael Cookson, MusicWeb International

Brahms: The String Quintets & Sextets / Alexander String Quartet

BRAHMS String Sextets Nos. 1 1 and 2 1. String Quintets Nos. 1 2 and 2 2 • Alexander Str Qrt; 1,2 Toby Appel (va); 1 David Requiro (vc) • FOGHORN 2012 (2 CDs: 130:33)

Completed in 1860, the first of Brahms’s two sextets is an effusive outpouring of youthful ardor that belies the age and life-experience of the 27-year-old composer who wrote it. By 1860, Brahms had already lived through the harrowing events of Schumann’s attempted suicide, commitment to a mental institution, and premature death, not to mention the effects of those events on Clara and her children. But Brahms was also in love with Clara, or at least with some idealized love surrogate for Clara, and this B?-Major Sextet seems to sing a song of blissful, sun-filled days, until the arrival of the second movement, that is—a set of variations in D Minor on a theme strongly redolent of the Gypsy melos Brahms picked up during his tour with Hungarian violinist Ede Reményi and which would infuse much of his music for the rest of his life.

Perhaps the most amazing aspect of this Sextet is the clarity of the textures and lines Brahms maintains throughout the work, in spite of the addition of two more instruments to the ensemble and the thickness of the scoring. It’s a transparency that can be heard with penetrating purity in this performance by the Alexander Quartet in which Tony Appel takes the first viola part, and David Requiro takes the second cello part.

Four years later, Brahms turned his attention to a second sextet, this time in G Major, completing it in 1865. Throughout its composition, Brahms was involved in the most serious romantic dalliance of his life, one that very nearly led to the marriage altar. The woman was Agathe von Siebold, to whom Brahms had proposed. Then, suddenly, Brahms got cold feet and broke off the engagement. What this has to do with the Sextet is that it contains one of the composer’s rare (perhaps only) use of a musical cryptogram in which bars 162–168 of the first movement contain the notes A-G-A-D-H (B)-E, a reference to Agathe.

The G-Major Sextet is also richly melodic, but tinged perhaps with just a bit of wistful nostalgia and regret; at 32, Brahms is becoming the sorrowful, lonely traveler we know from many of his later works. The minor-key Scherzo, which now comes in second place, and the Poco Adagio which follows it, have a certain portentous gravitas about them, as if Brahms now knows the journey going forward will not be a particularly happy one for him.

Toby Appel and David Requiro switch roles for the G-Major Sextet, with Appel playing second viola and Requiro playing first cello. The effect on the ensemble is a darkening one, which suits the music perfectly. Go-to, long-time favorites in this piece have been the Nash Ensemble on Onyx and the Raphael Ensemble on Hyperion, but once again, the Alexander Quartet, joined by Appel and Requiro, makes a most persuasive case for the score with a tonal refulgence, textural translucence, and expressivity of phrasing that are hard to resist.

Much later in Brahms’s output come the two string quintets. The F-Major was written in 1882 at Bad Ischl, the composer’s favorite summer retreat. The normally highly self-critical Brahms was so pleased with the work that he wrote to his publisher, “You have never had such a beautiful work from me,” and in a letter to Clara Schumann, he called it “one of my finest works.” History has not necessarily concurred, if one judges by the number of recordings the piece has received; at around 30, it would seem to be Brahms’s least popular chamber work. Hearing it, one has to wonder why, for it contains some of the composer’s most haimish music, warm, sun-drenched, and filled with the optimism and promise borne by a spring day. Unusual for Brahms’s larger chamber works as well is the fact that the Quintet is in three movements instead of four, with the second movement combining elements of a slow movement and a Scherzo into one.

