Halle

66 products

-

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleSibelius: Symphonies Nos. 5, 7 & En Saga / Elder

This exhilarating album contains stunning live symphonic performances of works by Jean Sibelius (1865-1957). Included in this recording are his Symphony No....

$20.99April 08, 2016 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleShostakovich: Symphony No 5, Etc / Skrowaczewski

This is an Enhanced CD, which contains both regular audio tracks and multimedia computer files.

$20.99September 01, 2008 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleIreland: A London Overture / Wilson, Halle Orchestra

Currently there seems to be no stopping the resurgence of interest in John Ireland's music. His cause is certainly being helped by...

$20.99June 01, 2009 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleHolst: The Hymn Of Jesus; Delius: Sea Drift & Cynara

Following unparalleled success with recordings for orchestra and choir, including awards in recent years from both Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine, the...

$20.99September 01, 2013 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleEnglish Spring / Mark Elder, Halle Orchestra

A marvellous disc of unjustly neglected English music, superbly played. The planning behind this disc shows not only enterprise but also great...

$20.99April 01, 2011 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleEnglish Rhapsody - Delius & Butterworth / Elder, Halle Orchestra, Et Al

This is an Enhanced CD, which contains both regular audio tracks and multimedia computer files.

$20.99September 01, 2008 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleEnglish Classics

A double width case houses this 4 CD anthology of English classics reissued from individual discs that have appeared over the last...

$37.99September 01, 2011 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: Wand of Youth Suites Nos. 1 & 2, Nursery Suite, Etc / Elder, Halle

The sound is exemplary in clarity, warmth, and balance. None of this is “great” music but committed Elgarians will relish the delicacy...

$20.99November 02, 2018 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: Violin Concerto, The Kingdom Overture, Dream Of Gerontius Prelude / Elder, Halle Orchestra

Another major recording of this glorious concerto: Zehetmair, on top form, gets the partners of one's dreams in the Hallé with its...

$20.99February 01, 2010 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: The Kingdom / Sir Mark Elder, Halle Choir And Orchestra

In 1968, to celebrate his forthcoming 80th birthday the following year, Sir Adrian Boult was given by EMI the choice of a...

$32.99October 01, 2010 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: The Dream Of Gerontius Op. 38 / Elder, Groves, Terfel, Coote, Et Al

A remarkable achievement. Last year, when I surveyed most of the available recordings of The Dream of Gerontius, I expressed the hope...

$32.99October 01, 2008 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: The Apostles / Imbrailo, Groves, Coote, Elder, Halle Orchestra

BBC Music Magazine: Recording of the Year and Choral Winner of the year: 2013. Performed beautifully. Everyone is on quite spectacular form....

$32.99September 01, 2012 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleElgar: Sea Pictures, Polonia & Pomp and Circumstances Marches / Halle

The latest release in Hallé’s award winning Elgar Edition features the much anticipated studio recording of Sea Pictures, coupled with the lesser...

$20.99March 11, 2016 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Halle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

HalleVaughan Williams: Symphonies Nos. 7 & 9 / Elder, Hallé

Premiered by the Hallé under Sir John Barbirolli in 1953, the Sinfonia antartica originated in Vaughan Williams’ score for the film ‘Scott...

$20.99June 03, 2022 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleHalle

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

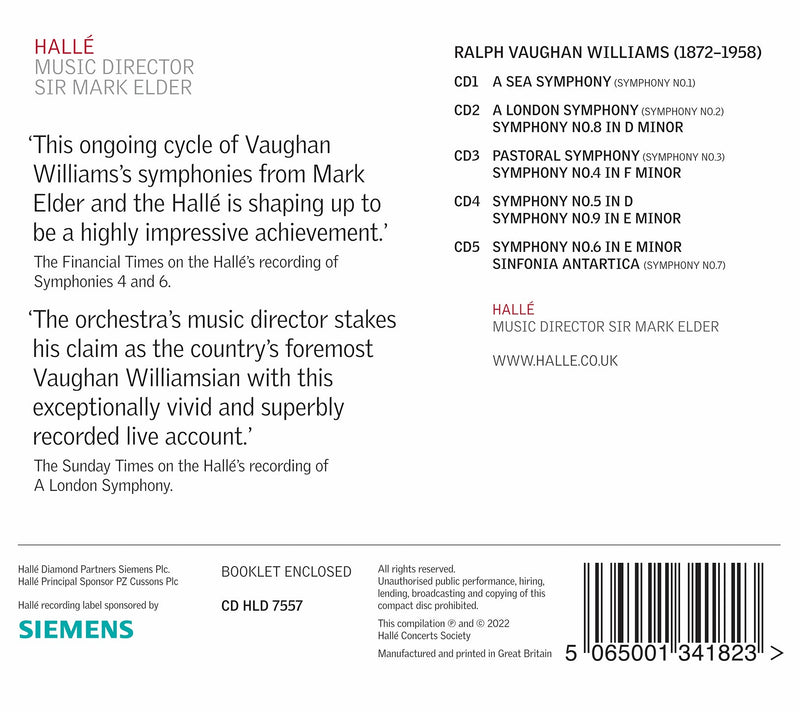

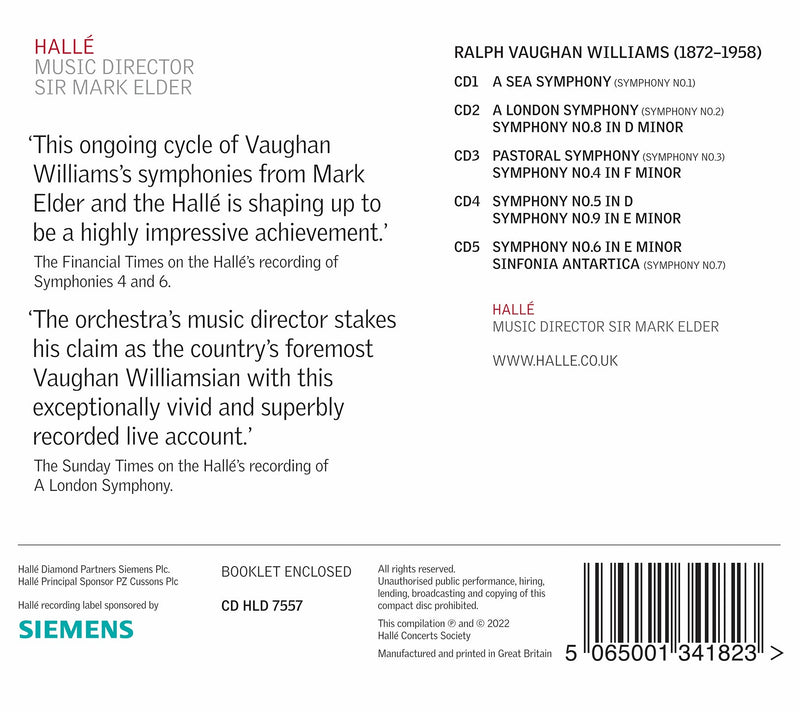

On SaleHalleVaughan Williams: The Complete Symphonies / Elder, Hallé

This boxed set includes all nine Vaughan Williams symphonies, attractively packaged and released at a special price to mark the occasion of...

