Jan Dismas Zelenka

40 products

-

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Thorofon

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

ThorofonZelenka: Missa Sanctissimae Trinitatis / Wehnert, Et Al

Classical Music

$24.99May 01, 1995 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

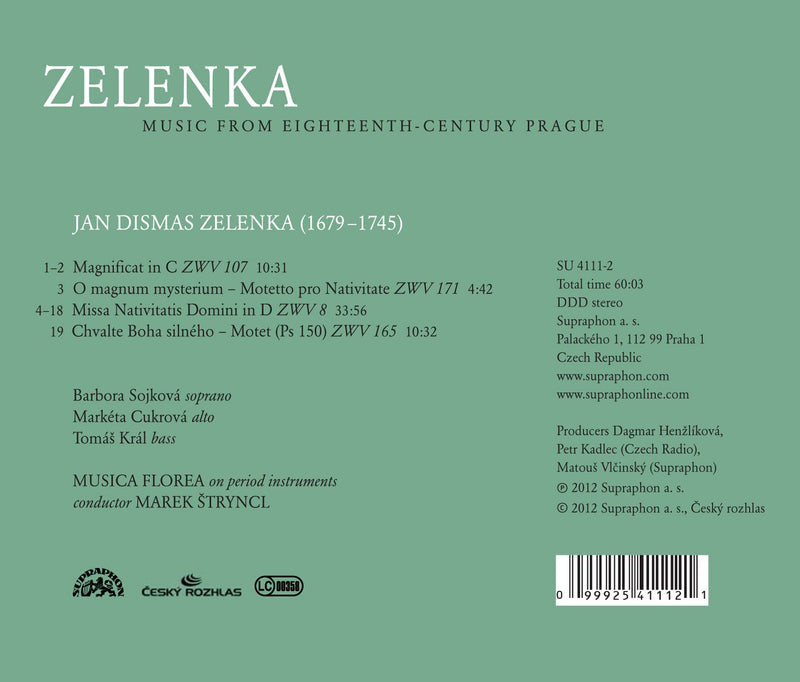

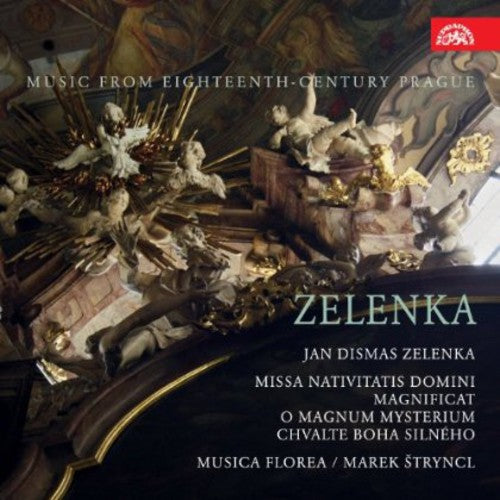

On SaleSupraphon

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

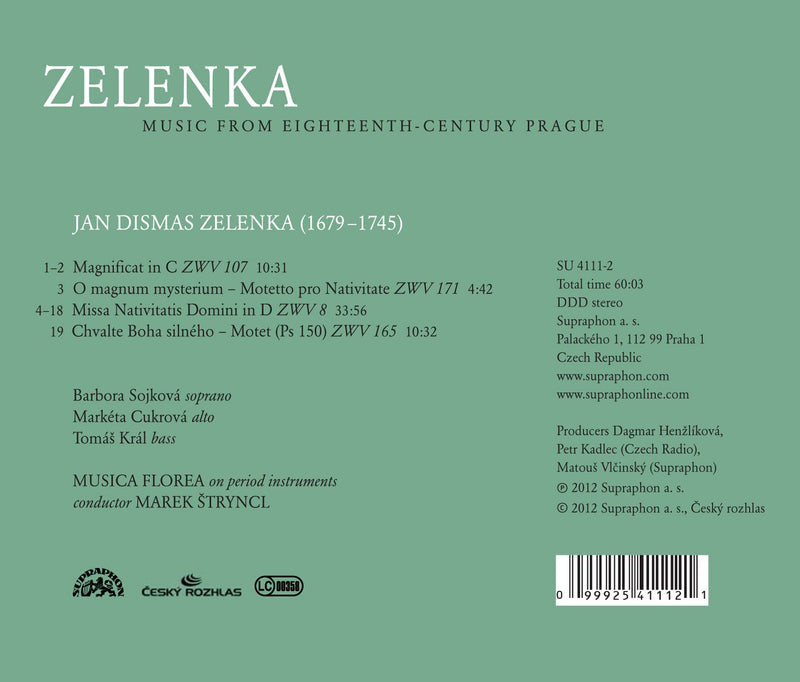

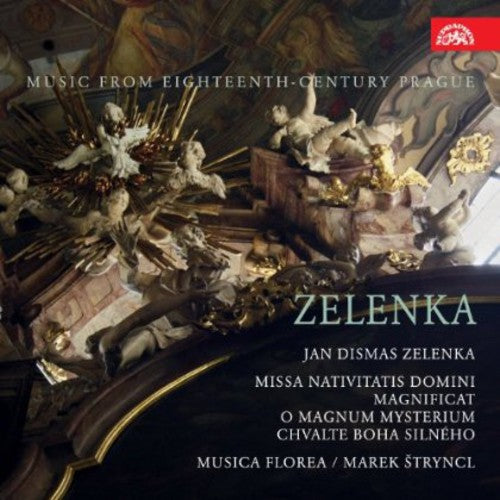

On SaleSupraphonZelenka: Missa Nativitatis Domini; Magnificat; O Magnum Mysterium / Stryncl, Musica Florea

At times startling and innovative sacred choral works by the most important Bohemian composer of the Baroque era, Jan Dismas Zelenka. Digitally...