I first learned the quintets from the 1970s LP recordings by the Guarneri Quartet with Michael Tree, which I reviewed in their digitized transfers in 32:6. The players bring a great deal of warmth and bigheartedness to their readings, but they’re perhaps not quite as technically polished as are the Boston Symphony Chamber Players on a Nonesuch CD, which I’ve long enjoyed. I haven’t heard the Uppsala Chamber Soloists’ recent entry on Daphne, which Lynn Bayley praised highly in 37:1, but of those I am familiar with—and in addition to the above-cited Guarneri and Boston versions, they include the Juilliard Quartet with Walter Trampler and the Hagen Quartet with Gérard Caussé—I’d have to say that the Alexander Quartet with Tony Appel outshines them all. The readings are closest to the classic Guarneri accounts in their warmth and beauteous sound, but more technically polished, better balanced, and offering more detailed recorded sound.

The same may be said of the G-Major Quintet, op. 111, the work Brahms intended to be his last, but as we know, Fate had other plans for him. The Quintet was composed in 1890, again at Bad Ischl, as the previous Quintet had been. Surprisingly, there’s no sense of leave-taking, nothing autumnal in the character of this music. It’s in fact quite joyful. In certain ways, however, it does sum up the totality of Brahms’s art. It has been called the composer’s most cosmopolitan work, suggesting a diversity of Italian, Viennese, Hungarian, and Slavic influences. The score has an almost serenade-like personality to it, reflecting back on Brahms’s early orchestral serenades.

These are performances to fall in love with and to live with happily ever after.

FANFARE: Jerry Dubins

Brahms: Complete Quartets for Strings / Alexander String Quartet

The Alexander String Quartet launches its 40th season with this recording of Brahms String Quartets — plus Brahms’ Intermezzo (transcribed for string quartet by Zakarias Grafilo). With these complete Brahms quartets, the ASQ has compiled a veritable Brahms compendium, including Brahms’ Clarinet Quintets (FCL 2021, with Eli Eban) and Piano Quintets (FCL 2014, with Joyce Yang), both named MusicWeb International Recordings of the Year, as well as his String Quintets and Sextets (FCL 2012), which were hailed as a “life-enhancing set” by The Arts Desk. The Alexander String Quartet was formed in New York City in 1981 and captured international attention as the first American quartet to win the London International String Quartet Competition in 1985. The quartet has received honorary degrees from Allegheny College and St. Lawrence University, and Presidential medals from Baruch College (CUNY). The Alexander String Quartet is a major artistic presence in its home base of San Francisco, serving since 1989 as Ensemble in Residence for San Francisco Performances and Directors of the Instructional Program for the Morrison Chamber Music Center in the College of Liberal and Creative Arts at San Francisco State University.

Bartok & Kodaly: The Complete String Quartets

BARTÓK String Quartets No. 1–6. KODÁLY String Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 • Alexander Str Qrt • FOGHORN 2009 (3 CDs: 205:55)

This fascinating set combines the string quartets of two then-young professors of music in Hungary, Béla Bartók and Zoltan Kodály. It’s an interesting set even though Bartók wrote a half-dozen quartets, which have since become staples of string quartets around the world, whereas Kodály only wrote two which are not as frequently programmed. Nor are the Kodály quartets as frequently recorded: ArkivMusic lists only one other recording of the First Quartet, by the Kontra Quartet (BIS 564), and only seven other recordings of Kodály’s No. 2, of which three are historical performances (the Végh Quartet, 1951, on Orfeo 316931; the Hungarian Quartet, 1952, on Music & Arts; and the Hollywood String Quartet, 1958, on Testament). Bartók beat Kodály to his First Quartet by a matter of months, the premiere occurring on January 27, 1909. Both composers worked on their second quartets during the harsh period of the First World War, and both works also had their premieres in 1918. For whatever reason, Kodály stopped at this point, whereas Bartók wrote four more quartets.