June 03, 2022$69.99$52.99

Sibelius: Symphonies Nos. 5, 7 & En Saga / Elder

“...raw, massive, glacial, thrilling. Elder and the Halle have a strong track record in this repertoire.” - The Observer

Shostakovich: Symphony No 5, Etc / Skrowaczewski

This is an Enhanced CD, which contains both regular audio tracks and multimedia computer files.

Ireland: A London Overture / Wilson, Halle Orchestra

Currently there seems to be no stopping the resurgence of interest in John Ireland's music. His cause is certainly being helped by a number of new and reissued recordings, a splendid biography The Music of John Ireland by Fiona Richards (2000) and the hard work by the John Ireland Charitable Trust.

It is not difficult to imagine a wry and knowing smile of satisfaction on the face of Ireland's great teacher Sir Charles Stanford. Although their relationship was often fraught and his teacher's methods considered harsh the influential Stanford loved to see his pupils having success. Ireland certainly came a long way from his days as a vulnerable young student at the Royal College of Music (1897-1901). An easy target for ridicule by attending his early classes wearing knickerbockers and boots; goodness knows what psychological damage he was caused. In 1898 the great master Stanford said to his young pupil, 'All water and Brahms me bhoy and more water than Brahms …Study some Dvořák for a bit and bring me something that isn't like Brahms' ('Charles Villiers Stanford' by Paul Rodmell, Ashgate 2002). Stanford's rebuke seemingly did the trick and Ireland soon produced his precocious and charming Sextet for clarinet, horn and string quartet.

The opening track of this Hallé label disc is the symphonic rhapsody Mai-Dun that Ireland completed in 1921. It seems that the score was inspired by Maiden Castle, the Iron Age hill fort, a structure that reflected Ireland's great interest in historic sites such as fortifications and pagan burial sites. Throughout one is aware of the variegated nature of the score alternating the serious nature of war with calmer passages representing peace.

The tone poem The Forgotten Rite was composed in 1913/14. The work is a product of Ireland's interest in the archaeological sites on the island of Jersey and his fascination with the Arcadian vision of the Greek God Pan. A strong undercurrent is the sense of mystery and one can easily imagine the scene of dawn breaking over a stormy seascape.

The inspiration for the orchestral overture Satyricon from 1944/46 was literary. The character of the boy Giton from the 'Satyricon' of Petronius Arbiter appealed strongly to Ireland. I enjoyed the energetic and effervescent rhythms that at times seemed distinctly Bernsteinesque. With shimmering and soaring string melodies of increasing intensity Ireland inhabits a soundworld close to that of say Max Steiner's score to Victor Fleming's Hollywood blockbuster Gone with the Wind (1939). I loved the strong bucolic feel of the solo passage for clarinet followed by the flute at 4:01-4:57.

Also in the year 1946 Ireland was commissioned to write the score to the film The Overlanders. The Harry Watt film recounted the hazardous journey of driving cattle across the vast country of Australia. John Wilson conducts the five movement suite prepared by Sir Charles Mackerras and published in 1971. I was reminded of the suitability of Ireland's music to Baz Luhrmann's film Australia the 2008 epic romance starring Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman which shares an uncannily similar plot to that of The Overlanders. In particular I enjoyed the third movement Intermezzo: Open Country which is convincingly evocative of Jackaroos on horseback driving herds of cattle across the Australian bush.

In the manner of Elgar's Cockaigne Overture (In London Town) and Vaughan Williams' A London Symphony Ireland was inspired by the sights and sounds of London to write an orchestral score. His A London Overture (1936) is a reworking of the earlier Comedy Overture from 1934 scored for brass band. With music that never reaches anywhere close to the heights of Elgar and Vaughan Williams, Ireland's moderately convincing score seems to lose its way especially in the middle section.

In 1942 Ireland was commissioned by the British Ministry of Information to write a morale boosting patriotic score; the Epic March was the result. It seems that the score contains several musical references to various personalities that were significant in Ireland's life. At times in the Epic March I heard slight reminders of the Walford Davies/George Dyson RAF March Past. Despite the enthusiastic promptings of conductor John Wilson the Epic March, although agreeable, only revealed to me its lacklustre quality.

The music of John Ireland is served extremely well by John Wilson and the Hallé who are on splendid form. These engaging and refreshing readings serve to reinforce to me how far the orchestra has come in recent years. The sound quality from Studio 7 at the BBC at Oxford Road, Manchester is a credit to the engineers. Fiona Richards's booklet notes are as authoritative as I had expected.

-- Michael Cookson, MusicWeb International

Holst: The Hymn Of Jesus; Delius: Sea Drift & Cynara

English Spring / Mark Elder, Halle Orchestra

The planning behind this disc shows not only enterprise but also great imagination. Here we have four very different responses to Spring from three English composers.

Bax’s Spring Fire is a great rarity. Indeed, in his recent very wide ranging interview with Michael Cookson, Sir Mark Elder says he knows he is the only conductor who currently performs the work – because he’s in possession of the only set of parts! Earlier in his conversation with Michael, he refers to the work as “a masterpiece, a huge orchestral piece.” That belief in the quality of the score shines out in this very fine live performance. For all its rarity, the piece has had a previous recording, by that other doughty champion of English music, Vernon Handley. That was made in 1986 (CHAN 8464) and the coupling is more Bax, though I think Elder’s programme is the more interesting.

Spring Fire dates from 1913 and is cast in five movements, which play continuously – though, as Lewis Foreman points out in his note for the Handley recording, at one point Bax thought of combining the first two movements. The piece is fascinating and often full-blooded, though the opening movement, ‘In the Forest before Dawn’, is gorgeously languid. As Spring Fire unfolds the orchestration is increasingly colourful, detailed and brilliant. The depiction of sunrise, just before the end of the second movement, may not be as expansive or extended as in Daphnis et Chloé but it has, perhaps, more pagan exaltation. The third movement, ‘Full Day’, is hedonistic and exuberant. Here especially Elder’s Hallé brings Bax’s rich scoring excitingly to life though these excellent players are just as convincing in the more delicately scored passages, in which at times a solo quartet of violins features. A slow, sultry passage leads to the penultimate movement, ‘Woodland Love (Romance)’. We’re told in the useful booklet notes that the score is marked ‘romantic and glowing’, followed by ‘drowsily’. That’s just how the music sounds here. This spacious, erotically charged music is superbly realised by Elder; the playing has delicacy and refinement and the various solos are delivered excellently. The final movement is entitled ‘Maenads’ after the female followers of Dionysus. The music is headlong, riotously colourful and celebratory. The orchestra really gets hold of the piece and the brass and percussion in particular have a field day. It’s good to hear such a rare piece receiving warm applause from the Mancunian audience but the quality of the performance, which is captured in vivid sound, more than justifies the reception.