January 29, 2013$31.99$23.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

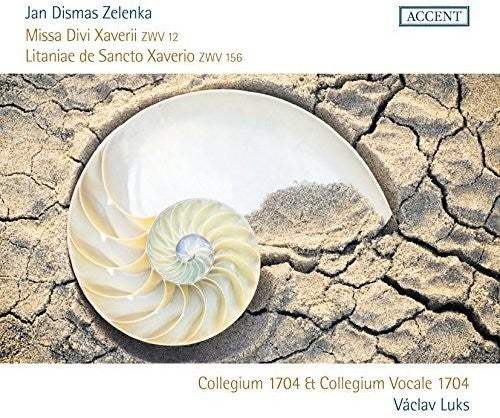

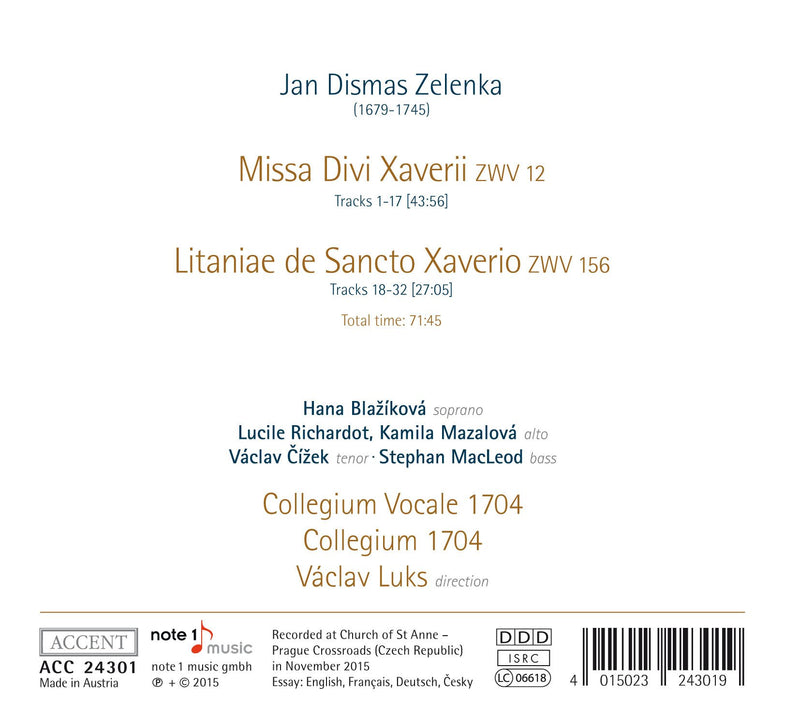

Accent

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

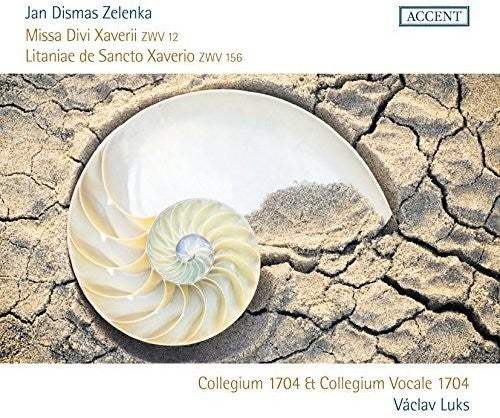

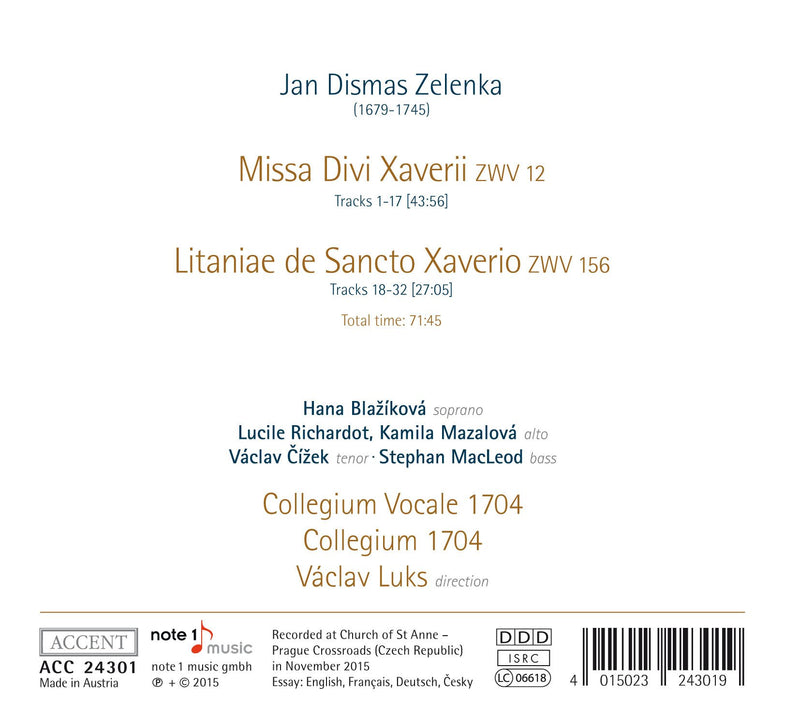

AccentZelenka: Missa Divi Xaverii & Litaniae de Sancto Xaverio / Luks, Collegium 1704

$20.99March 25, 2016 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleSupraphon

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleSupraphonZelenka: Melodrama De Sancto Wenceslad / Stryncl, Musica Florea

Here's a case where the music so completely and satisfyingly transcends the texts, that we can thoroughly enjoy the proceedings without really...

January 29, 2013$47.99$35.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleSupraphon

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

On SaleSupraphonZelenka: Lamentationes Jeremia Propheta

The Old Testament Book of Lamentations has been subjected to a number of settings since the Middle Ages; that of Jan Dismas...

October 14, 2014$31.99$23.99 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Passacaille

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