Comparing the Emerson Quartet’s performances of the First and Third Bartók quartets to the Alexander’s (I really didn’t have time to do the entire set, but these two quartets provide a good basis, the First being from Bartók’s earlier period and the Third coming from 1927), I found interesting if subtle points of comparison. But my Fanfare colleague Art Lange, upon reviewing the Emerson set when it was reissued in 2007, went even further back, comparing it to the performances of the Hungarian Quartet, and noted the earlier group’s “looser, albeit dramatic approach” in which the Hungarians “take a few liberties with pauses and tempos” and “have a better feel for the folk elements,” though—and I stress this—the earlier group tended to lessen “the accumulated tension” and “exaggerate more of the mysterious and atmospheric passages.” This trend, then, is simply turned up a notch in intensity and continuity by the Alexander, bringing us a tad further forward from the folk style that Bartók used.

With the Third Quartet, Bartók’s most astringent, compact, and dense work of the six, the style of playing is virtually identical in the case of both the Emerson and the Alexander: sonorities are lean, attacks are sharp, and the musical contours angular. There aren’t many interpretive options in this particular piece. But in the First Quartet (as well as in the first movement of the Second, which I also compared), there are decided differences in approach and style. The Emerson employs particularly broad tempos in the opening movement of the First Quartet, taking a leisurely 9:16 compared to the Alexander’s 8: 30. There is also greater warmth in the Emerson’s sound: whether this is a condition of their actual timbres or simply advantageous microphone placement, I don’t know. Of course, the leaner, brighter quality of the Alexander’s recording is entirely appropriate to modern music, particularly the modern music that emerged after Bartók’s death, and even within the context of these six quartets their performances set a very high standard.

As an example, I felt that the Alexander’s performance of the First Quartet’s opening movement, though less leisurely in feeling, has a tensile quality that immerses the listener in Bartók’s unique sound world and holds your attention. It is almost as if the Alexander’s players had the entire score in their heads, could “see” the music progressing as one continuous flow from first note to last, and thus propelled it into the ether for the benefit of the microphones. They do not, thankfully, play mechanically, the music being produced with almost explosive energy and drama. Yet if one goes by timings, the evidence is not always in the Emerson’s favor. The Alexander nearly always takes the fast movements just as fast if not faster than the Emerson, whereas their slow movements are generally (but not always) more relaxed, an exception being the Lento Finale of the Second Quartet, which the Emerson explores in 9:18 while the Alexander gets it done in 7: 38. As I say, tempos do not always indicate phrasing, but a performance nearly two minutes shorter simply has to be taken faster. What’s interesting, however, is that by and large the Alexander’s performance only sounds a little faster, and once again it ties this movement into the overall fabric—the continuity—of the Quartet as a whole.

The Alexander also finds moments of repose within their forward momentum; it’s just that their moments of repose are subtler, less easily discernible as pauses in the music (comparing it to literature, one might say commas in the musical sentences). To a large extent, Bartók’s six quartets are the 20th-century equivalent of Beethoven’s late quartets, and one can most certainly make a generalization between the way earlier string quartets such as the Rosé played them—with a certain amount of gemütlich, more portamento than we are used to today, and more astringent string tone due to the musicians’ more frequent (but not constant) use of straight tone—and the way we’ve come to hear them since the days of the Budapest Quartet, surely the first “modern” string quartet in terms of tautness and ensemble virtuosity, and the Yale Quartet, whose 1961 recordings of these thorny works set new standards. We simply can’t go back to the Rosé Quartet and hear their performances of Beethoven as being within our conception of the music; yet both as a quartet leader and as concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic, Arnold Rosé’s artistry and integrity as a musician was utterly beyond question.

I mention this in connection to these performances because it is not only an interesting artistic topic, but also valid in evaluating the evolution of musical performances in the 20th century and beyond. Bartók’s Fourth Quartet, composed in 1928, was in fact dedicated to the Pro Arte Quartet. I daresay that only diehard collectors of vintage performances will be familiar with Pro Arte’s style (they recorded an extensive series of Haydn quartets for HMV in the 1930s, a project ended by the onset of war, and also performed frequently both on and off records with pianist Artur Schnabel), but they were somewhere between the Rosé and the Budapest Quartets. There is a more consistent vibrato, fine and rapid but still discernible, in their playing than in the case of the Rosé, but also a slightly more relaxed rhythmic feel, a bit more give-and-take, than we hear in the playing of the Budapest and the many quartets that followed them. (I should point out that I heard the Hungarian Quartet in person playing Beethoven in 1970, but this was a later edition of this famous group and their style, too, had evolved into a more consistent forward momentum by then, not like their style of the 1950s.)