Another rarity is Idylle de Printemps by Delius, one of his earlier works. According to Calum MacDonald’s notes, the piece was scarcely heard in the composer’s lifetime and even less so thereafter until the 1990s. This is rather odd since apparently Beecham owned the autograph score for many years. Did he play it and, if not, why not? It’s not a work that I can recall coming across much – if at all – in the past but it’s well worth hearing. As it says in the notes, “the mood is contemplative, taking delight in a sense of the natural world.” The Hallé plays it marvellously, combining warmth and finesse. Incidentally, though this is also a live recording there is no applause afterwards. I hope that this fine new recording will help to establish the piece, for that it what it deserves.

The March of Spring is a much more mature work in every sense. It is the last of the four movements that comprise North Country Sketches and the music shows the composer’s delight at the reviving return of Spring. Sir Mark and his excellent orchestra bring out all the detail of the score in a very fine performance. The use of the word ‘march’ in the title is a bit of a misnomer, though there’s a brief, slightly martial episode a couple of minutes from the end. What Delius has written is more of a celebration of nature and the new life of Spring. It would be good to hear Elder in the complete North Country Sketches.

Frank Bridge’s Enter Spring is not exactly standard repertoire either. If memory serves me right Elder and the Hallé gave this work at the 2010 BBC Proms, which would have been a few weeks after this recording was made. It’s a fairly late work by Bridge and so it comes from the period, after the First World War, when his work had become influenced by some of the more advanced European composers and had become much more adventurous and harmonically unstable. It was commissioned for the 1927 Norwich Festival and I was surprised to learn from Calum MacDonald’s outstanding note on the piece that this was the first – and only – time that Bridge received a commission for an orchestral work. Mr MacDonald relates that the audience for the first performance included the young Benjamin Britten, who was so impressed by what he heard that he resolved to become Bridge’s pupil. Britten said that he was impressed by the work’s ‘riot of colour and harmony’ and so can we be in this splendid Hallé performance. I know of three previous recordings, all of which I admire very much. There’s the 2000 recording by Richard Hickox, part of his Chandos series of Bridge orchestral music. There’s also what was the pioneering account – in the sense that it was the first to be issued – by Sir Charles Groves, which was made in 1975. Most interesting of all, in many ways, is the live account conducted by Benjamin Britten in 1967, forty years after he attended that première. According to the notes with the present disc, the Britten performance represented the revival of the work; it had not been played for thirty-five years. Britten’s reading was issued in 1999 by BBC Legends (BBCB 8007-2). I fear that will be long deleted but if you ever track down a copy, snap it up for the performance and, indeed, the entire content of the disc, is well worth hearing.

It’s quite a while since I listened to Enter Spring and I was very interested to note the disparity between the various conductors in terms of the time each takes to play the score. Groves is the most expansive, taking 21:22. Hickox and Britten are significantly swifter overall at 18:36 and 19:44 respectively. Elder is closer to Groves at 20:50. I must say, while in no way disparaging the considerable merits of his rivals, that I admire Elder’s way with the score enormously. His is an expansive but not indulgent reading. He’s particularly successful, I think, in balancing the often teeming detail of the score – and credit for that must also go to the engineers. The Hallé’s playing is absolutely superb. I think this is now the finest account of this important score that I know; Bridge’s prodigious invention and great originality is revealed by a highly sympathetic interpreter and a top flight orchestra.

This is a marvellous disc. The repertoire is unusual but fully deserving of the public’s attention. Sir Mark Elder has already attracted many plaudits for his advocacy of English music but, if I may say so, it’s great to see him prepared to venture quite far off the beaten track. Music such as is contained on this disc isn’t desperately fashionable but its neglect is unjustified, as performances of this calibre show. I hope that Elder will undertake more works by these three composers for advocacy such as this can only further the cause of their music.

-- John Quinn, MusicWeb International

English Rhapsody - Delius & Butterworth / Elder, Halle Orchestra, Et Al

This is an Enhanced CD, which contains both regular audio tracks and multimedia computer files.

English Classics

The CD 1 (English Rhapsody CDHLL7503) Butterworth items are lovingly and most affectingly paced and weighted. Listen to the second phrase in A Shropshire Lad. No need for embarrassment in the company of Barbirolli or Boult. The Delius items are similarly successful with Elder switching to elusive languid melancholy and ecstasy. Brigg Fair is helpfully tracked into five segments. Then Hallé do something unusual – they add the Grainger setting of Brigg Fair by the Hallé Choir with James Gilchrist as the exposed tenor soloist. Gilchrist is outstanding but the choir’s close-up rough textures grate slightly. The last item is another Brigg Fair reference with the folk singer, the 75 year old, Joseph Taylor heard in a 1908 recording.

CD 2 (English Rhapsody CDHLL7512) starts with another classic essayed by one of Elder’s predecessors in Manchester, Barbirolli – Bax’s Tintagel. Fellow reviewer, Em Marshall did not warm to this disc. For my part I found it very satisfying; each to his or her own. The Tintagel is tautly done with some very sharply delineated effects adding to the romantic sweep and tension of the piece. I certainly prefer it over Boult’s Lyrita reading though not over the supple Barbirolli and the stormily driven Bostock and Goossens. The Lark Ascending is pretty cool and I too found it unengaging. By contrast the Norfolk Rhapsody No. 1 works rather well and the analytical recording complements the mystery of the music. The Finzi was taken at a brisk pace but is a success. The Delius pieces, especially the second, have a lambent glow. Then more from the Hallé Choir who sound in warmer voice and gleamingly resolved tone.

I reviewed English Spring earlier this year. It is reproduced on CD 3. The concert-live Bax Spring Fire is the single longest piece in this collection. I recall listening to the whole CD several times over on a long journey. I found it then and still find it a fine interpretation with exemplary recording engineering to match. The other spring pieces are just as good. The salon-inflected Idylle spins a really memorable melody with expert hands – early Delius unlike the fully mature movement from North Country Sketches – which I always think of as Delius for people who think they don’t like Delius. The Bridge is a masterpiece and no mistake and compares very favourably with versions by Groves, Hickox, Judd, Marriner and the meritorious and unfairly overlooked John Carewe (Pearl SHECD9601).

The last disc has its programme culled from a variety of discs. The label, Hallé and Elder have squared up to the Elgar legacy in a major way with only The Apostles now outstanding. Their Elgar list is ample: Elgar portrait; Symphony 1; Symphony 2; Enigma; Violin Concerto; Cello Concerto and Falstaff; Gerontius and The Kingdom. Elder’s Cockaigne is recorded with wonderfully textural clarity and thudding impact. The beguiling innocence of Dream Children is wondrously done as is the lightly and elegantly sighing Serenade where rather like Cockaigne Elder is up against Barbirolli’s iconic recordings. It’s all most touchingly done. The RVW Wasps Overture is well enough done and buzzes and sings well. The Act II Entr’Acte has a few Straussian moments. Then another march – this time a gawky one in the March Past of the Witnesses. The music is magically imaginative – try tr.10: the Act III Entr’Acte. Exit Elder – enter Wilson currently the darling of the Broadway musical and Big Band revival cadre (That’s Entertainment) with highly effective and street-sharp Bond and Sondheim Proms resounding to his credit. His John Ireland is brilliant but the mystery of The Forgotten Rite does not come across as it does with Boult (Lyrita) and Thomson (Chandos). The untypical but still splendid Epic March is much more effective. This is the splendid British march mantle worn and stepped out with complete aplomb. The character is more bitterly warlike than usual with a touch of Elgar P&C4 and Bliss’s Things to Come.