PassacailleZelenka: De Profundis, Etc / Paul Dombrecht, Il Fondamento

ZELENKA Requiem in c, ZWV 48. Miserere in c, ZWV 57. De profundis in d, ZWV 57 • Paul Dombrecht, cond; Monika...

$21.99October 13, 2009 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Passacaille

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

PassacaillePrague 1723 - Zelenka / Paul Dombrecht, Il Fondamento

ZELENKA Requiem in c, ZWV 48. Miserere in c, ZWV 57. De profundis in d, ZWV 57 • Paul Dombrecht, cond; Monika...

$21.99October 13, 2009 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Linn Records

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Linn RecordsJan Dismas Zelenka: Sonatas

ZELENKA Sonatas, ZWV 181/3, 5, 6. Symphonie à 8 Concertanti: Andante • Monica Huggett (vn); Ensemble Marsyas • LINN CKD 415 (SACD:...

$21.99October 30, 2012 -

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

Accent

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

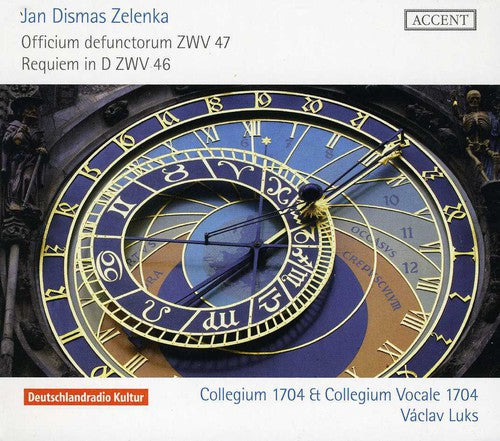

AccentJan Dismas Zelenka: Officium Defunctorum, Zwv 47; Requiem In D, Zwv 46

ZelenkaÂ?Â?Â?Â? Collegium 1704 & Collegium Volcale 1704/Vaclav Luks Music for the Funeral Rites of Augustus the Strong