Checking on the artists’ own website (foghornclassics.com), I was startled to read in a review by Lisa Hirsch of the San Francisco Classical Voice that the Alexander’s live performance of one of the Bartók quartets was “introverted,” without “neglecting the work’s varying moods.” Introverted is not a word I’d apply to these explosive performances. They are indeed fantastic, although I would caution that Bartók’s continual intensity, as well as the extraordinarily dense harmonies and counterpoint, make listening to all six quartets in one sitting a tough go. I would suggest hearing two quartets at a time, separated by either periods of silence or less challenging music. Listening to even three of these works in one session is rather like listening to a full 70-minute CD of Art Tatum. The concentrated complexity of the music that unfolds can tire even a seasoned listener like myself out.

Then we turn to the Kodály quartets, less familiar works surely (this was the first time I had ever heard them), but once again we can make certain generalizations regarding the Alexander’s performances of them as based on the details and style one hears in their Bartók. Even the earlier Quartet No. 1 is given a taut, clean reading, bringing it close in style to Bartók’s own work. Of course, Kodály was his own man: although he assisted Bartók in recording and cataloguing Magyar folk melodies, and used some of their features in his own work, he was more consistent in writing longer, less sharply angular melodies. In short, Kodály’s music sings more, a factor that surely attracted more conductors of his time to perform his music during the 1920s and 1930s than was often Bartók’s fate. In this respect, Kodály’s quartets are a bit closer in general conception (but not exact details) to Janá?ek, whose quartets actually “sing” more than his operas. Listen particularly to the slow movements here: Kodály’s music, and the Alexander’s playing of it, are exceptionally lovely and moving in addition to being musically clean. Once again, as in their Bartók, the Alexander has found a way of bringing out the music’s tender side when tenderness is called for—which is more frequently in these Kodály works.

The list price of this set is $29.96, which breaks down to $9.93 per CD, a very reasonable price in this modern era, but the Alexander’s website indicates that Allegro Music is selling the set for $23.97 (which you can order directly from them), which breaks down to $7.99 per disc, bringing it into line with a budget label such as Naxos. I still like the Emerson’s recordings of the Bartók, but as a total package this one is irresistible. If you’ve put off buying a set of the Bartók quartets until now, and/or don’t have any recordings of the Kodály, you can’t go wrong with this collection. It is, quite simply, terrific.

FANFARE: Lynn René Bayley

Apotheosis, Vol. 2: Mozart Piano Quartets / Yang, Alexander String Quartet

Maintaining focus on Mozart’s last years, members of the Alexander String Quartet join with electrifying and much-lauded pianist Joyce Yang on this recording of the two piano quartets. This is the second of a three-volume set which will include many of Mozart’s great chamber works from that period. Eric Bromberger’s liner notes contextualize these works within the canon: “Some have claimed that Mozart invented the piano quartet, but he did not. Other composers- including the fourteen year old Beethoven- had written quartets for piano and strings earlier, but Mozart was the first to face squarely the challenges of this difficult form, and he wrote the first two great piano quartets.” Now in its 37th season, the Alexander String Quartet’s discography includes major cycles by Bartok, Kodaly, Mozart, Shostakovich, and Beethoven. ASQ is also an important advocate of new music, with over 35 commissions and premieres. In addition to extensive concertizing on five continents, the quartet is on the faculty of San Francisco State University where they direct the Instructional Program of the Morrison Chamber Music Center. They have been feted as Ensemble in Residence with San Francisco Performances for more than a quartet century and at the Mondavi Center at UC Davis for 15 years.

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}