Determination and nobility. The liner notes are assembled from the original issues.

This sheaf of anthologies is satisfying. The recording quality is uniformly good with some very fine readings along the way. These are not always the very best in the catalogue but nothing here disappoints. A much better than worthy introduction to English music of the first half of last century.

-- Rob Barnett, MusicWeb International

Elgar: Wand of Youth Suites Nos. 1 & 2, Nursery Suite, Etc / Elder, Halle

Miniatures though they be, the two Wand of Youth suites are not just “light” music, in that there is much here which is – charming, yes, but also emotionally deeply evocative and musically profound. Their quality has attracted recordings from celebrated conductors such as Boult, Handley, Mackerras, Bryden Thomas and van Beinum, to name but a few; now Mark Elder includes them in his series of Elgar works with the Hallé, which has hitherto garnered much critical acclaim – my own favourite recordings of the symphonies are Elder’s.

These works were based on material written by Elgar many years before as a teenager as accompaniment to a play, reworked by the composer as a man of fifty while simultaneously composing his First Symphony - so they presumably provided some relief from that arduous task. They are characteristically innocent and nostalgic, evoking an idealised fairyland free from adult taint; both were dedicated to friends, as was Elgar’s custom, most famously in the Enigma Variations.

The variety of orchestral colour and melodic invention mark these suites out as typical of the composer; the Overture of the first suite starts with a bustling motif played with great brio followed by a falling Seventh –a motif very recognisably Elgarian. A gentle “Serenade”, an elegant parody of a Handelian minuet, a shimmering, Mendelssohnian “Sun Dance” ending in a blaze of brass encompass so many of the tropes we know from the more famous works while also paying homage to Elgar’s predecessors; while the string passage is all Elgar, if the sinuous clarinet motif at the heart of the “Fairy Pipers” isn’t at least unconsciously inspired by Tchaikovsky’s “Arabian Dance” from the Nutcracker, I have no ears.

The pattern of great thematic and colourific variety continues into the second suite, although I do not find it quite as uniformly captivating as the first. Elgar introduces a glockenspiel into the “The Little Bells”, employs graceful arabesques to suggest the flow of water in “Fountain Dance” and creates two contrasting bear portraits, the first melancholy, `the second rumbustious; Elder and the Hallé successfully capture all these moods.

The Nursery Suite was Elgar’s final foray into mining his juvenilia: it is more, lovely, pastoral music, including an extended solo for flute in The Serious Doll, played with assured, liquid musicality by Katherine Baker. Likewise, Lyn Fletcher plays a fine violin solo in the final movement, Envoy (Coda). The Wagon (Passes) was encored at its premiere at the request of the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King George VI and Queen Elizabeth). Dreaming has one of those long, languorous melodies we know from the symphonies.

Bonus “lollipops” are provided in the form of the lush, orchestrated versions of Salut d’amour and Chanson de nuit, both so delightfully sentimental and redolent of the Edwardian drawing room, beautifully played.

The sound is exemplary in clarity, warmth, and balance. None of this is “great” music but committed Elgarians will relish the delicacy and sensibility of Elder’s performance.

– MusicWeb International (Ralph Moore)

Elgar: Violin Concerto, The Kingdom Overture, Dream Of Gerontius Prelude / Elder, Halle Orchestra

Another major recording of this glorious concerto: Zehetmair, on top form, gets the partners of one's dreams in the Hallé with its great Elgar tradition.

Elgar: The Kingdom / Sir Mark Elder, Halle Choir And Orchestra

Boult was a great admirer of The Kingdom and in a note accompanying the original release of his recording he included the following statement:

“I think there is a great deal in The Kingdom that is more than a match for Gerontius, and I feel that it is a much more balanced work and throughout maintains a stream of glorious music whereas Gerontius has its up and downs. Perhaps I was prejudiced by hearing a great friend of Elgar’s [Frank Schuster] (who was very kind to me in my young days) jump down the throat of a young man who made this criticism [that Gerontius was a finer achievement than Kingdom]: ‘My dear boy, beside The Kingdom, Gerontius is the work of a raw amateur’.”

I wouldn’t go as far as Schuster but I know what Boult meant about Kingdom being a morebalanced work - perhaps because Elgar fashioned his own libretto. Also, I believe that by the time he composed Kingdom, six years on from Gerontius, Elgar had become an even more accomplished orchestrator and a more assured choral writer.

Boult’s version, though now starting to show its age sonically, remains a benchmark. Since it appeared there have been two more recordings. One was a sumptuously engineered Chandos set from Richard Hickox (CHAN 8788/9). The other, which I have not heard, was made for RCA Red Seal by Leonard Slatkin but I suspect is no longer available. Sadly, that fine Elgar conductor, Vernon Handley, never had the opportunity to record the work.

Every since I reviewed his superb recording of Gerontius I have been hoping that Sir Mark Elder might make a recording of Kingdom and now, here it is. Unlike his Gerontius, which was recorded under studio conditions, this is taken from a single live concert performance. ‘Live’ recordings often include a few edits from rehearsal. I don’t know if that happened here but if it did the edits are completely undetectable and, in fact, I’m pretty sure that what we have here is a single, unedited performance; that’s what it sounds like. Those who worry about applause on CDs can be reassured; unlike Elder’s recent recording of Götterdämmerung applause is absent here.

One thing I should say at the start is that if you buy this recording for no other reason - and there are many reasons why you should buy it - do so in order to hear the orchestral playing. That may be an odd thing to say about a choral recording and in saying it I do not mean in any way to disparage the vocal contributions. However, when Elgar wrote The Kingdom he was at the height of his very considerable powers as an orchestrator and his colourful and resourceful orchestral scoring is a major element of this score. I think the composer would have rejoiced to hear his music so magnificently played as it is here by the Hallé. Their playing is truly world class and a vivid testament to the achievement to date of their Music Director, Sir Mark Elder. The playing radiates assurance and a familiarity with Elgar’s idiom. The strings consistently play with richness and flexibility while the woodwind has great finesse. Best of all, the brass section possesses splendid power and authority but, schooled by Elder, this is never overdone. One small example will suffice. Towards the end of Part III, beginning five bars after cue 120 in the Novello score, the brass nobly play the ‘New Faith’ motif (CD 1, track 9, 4:25). In the Hickox recording this is delivered fortissimo and it’s rather grandiose as a result. Elder, like Boult, has noticed that the marking is only forte and the consequent restraint in both recordings is more effective.