$32.99February 01, 2011 -

-

-

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

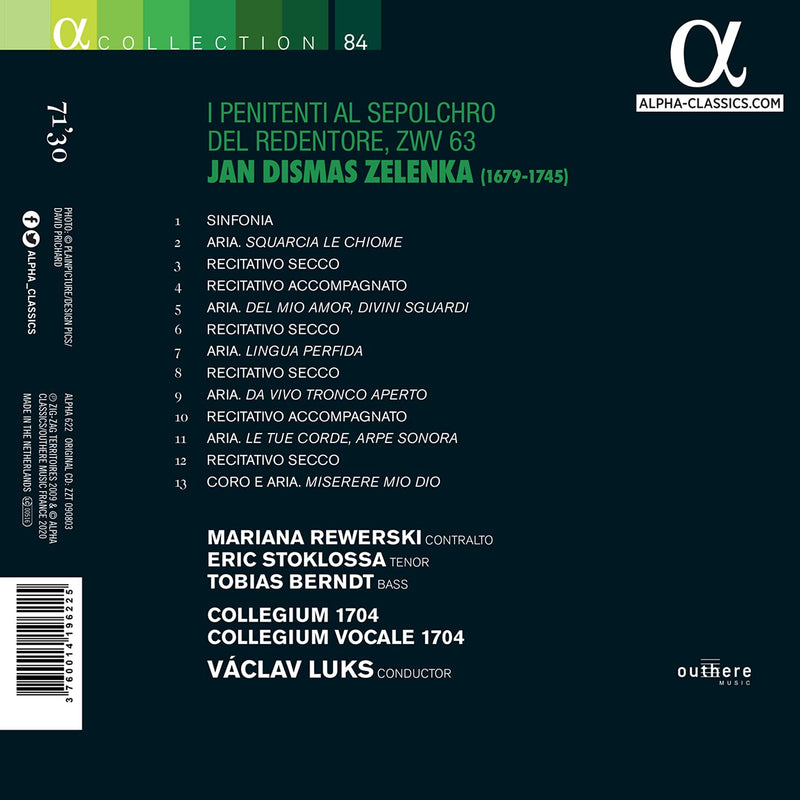

Alpha

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

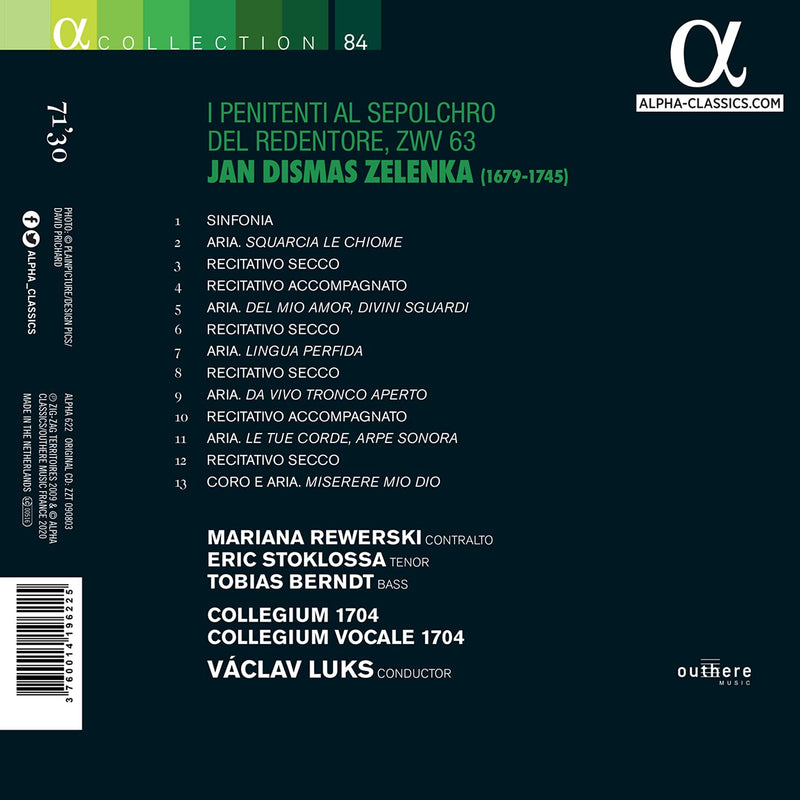

AlphaZelenka: I Penitenti al Sepolcro / Luks, Collegium 1704

The Prague-based ensemble Collegium 1704 and its founder Vaclav Luks here perform an oratorio by the Czech composer Jan Dismas Zelenka. This...