The LPO plays excellently for Boult on his recording while the LSO is on refulgent form for Hickox. However, I feel that the Hallé surpass both their rivals. They may not be recorded as vividly as the LSO - I’ll comment about the respective recordings later - but they are no less impressive. Also, I feel that Hickox has a tendency to underline points in the score. This rather impedes the natural flow of the orchestral playing in a way that is absent from either Boult’s or Elder’s performances though both of these conductors - and their respective players - consistently display admirable attention to Elgar’s copious markings.

The Hallé Choir is by no means put in the shade by their orchestral colleagues. From the very start they sing with great confidence and impressive tone. It’s evident that they’ve been scrupulously prepared by their guest Director, Tom Seligman. I particularly appreciated the dynamic range of their singing. They are capable of producing very exciting loud singing where Elgar requires it but their quiet singing is just as noteworthy. The precision and attack that they bring to the music is excellent throughout, as is the clarity of their diction and altogether I think the choir’s contribution is top-class.

The four soloists take respectively the roles of the Blessed Virgin Mary (soprano), Mary Magdalen (mezzo), St John (tenor) and St Peter (baritone). Of these, it is the role of St Peter that is the most prominent though to the soprano falls the very best music in the whole work, the aria, ‘The sun goeth down’.

The tenor role is not easy to present. It has its dramatic moments but it is primarily lyrical. In fact, I think Elgar portrayed St. John as The Comforter among the Apostles, and certainly as a more reflective character than St Peter. The challenge to the tenor soloist is to sing the role with sufficient impact but without straying into vehemence, which was the main reason why I thought Adrian Thompson was miscast in the role at a Three Choirs Festival concert this summer. Arthur Davies, for Hickox, sings with ringing assurance but, I think, misses some of the humanity for which the role calls. Alexander Young (Boult) is the exemplar in this part and I don’t think John Hudson matches Young. For the most part he sings reliably, though there were a couple of occasions on which he seemed to approach important high notes from below. However, to my ears he doesn’t have the same lyrical grace and ease that Young brought to the music.

The mezzo role of Mary Magdalen is sung by Susan Bickley, who so impressed me in Mahler’s Second Symphony at the Three Choirs Festival this summer. She makes a fine job of this role too, singing with warm tone and great clarity throughout. I’d say she’s as good as the excellent Yvonne Minton (Boult) and I prefer her to Felicity Palmer (Hickox). She blends well with Clare Rutter in the fresh, lightly scored duet that forms Part II of the work. Later, she has a couple of very important narrative passages. One such is at the start of Part III (“And suddenly, there came from heaven”). Here she’s dramatic and exciting, rising to a thrilling top G sharp. Further on in the work, she’s just as involving in the narration at the start of ‘The Arrest’ (Disc 2, track 3).

That narration ushers in the great soprano aria, ‘The sun goeth down’. This is a huge test for the soprano soloist, who has to begin and end the aria in a mood of prayerful contemplation but must rise to great dramatic heights in the central section. Margaret Price (Boult) is peerless here, setting standards that I’ve never heard matched on disc or live. In the outer sections of the aria her singing is rapt, supported with great sensitivity by Rodney Friend (I think), playing the luminous solo violin part. In the middle of the aria the dramatic fervour that Price brings to the music elevates it to the highest level. I’m afraid Margaret Marshall (Hickox) doesn’t match this accomplishment at all. There are some instances of wayward pitching on sustained notes at the start of the aria and, beside Miss Price, she sounds a bit squally in the central section.

Clare Rutter may not quite equal Margaret Price but she makes a fine job of this aria. I’d have liked her to sing the opening phrases just a little more softly - especially after Lyn Fletcher has prepared the way so beautifully with a lovely account of the violin solo - but overall her delivery of the more inward passages of the aria shows pleasing sensitivity. When the dramatic intensity of the music picks up she responds with very committed singing. At cue 159 (“The Gospel of the Kingdom”) (disc 2, track 4, 4:55) she’s really fervent yet within a few moments she’s fined things down to produce an exquisite pianissimo on the word “Jesus” (5:57). This is a distinguished piece of singing, which means that the aria is a high spot, as it should be. This is the most important contribution that Elgar gives to his soprano but elsewhere Miss Rutter’s singing is very good, not least in the afore-mentioned duet with Susan Bickley.

The key solo role in The Kingdom is the baritone part, here entrusted to Iain Paterson. He sings well and with authority. Once again, the Boult recording sets the benchmark for John Shirley-Quirk is quite magnificent in the role, singing with a marvellous combination of controlled intensity and tonal richness. For Hickox, David Wilson-Johnson does very well without surpassing Shirley-Quirk. I enjoyed Iain Paterson’s singing very much. He brings intelligence to the role and, as I’ve already said, authority. His crucial, long solo in Part III, built around the ‘New Faith’ theme, is a cornerstone of the work and Paterson doesn’t disappoint. He delivers this and his other solos with conviction and at every turn his diction is clear.

I had hoped that Sir Mark Elder would prove an authoritative interpreter of The Kingdom and indeed he does. Several things mark out his interpretation. One is an impressive control of pace and structure. That, I suppose, is no surprise given his pedigree as a fine operatic conductor. Another is his attention to detail, respecting Elgar’s copious and vital markings in the score. That, again, should be no surprise to anyone who has heard his previous excellent Elgar recordings. He also demonstrates a great understanding of the score, ensuring that the sentiments it expresses are given their due weight but never letting the music sound sanctimonious. It seemed to me that his choice of tempi was, almost without exception, excellent. Elder displays a mastery of the score that is comparable with Boult’s and he doesn’t indulge in any of the over-emphatic point-making that slightly mar Hickox’s otherwise impressive reading. To cap it all, this is a live recording so we can benefit from the sweep and electricity of the occasion.

I should mention the quality of sound in the respective recordings. The Boult recording was made in Kingsway Hall by Christopher Bishop and Christopher Parker. It’s a very good recording but it is now over forty years old and it hasn’t got the same degree of presence and inner clarity as its two more modern rivals. The Chandos recording for Hickox was made in St Jude’s Church, London by Brian and Ralph Couzens. The sound has great presence, indeed punch, and in many ways it’s a splendid achievement. The sound can be thrilling and, as usual with Chandos, a great deal of detail is revealed. However, playing all three recordings on the same equipment and without adjusting the controls made me think that perhaps the fullness of the Chandos sound was just a bit too much of a good thing at times.

The engineering team behind this new Hallé recording is exactly the same one that produced Elder’s warmly received recording of Götterdämmerung. I haven’t yet had the time to do more than sample that Wagner recording though what I’ve heard has impressed me. I’m certainly very impressed indeed by this new Elgar recording. It seems to me to present a nicely truthful concert hall balance. The soloists are given a properly prominent position in the aural picture without one feeling that they’re artificially close. The choir, though behind the orchestra is reported with presence while the orchestra is in excellent balance with both the choir and the soloists, allowing one to appreciate their superb playing without feeling that the orchestra is too dominant.

It only remains to say that the notes are by the doyen of Elgar commentators, Michael Kennedy, who provides a succinct but completely satisfying note about the work and a good synopsis of the action.

I hope that this fine new recording of The Kingdom will enhance the reputation of this marvellous work. It contains a great deal of quintessential Elgar, not least ‘The sun goeth down’. And much of Part III, from the start of St Peter’s extended aria (‘I have prayed for thee’) to the end of that movement, is top-drawer Elgar. The ending of Part III never fails to move me, especially when it’s done as superbly and convincingly as is the case here. As I said earlier, I might not go as far as Frank Schuster in evaluating the respective merits of Gerontius and Kingdom but I feel that Kingdom has been unfairly in the shadow of Elgar’s earlier choral masterpiece so it’s a cause for rejoicing that this splendid new Hallé account is now available.

Elder has already given us a recording of the Prelude to The Kingdom as a filler to his recording, with Thomas Zehetmair of the Violin Concerto. That was a different performance of the Prelude, set down in 2005. Reviewing the disc William Hedley said that Elder’s account of the Prelude made him want to hear the complete oratorio again. Well, now he can and I hope he’ll enjoy it as much as I have. With this excellent recording Sir Mark Elder further enhances his reputation as the finest Elgar conductor currently before the public. I hope he will go on before too long to give us a much-needed new recording of the companion oratorio, The Apostles. Can I also enter a plea that the Hallé’s evolving Elgar Edition will encompass the shamefully neglected Spirit of England, of which I’m sure Sir Mark would be a fine interpreter?

Sir Adrian Boult’s recording of The Kingdom must retain its place as a reference performance, not least because it has the finest quartet of soloists that I’ve ever heard in the work. However, this new Elder interpretation is a worthy rival and should be heard by all Elgar enthusiasts. It is certainly the pre-eminent digital account.

-- John Quinn, MusicWeb International

Elgar: The Dream Of Gerontius Op. 38 / Elder, Groves, Terfel, Coote, Et Al

Last year, when I surveyed most of the available recordings of The Dream of Gerontius, I expressed the hope that Mark Elder, as he then was, and his Hallé forces might make a commercial recording of the work. That hope was inspired by the remarkable performance that they had given at the 2005 Henry Wood Promenade Concerts, which, as I commented at the time, made a great impression on me. Having re-listened to it more than once in the off-air recording I made, I now feel it was, quite simply, the finest live account of the work that I ever expect to hear. And now, with almost identical forces, the newly-knighted Sir Mark Elder has made a studio recording. It comes too late for the 150th anniversary of Elgar’s birth but instead, and more fittingly, perhaps, it marks the Hallé’s own 150th birthday, which falls this year.

The inevitable question is: has it been worth the wait for this recording? The answer is an unequivocal "yes".

The American tenor, Paul Groves, reprises the role of Gerontius, as I hoped he would. I hadn’t realised it at the time but we learn from the booklet biography that his performance at the 2005 Proms was his debut in the role, which makes his achievement that night all the more remarkable. His greatest virtue of all, it seems to me, is the clarity and ease of his singing. Every note is hit right in the centre and his voice has an exciting and pleasing ring. The top notes are always true and secure. I followed in the score but, frankly, that was superfluous as far as the text is concerned for Groves’ diction is crystal clear – as, indeed, is that of the other soloists and the choirs.

In Part I Elgar sets his tenor a task that is almost impossible. The singer must try to suggest the frailty of a man on his death bed while, at the same time, he must be able to deliver heroic, dramatic passages, such as ‘Sanctus fortis’. Groves is fully equal to the dramatic sections though sometimes he does sound a little too healthy for a dying man. ‘Sanctus fortis’ is a huge test and it’s one that Groves passes with flying colours. He starts it in ringing, forthright voice but later on, just before cue 48 in the vocal score, he shades off the end of the phrase "Parce mihi, Domine" with great sensitivity. In this aria, and frequently during the performance as a whole, he demonstrates prodigious breath control. One example occurs in ‘Sanctus fortis’, where the whole eight-bar phrase, "For the love of Him alone, Holy Church as his creation" is taken in one span, where most tenors take a breath, quite legitimately, after the comma. Later, the first phrase of ‘Take me away’ is one glorious, seamless whole, as it should be but often isn’t. Returning to ‘Sanctus fortis’, there’s a lovely piangendo at cue 53, when the words "Sanctus fortis" are repeated gently by Gerontius, and then the phrase "O Jesu, help" is truly anguished. Groves’ delivery of the climatic "In Thine own agony", top B flat and all, is magnificent. In all, his performance of this testing keynote aria is very fine.

Part II brings different demands for the tenor soloist. Now he represents the soul of the dead Gerontius. Quite a bit of the music in Part I required the vocal resources of a heldentenor but the opening pages of Part II needs the subtlety of a lieder singer. I’m not sure that Groves is quite successful in these passages. The clear, pleasing singing remains a constant feature but he doesn’t seem to delve as deeply into the words as do some of his distinguished predecessors in the role. As an example, I compared the first solo – "I went to sleep" - as sung on disc by John Mitchinson (for Rattle) and by Anthony Rolfe Johnson (Vernon Handley). Both are so much more responsive to the words and both also sing more quietly. Groves can’t quite match those experienced masters of the role. But he brings his own insights and subtleties to the part and his dialogue with the Angel is intelligently and sensitively sung. Inspired, no doubt, by the presence of an audience, he was a touch more spontaneous at times in the live Proms performance. On the other hand, on that occasion he had to project into a huge acoustic. Here, recording under studio conditions, he can offer a more subtly nuanced reading. The last section of the role, the aria ‘Take me away’, is another hugely demanding solo. Groves’ opening is superb. Later on, perhaps, a little more dynamic contrast would have been welcome but his fervour – not overdone - firm tone and excellent breath control offer ample compensation and the final phrase – "there let me be" – is most affecting.

Alice Coote, who was the Angel in the Proms performance, once again takes the role for the recording. Like Paul Groves she offers much but I found it interesting to compare this performance with her live account. To my ears her voice has a slight edge to it at times in this present performance and her tone doesn’t have quite the same degree of warmth and fullness that she exhibited at the Proms. That said, she is right inside the role, she sings with feeling and commitment and her performance gives a great deal of pleasure. I like, for example, the inflection she brings to the words, "this child of clay". A little later on, she has the right amount of legato and warmth for "A presage falls upon thee." That wonderful passage "There was a mortal" is done with appropriate inwardness – I think she does this passage even better here than in the Proms performance. Her account of the celebrated Farewell is lovely. She brings compassion and dignity to this solo and sends the Soul of Gerontius on his way in a most reassuring way.

There is one change to the line up of soloists that took part in the Prom performance and it’s a significant one. In place of Matthew Best, who sang in 2005, Bryn Terfel sings the two bass solos. This is luxury casting indeed. Terfel is a magisterial Priest. His opening phrases are delivered with all the power and sonority that one would expect from this singer. However, I was delighted to note how, as the aria unfolds, he’s attentive to Elgar’s dynamic markings, which are often quiet, and by so doing he makes the Priest’s words properly prayerful. He’s an imposing Angel of The Agony, singing this dramatic solo quite splendidly. One relishes the sheer amplitude of his voice but, once again, one notes how attentive he is to the dynamic markings – and it makes such a difference. Often I’ve found that a soloist is more suited to one of these two solos than the other but on this occasion Terfel is completely successful in both.