$11.99June 25, 2021

Zelenka: Missa Sanctissimae Trinitatis / Wehnert, Et Al

Zelenka: Missa Nativitatis Domini; Magnificat; O Magnum Mysterium / Stryncl, Musica Florea

At times startling and innovative sacred choral works by the most important Bohemian composer of the Baroque era, Jan Dismas Zelenka. Digitally recorded on 7 and 8 December, 2011 in the Church of St. Simon and St. Jude in Prague. Album includes booklet notes in English, French, German and Czech with lyrics sung in Latin and translated in four languages.

Zelenka: Missa Divi Xaverii & Litaniae de Sancto Xaverio / Luks, Collegium 1704

Zelenka: Melodrama De Sancto Wenceslad / Stryncl, Musica Florea

The opening Sinfonia is a brilliant enough piece all on its own, but the chorus that immediately follows takes us to yet another level of excitement, setting a sumptuously decorated stage for what is to come. Although there's a substantial amount of music here, no one section stays too long, and the arias show care for musical beauty well beyond anything suggested by the texts. And there's nothing pale or simple in the writing either, whether for instruments or voices: much of it, especially the vocal solos, requires performers of considerable accomplishment, even virtuosity. The opening chorus is quite a tour de force, and in this performance we're treated to the lovely sound and impeccable technique of the boys' and men's voices of the Czech choir Boni Pueri. That this is a Czech production mirrors its original performance in Prague's Jesuit Clementinum, which not only involved native Czech singers and actors, but also was conducted by the Czech-born Zelenka. The orchestral writing, which includes such ceremonial staples as trumpets and timpani, used to great effect, is bright-spirited and masterfully constructed to hold our interest and maintain dramatic momentum. The soloists are generally very good and there's some really terrific interaction in duets and in dialogs with the chorus. The sound is full-bodied and sufficiently detailed to give immediate presence to all the performers while preserving appropriate balances. Anyone who enjoys large-scale Baroque choral/orchestral music will love this unusual and musically engaging work--another gem in the crown of a composer that's finally getting just recognition.

--David Vernier, ClassicsToday.com

Reviewing original release, Supraphon 3520

Zelenka: Lamentationes Jeremia Propheta

Zelenka: De Profundis, Etc / Paul Dombrecht, Il Fondamento

ZELENKA Overture in F. Hipochondrie in A. Concerto in G. Simphonia in a • Paul Dombrecht, cond; Il Fondamento (period instruments) • PASSACAILLE 9524 (66:22)

Despite being elevated by some to near-cult status, Jan Dismas Zelenka remains an enigmatic figure. Little more than the bare outlines are known of a career marked by the ultimate disappointment of being passed over for the post of Kapellmeister in Dresden in favor of Johann Hasse, 20 years his junior. Of his personality we know next to nothing, leaving us puzzled by a man whose music can be variously termed idiosyncratic, highly individual, or just plain eccentric according to taste. Was Zelenka therefore a great original genius of the High Baroque, plowing his own lonely furrow, or simply a composer of bizarre curiosities? Paul Dombrecht has recently been involved with a selection of both the sacred and secular works of Zelenka, so he seemed a good man to approach for an opinion. "He is certainly a very individual composer," Dombrecht told me, "and difficult to categorize or place within any particular school. In Dresden he worked alongside people like Heinichen, Pisendel, and later Hasse, and he has a much more personal style than any of them. It could be that for this reason he was not really successful." "Yes, I've often wondered to what extent his unusual style played a part in the decision to appoint Hasse Kapellmeister in Dresden after the death of Heinichen. After all, he had been for some years." "It could be that, or it might have been his personality. We just don't know."