At the Proms performance the Hallé Youth Choir, a mixed-voice choir whose members are aged between twelve and nineteen years, sang the crucial semi chorus parts. Their contribution was important then and I’m delighted to find them similarly involved this time. The involvement of these young singers, for whom this recording must have been a tremendous experience, gives this performance an edge over most of its CD rivals. Benjamin Britten scored a significant coup by using the choir of King’s College, Cambridge as the semi chorus when he recorded Gerontius in 1971 and I wonder if Sir Mark Elder had that precedent in mind. The use of young voices, with their completely different timbre, results in a sharp and very telling contrast and I find the effect is really exciting and atmospheric. The writing for the semi chorus is often extremely exposed but the young Hallé singers rise to the challenge superbly and their fresh, youthful voices add an additional and very welcome dimension to the choral sound. I think their involvement is a major success and I applaud it unreservedly.

Their adult colleagues in the main Hallé Choir are also on top form. They’ve obviously been prepared superbly by their chorus master, James Burton. So, every strand is clear in "Be merciful" and they bring real bite and urgency to "Rescue him." In the Demons’ Chorus their singing is virile and has excellent definition. Perhaps they could have snarled a bit more but it’s an exciting account of the chorus. Equally fine is ‘Praise to the Holiest’ and, towards the end, they are clear, controlled and atmospheric at "Lord, Thou hast been our refuge", never an easy passage to bring off.

The orchestral contribution is, if anything, even finer. From the very start of the Prelude to Part I you sense we’re in for something a bit special. The playing glows here and elsewhere. Dynamics are beautifully observed, the rhythms are well articulated and there’s a consistent feeling that the players are right inside the idiom and playing with belief. Two things are worthy of special comment. Firstly, the engineers have contrived to balance the organ beautifully so that whenever it plays it enriches the textures without being unduly prominent. Secondly, the harp part is hugely important and once again, the instrument is balanced perfectly so that time and again one is aware of its importance yet it never draws unwarranted attention to itself.

But for all the splendour of these contributions the whole is knitted into something much greater than the sum of its parts by Sir Mark Elder. Writing of his Prom performance I suggested that one or two of his tempi were a fraction too fleet. I have no such feelings here. I cannot recall a single bar in the whole score when I felt that the pacing wasn’t just right. Elder has demonstrated in several previous Elgar recordings and performances that he is a master interpreter of this composer. This superb interpretation confirms that judgement in spades. His shaping of the Prelude is masterly and that sets the tone for the whole performance. He is scrupulous in his observance of Elgar’s markings and in many ways that’s the key to success in Elgar performance for the composer was copious in the indications he gave in the score and if a conductor trusts Elgar and follows the markings that’s more than half the battle.

The performance has huge sweep and conviction but there are also many small points that show Elder’s meticulous and perceptive attention to detail. One example comes in the Prelude a couple of bars before cue 17 when the orchestra plays a quiet, stabbing chord, with the gong adding a frisson. Elder places and balances that chord to perfection. Move on to the short, hushed Prelude to Part II, for the strings alone. Elder obtains miraculous, luminous textures from his players and in a mere twenty-six bars he establishes an otherworldly atmosphere, just as Elgar intended. Best of all, at cue 3 the dynamic marking is an incredible pppp. Elder achieves precisely that and the effect is superb. Only one other conductor in my experience has matched this, namely Simon Rattle in his 1986 EMI recording, but to be honest, I think even Rattle is put in the shade at this point. These are very small points in themselves but they catch the ear and show the scrupulous attention to detail that has gone into the preparation of this performance.

Elder, however, is anything but a micro-manager. He is magnificent in the big moments. The end of Part I, after the chorus has joined the bass soloist at "Go, in the name of Angels and Archangels", is brought off expertly. Every strand of Elgar’s many-layered tableau is given its proper weight and the whole passage causes the eyes – or my eyes, at any rate – to prickle, as it should. Even better is the long build up to ‘Praise to the Holiest’. This long passage, after the Angel’s solo "There was a mortal" is challenging, but Elder’s direction is superbly assured. Once again, all the various strands - semi chorus, chorus, orchestra and two soloists - are knitted together perfectly. One thing I admired particularly is the way in which Elder paces the several short sections marked Poco più animato with a vernal eagerness and then observes the decelerations, marked by Elgar, to perfection. Here the ladies of the chorus and the younger ladies in the semi chorus sing with a wide-eyed freshness that is completely appropriate to Angelicals. The whole passage is an unqualified success and Elder builds the tension and the atmosphere so that when the choir erupts at "Praise to the Holiest" it is as if great gold doors have been thrown open to reveal blinding light. Elder handles the ensuing chorus masterfully. The last pages, from cue 94 onwards, are tremendously exciting without recourse to excessive speed as Sakari Oramo does on his CBSO recording (see review). The end of the chorus bids fair to lift the roof off the Bridgewater Hall yet Elder’s forces have more to give and manage to observe the crescendo on the last, long chord. It’s a thrilling moment.

One more example of Elder’s perceptive command of the score and of his forces will suffice. In Part II, starting at cue 114, is the remarkable passage where Gerontius sings, "I go before my Judge", followed by the choir’s muffled entreaties, "Be merciful". Elder distils the most incredible atmosphere in these bars. The music has an awestruck quality that I’ve never heard brought out so well. It sounds as if everyone – Paul Groves, the choirs, the orchestra – is on tenterhooks, scarcely daring to articulate the notes. It’s the most remarkable piece of music making imaginable.

So how can I sum up this recording? I think it’s a remarkable achievement and I have been greatly moved by hearing it. Paul Groves and Alice Coote both deliver very fine performances. I feel that both gave a little more in terms of spontaneity during the Proms performance, inspired by the presence of an audience. On the other hand, under studio conditions they achieve some subtle points that were not possible in the huge arena that is the Royal Albert Hall. Bryn Terfel is a superb addition to the cast. The choirs and orchestra are on inspired form and Sir Mark Elder confirms that he is the finest Elgar interpreter now before the public. Under his inspired leadership the white-hot inspiration of Elgar’s visionary score comes alive.

The performance is captured in excellent, atmospheric sound. The recording doesn’t quite have the punch and presence of the Oramo recording but it’s not far short in terms of immediacy. The forces are splendidly and truthfully balanced and the whole project is a great success for the engineers. The notes are by Michael Kennedy and up to that fine writer’s usual immaculate standard.

It has been well worth the wait for this recording. For over forty years Sir John Barbirolli’s great 1964 recording of Gerontius has dominated the catalogue. I’m sure he would rejoice that, in their 150th anniversary year, his beloved Hallé and their distinguished current Music Director have produced a worthy successor and one that offers irrefutable proof that the Elgar tradition of the Hallé is being maintained in the twenty-first century. Let us hope that Sir Mark will go on to give us new and equally fine recordings of Apostles and Kingdom but even if that doesn’t happen they have done Elgar proud with this distinguished recording which I have found to be a very moving experience.

-- John Quinn, MusicWeb International

Elgar: The Apostles / Imbrailo, Groves, Coote, Elder, Halle Orchestra

Performed beautifully. Everyone is on quite spectacular form.

The 2011/12 season was a memorable one for the Hallé and its Music Director Sir Mark Elder who was celebrating his twelfth season with the Manchester based orchestra. What was for me a rather uninspiring Beethoven cycle was overshadowed by three unforgettable performances that will serve to increase the Hallé Orchestra’s burgeoning international reputation. In November 2011 the Bridgewater audience were treated to John Adams’s Harmonium for chorus and orchestra (1980/81) a setting of poems by John Donne and Emily Dickinson. Next, in collaboration with the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, in April 2012 Sir Mark took the Hallé into the pit at the Lowry Theatre, Salford Quays for a spellbinding production of Bernstein’s feel-good musical Wonderful Town starring actress/singer Connie Fisher. Back home at the Bridgwater Hall on 5 May 2012 we were treated to this inspirational performance of Elgar’s The Apostles. Dedicated ‘ To the Greater Glory of God’ The Apostles is a large-scale two part oratorio for soloists, choir and orchestra written in the English choral tradition. Elgar selected his own texts from the Bible and the Apocrypha. Elgar himself introduced the oratorio at the Birmingham Triennial Festival in 1903.

I was present that Saturday May evening reporting on The Apostles for Seen and Heard International and this review is essentially based on that report. Together with a number of friends we had travelled down to witness a performance that will live long in the memory. Thankfully the Hallé’s performance under Sir Mark was recorded together with a rehearsal for patching purposes. As expected the performance was taken extremely seriously and far more hours than normally allocated for rehearsal were clocked up.

Prior to the start there was an uplifting feeling of keen anticipation in the packed hall. It’s a shame that the listener not present on the night cannot also share that sense of expectancy. Eschewing histrionics, one hardly noticed Sir Mark on the podium, just getting on with the job of directing this substantial work. This was a highly assured account all the more impressive given the task of bringing the massed forces together in a coherent way. I particularly admired the unerring control of the massive dynamic extremes with tempi that felt judicious. Potency and beautifully incisive playing demonstrated the orchestra’s ascendant prowess.

In radiant voice the choirs made a significant contribution to the evening’s success. This was matched in passionate commitment by the sextet of well chosen soloists. Standing out magnificently was Jacques Imbrailo as Jesus. He solidly projected his richly mellow and expressive timbre with immense purpose. A fine choice as the First Narrator/John was Paul Groves who was notable for his steady bright and clear diction. Brindley Sherratt’s Judas was well powered, polished and authoritative. Although acceptable bass-baritone David Kempster in the role of Peter at times became rather swamped by the choir and orchestra and would have benefited from a greater amplitude and clearer diction. Rebecca Evans as the Angel Gabriel/Virgin Mary was bright with a moderately warm sound and sang with affecting piety. Evans’ vibrato was noticeable but never intruded. Mezzo-soprano Alice Coote as Mary Magdalene/Second Narrator has a substantial amount of text to sing. She was in glorious, reverential voice, well projected throughout.

Right from the orchestral Prelude to the scene The Calling of the Apostles the choir intoning the words from St. Luke’s Gospel To preach the acceptable year of the Lord sent a shiver down the spine. We were left in no doubt but that we had embarked on a visionary journey. The programme notes for the concert asserted that a genuine shofar player had been found. This caused much discussion amongst many audience members and subsequently on internet message boards. If people expected a traditional Hebrew Ram’s horn instrument that wasn’t what soloist Bob Farley played. From my seat it looked like a crossbreed of some sort of long straight brass trumpet that I would guess was around 6ft long becoming slightly angled just before the start of the bell. Nevertheless the playing, by the soloist positioned at the side of the hall, made a splendid impact both sonically and theatrically. The shofar can be heard to memorable effect at the start of CD 1 track 3.

At the beginning of Part 2 the solemn orchestral Introduction to the scene of The Betrayal of Christ was remarkable, with the doom-laden brass being lightened by the strings and winds then darkening again with all the drama of a Puccini opera. Depicting the crucifixion, the disturbing Golgotha section featured weighty orchestral textures especially the shadowy-toned brass and percussion. The electrifying final section The Ascension of Christ to heaven in his resurrected body required all the forces uniting in a colossal Alleluia. This was one of the most moving things I’ve experienced in classical music.

Released on the Hallé’s own label I found the sound quality of the Hallé/Elder disc highly satisfying. To the infuriation of many audience members an errant clapper virtually instantaneously at the end of both halves ruined the special moments of contemplation. Thankfully I can report that the patching session has successfully removed the unwanted racket. Michael Kennedy’s booklet notes are as authoritative as I would expect from this Elgar scholar. It’s good to see that a full libretto is included in the booklet. Some incorrect numbering against the part two text is the only glitch I found with this issue.

The rival recordings of The Apostles include the digitally re-mastered analogue 1973/74 account from the Kingsway Hall, London under the baton of Sir Adrian Boult with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir on EMI. Then there’s the 1990 digital recording from St. Jude on the Hill, Hampstead, London by the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus under Richard Hickox on Chandos. Both are very fine performances. Of the two I favour the Boult/EMI for its splendid singing and sense of reverential awe. On the down-side Boult’s singers may sound dated to some listeners and the LPO’s distinctive bottom-heavy sound can be off-putting. On balance the recording of The Apostles that I will reach out for the most will be this new Hallé release. It’s performed beautifully throughout and achieves an otherwise elusive spirituality. Everyone is on quite spectacular form. If proof were needed of the importance of The Apostles then this release is the evidence.

-- Michael Cookson, MusicWeb International

Elgar: Sea Pictures, Polonia & Pomp and Circumstances Marches / Halle

Premiered in 1899, shortly after the triumph of the Enigma Variations in London the previous month, Sea Pictures became an immediate hit (with two of the songs being performed with piano accompaniment for Queen Victoria at Balmoral two weeks after the premiere). The cycle of five songs for which Elgar selected a variety of poems from his wide knowledge of literature, features a range of masterly orchestral textures and stunning vocal settings.

The featured soloist is world renowned mezzo soprano Alice Coote, regarded as one of the leading artists of our day, equally famed on the great operatic stages as in concert and recital.

Polonia has long been overlooked but this recording will re-establish this highly engaging tone poem which quotes Polish tunes and Chopin, written as a tribute to Poland’s contribution to the Allied cause in the First World War, in a brilliantly orchestrated score.

Not all of the five original Pomp and Circumstance Marches are as universally well known as No.1 and No.4 and, although constructed on the same structural pattern, they display an extraordinary variety of character. These orchestral showcases are a perfect vehicle with which to display the technical and artistic skill of the Hallé under Elder.

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}