No better example of the originality of Zelenka's style could be found than the Miserere in C Minor recorded by Dombrecht, a work that, as he points out, consists of an amalgam of several styles. "In the Miserere Zelenka is mixing styles in quite strange and sudden ways. You have this very dramatic opening, then a fugal section in which he gets through a long section of text very quickly, often overlapping it. The next section [the first part of the Gloria, a florid soprano solo] is again in a completely different style. It could be taken from an opera." Indeed it could, the style that springs to mind being that of Hasse, the man who blocked Zelenka's progress in Dresden. That fugal section strikes me, like some of Zelenka's other contrapuntal sections, to be the kind of passage that arouses doubts about Zelenka, writing in which the odd melodic angularity seems awkward. I asked Dombrecht if he agreed. "Yes, that's one of the reasons why he is not always appreciated. It's the same with the trio sonatas—they look very complex, and there are those who say the music is not well constructed." Yet there are, of course, others to whom the composer's compelling originality overrides such doubts, and it is always worth recalling that C. P. E. Bach claimed that his father held Zelenka's music in high esteem. For evidence that the Bohemian was a highly accomplished contrapuntist, one need turn no further than the "Tu suscipe" section of the C-Minor Requiem, an a cappella setting in the stile antico. As Dombrecht pointed out, such accomplishment doubtless dates from the period Zelenka spent in Vienna as a pupil of the great contrapuntist J. J. Fux, this, remarkably, when the former was already in his mid-thirties. "For me," Dombrecht concluded, "it is the obvious sincerity of the manner in which Zelenka uses such devices that makes him so interesting."

The seven works recorded by Dombrecht provide a representative cross-section of Zelenka's sacred and orchestral works spanning a period from 1723 to 1738. The earliest are the four orchestral works, all of which are dated 1723, the year in which Zelenka traveled to Prague with a group of Dresden musicians for the coronation of Charles VI. In addition to ceremonial vocal works by Zelenka himself and Fux, it is known that the former composed six orchestral works that no doubt played their part in the festivities. The four chosen by Dombrecht graphically illustrate not only Zelenka's originality but the diversity of style to be found throughout the composer's works. The Overture in F is cast in suite form, with an opening French overture full of grandeur, the mixture of dotted chordal writing interposed with a melodic motif that characteristically refuses to go in quite the expected direction. The Aria that follows is equally notable, its graceful surface disconcertingly disrupted by minor inflections and surprising harmonic progressions. Here, as in some of the other dance movements, there are moments that suggest the composer has taken a distorting mirror to a world of the courtly and elegant.

The G-Major Concerto inhabits another world, that of the concerto con molti stromenti, imported from Venice via Vivaldi, and enthusiastically adopted by Zelenka's Dresden colleagues, Heinichen and Pisendel. Yet if the strong opening unison reminds us of the Venetian master, the folklike melody that follows is archetypal Zelenka, as is the plaintive oboe and bassoon dialog that forms the heart of the succeeding Largo cantabile. The oddly named Hipocondrie is a single-movement work, a broad, melodic Lentement framing a central Allegro much concerned with antiphonal imitative effects and contrasts of instrumental color. The considerably truncated return of the slow opening brings yet another Zelenka surprise, the unexpected turn to the minor, with stabbing bass chords bringing the work to a somber close. In some ways the Simphonie is the most conventional work here, but there is nothing ordinary about the burst of exuberant abandon with which the composer launches into the opening Allegro. In this, arguably the most appealing of these orchestral works, the succeeding movements introduce much felicitous concertante writing, often for pairs of instruments. Especially memorable is the Andante's conversation between violin and oboe conducted over a bubbling bassoon figuration. Il Fondamento's performances of all these works are impeccable, the many solo concertino passage played with stylish confidence and unfailing technical expertise, while Dombrecht captures the spirit of Zelenka impressively, allowing full rein to the phrasing of his often oddly shaped melodies, and directing the more boisterous movements with energetic verve.

The disc of sacred music is equally outstanding, the instrumental forces of II Fondamento here complemented by a small (16 voices) but accomplished, eagerly responsive chorus, and a fine lineup of soloists among whom the vastly experienced and ever-dependable Peter Kooij particularly stands out. The earliest of these works is the De profundis, composed as a commemorative work around 1724. The work reflects not only the solemnity of the occasion but also the opening words of the Psalm (130): "Out of the deep. . . ." A dark-hued orchestral introduction leads to a setting of the opening lines for three solo basses, music of painful beauty set over an inexorable walking bass. The gravity of the music is further underlined by the three trombones that punctuate the chorus's succeeding "Si iniquitates," while the central section is given to the tenor and alto soloists, the expansive melismatic lines counterpoised by an obbligato oboe. After Zelenka was appointed court chapel conductor in 1732 his output of church compositions increased, one of the first results being the C-Minor Requiem, believed to date from that year. This too was composed for a commemoration, an annual ritual held in Dresden in memory of the death of Emperor Joseph I. Rather surprisingly for a work that had to be fitted into a complete framework lasting no more than an hour, Zelenka set the whole of the Requiem text. With the exception of the "Liber scriptus" (a lovely setting for solo tenor and bass) and the Benedictus, each of the 22 sections is very short, even further concision being achieved by telescoping the text in the long Sequence. Despite some striking moments, the effect of a succession of movements lasting an average of barely two minutes is less than totally satisfactory. But as ever with Zelenka there is some striking orchestration, not least for the chalumeau, which appears in several sections of the Sequence.

Composed in 1738, the Miserere in C Minor is the latest and in some ways most impressive of these works, despite the caveat mentioned in the introduction to this review. The pounding bass introduction over which dissonance is piled on dissonance exerts an extraordinarily powerful impression on the listener, the kind of writing that immediately grabs the attention and makes one think: Yes, this is the work of a true original who has something startling and dramatic to say. While they cannot solve the Zelenka enigma, hearing these two discs in conjunction does provide an unusual opportunity to move just that little closer to this hugely talented, mysterious figure. Sadly, the presentation fails match the outstanding quality of the performances and engineering, the note accompanying the disc of sacred works being inadequate and confused, while both sets of notes have been poorly proofread.

Brian Robins, Fanfare [9/2000]

--------

Bach’s Bohemian contemporary Zelenka worked for most of his life in Dresden, where he played the double bass in the excellent and renowned court orchestra. He was a composer with a rewarding streak of originality, sometimes quirky but often colourful and expressively exciting. That much immediately becomes apparent in the opening phrases of his fine C minor Miserere whose scourging inflections with their anguished suspensions vividly complement the spirit of the psalm text. It’s a piece which, in some respects, defies neat classification, containing sections allied to the early classical style with others that are of a stricter discipline, more austere and which remind us that among his most important mentors were Fux in Vienna and Lotti in Venice. The remaining two works are hardly less interesting. One of them is an effective setting of the psalm De profundis which, like the Miserere, comprises mainly choral sections and contains some arresting passages for three trombones. The other is, at least in respect of length, the main feature of the programme. It’s a Requiem in C minor which has surprises in store at almost every turn. New and older styles jostle together throughout, almost always informed by Zelenka’s distinctive craftsmanship and his highly developed sense of orchestral colour. The lyrical ‘Liber scriptus’ with engaging passages for oboes and chalumeau is such an instance, while the concluding chorus of the Kyrie offers the listener a fine example of the composer’s contrapuntal art. Here are rewarding performances of late Baroque repertoire which is anything but mainstream.

Performance: 5 (out of 5); Sound: 5 (out of 5)

-- Nicholas Anderson, BBC Music Magazine

Prague 1723 - Zelenka / Paul Dombrecht, Il Fondamento

ZELENKA Overture in F. Hipochondrie in A. Concerto in G. Simphonia in a • Paul Dombrecht, cond; Il Fondamento (period instruments) • PASSACAILLE 9524 (66:22)

Despite being elevated by some to near-cult status, Jan Dismas Zelenka remains an enigmatic figure. Little more than the bare outlines are known of a career marked by the ultimate disappointment of being passed over for the post of Kapellmeister in Dresden in favor of Johann Hasse, 20 years his junior. Of his personality we know next to nothing, leaving us puzzled by a man whose music can be variously termed idiosyncratic, highly individual, or just plain eccentric according to taste. Was Zelenka therefore a great original genius of the High Baroque, plowing his own lonely furrow, or simply a composer of bizarre curiosities? Paul Dombrecht has recently been involved with a selection of both the sacred and secular works of Zelenka, so he seemed a good man to approach for an opinion. "He is certainly a very individual composer," Dombrecht told me, "and difficult to categorize or place within any particular school. In Dresden he worked alongside people like Heinichen, Pisendel, and later Hasse, and he has a much more personal style than any of them. It could be that for this reason he was not really successful." "Yes, I've often wondered to what extent his unusual style played a part in the decision to appoint Hasse Kapellmeister in Dresden after the death of Heinichen. After all, he had been for some years." "It could be that, or it might have been his personality. We just don't know."

No better example of the originality of Zelenka's style could be found than the Miserere in C Minor recorded by Dombrecht, a work that, as he points out, consists of an amalgam of several styles. "In the Miserere Zelenka is mixing styles in quite strange and sudden ways. You have this very dramatic opening, then a fugal section in which he gets through a long section of text very quickly, often overlapping it. The next section [the first part of the Gloria, a florid soprano solo] is again in a completely different style. It could be taken from an opera." Indeed it could, the style that springs to mind being that of Hasse, the man who blocked Zelenka's progress in Dresden. That fugal section strikes me, like some of Zelenka's other contrapuntal sections, to be the kind of passage that arouses doubts about Zelenka, writing in which the odd melodic angularity seems awkward. I asked Dombrecht if he agreed. "Yes, that's one of the reasons why he is not always appreciated. It's the same with the trio sonatas—they look very complex, and there are those who say the music is not well constructed." Yet there are, of course, others to whom the composer's compelling originality overrides such doubts, and it is always worth recalling that C. P. E. Bach claimed that his father held Zelenka's music in high esteem. For evidence that the Bohemian was a highly accomplished contrapuntist, one need turn no further than the "Tu suscipe" section of the C-Minor Requiem, an a cappella setting in the stile antico. As Dombrecht pointed out, such accomplishment doubtless dates from the period Zelenka spent in Vienna as a pupil of the great contrapuntist J. J. Fux, this, remarkably, when the former was already in his mid-thirties. "For me," Dombrecht concluded, "it is the obvious sincerity of the manner in which Zelenka uses such devices that makes him so interesting."

The seven works recorded by Dombrecht provide a representative cross-section of Zelenka's sacred and orchestral works spanning a period from 1723 to 1738. The earliest are the four orchestral works, all of which are dated 1723, the year in which Zelenka traveled to Prague with a group of Dresden musicians for the coronation of Charles VI. In addition to ceremonial vocal works by Zelenka himself and Fux, it is known that the former composed six orchestral works that no doubt played their part in the festivities. The four chosen by Dombrecht graphically illustrate not only Zelenka's originality but the diversity of style to be found throughout the composer's works. The Overture in F is cast in suite form, with an opening French overture full of grandeur, the mixture of dotted chordal writing interposed with a melodic motif that characteristically refuses to go in quite the expected direction. The Aria that follows is equally notable, its graceful surface disconcertingly disrupted by minor inflections and surprising harmonic progressions. Here, as in some of the other dance movements, there are moments that suggest the composer has taken a distorting mirror to a world of the courtly and elegant.

The G-Major Concerto inhabits another world, that of the concerto con molti stromenti, imported from Venice via Vivaldi, and enthusiastically adopted by Zelenka's Dresden colleagues, Heinichen and Pisendel. Yet if the strong opening unison reminds us of the Venetian master, the folklike melody that follows is archetypal Zelenka, as is the plaintive oboe and bassoon dialog that forms the heart of the succeeding Largo cantabile. The oddly named Hipocondrie is a single-movement work, a broad, melodic Lentement framing a central Allegro much concerned with antiphonal imitative effects and contrasts of instrumental color. The considerably truncated return of the slow opening brings yet another Zelenka surprise, the unexpected turn to the minor, with stabbing bass chords bringing the work to a somber close. In some ways the Simphonie is the most conventional work here, but there is nothing ordinary about the burst of exuberant abandon with which the composer launches into the opening Allegro. In this, arguably the most appealing of these orchestral works, the succeeding movements introduce much felicitous concertante writing, often for pairs of instruments. Especially memorable is the Andante's conversation between violin and oboe conducted over a bubbling bassoon figuration. Il Fondamento's performances of all these works are impeccable, the many solo concertino passage played with stylish confidence and unfailing technical expertise, while Dombrecht captures the spirit of Zelenka impressively, allowing full rein to the phrasing of his often oddly shaped melodies, and directing the more boisterous movements with energetic verve.

The disc of sacred music is equally outstanding, the instrumental forces of II Fondamento here complemented by a small (16 voices) but accomplished, eagerly responsive chorus, and a fine lineup of soloists among whom the vastly experienced and ever-dependable Peter Kooij particularly stands out. The earliest of these works is the De profundis, composed as a commemorative work around 1724. The work reflects not only the solemnity of the occasion but also the opening words of the Psalm (130): "Out of the deep. . . ." A dark-hued orchestral introduction leads to a setting of the opening lines for three solo basses, music of painful beauty set over an inexorable walking bass. The gravity of the music is further underlined by the three trombones that punctuate the chorus's succeeding "Si iniquitates," while the central section is given to the tenor and alto soloists, the expansive melismatic lines counterpoised by an obbligato oboe. After Zelenka was appointed court chapel conductor in 1732 his output of church compositions increased, one of the first results being the C-Minor Requiem, believed to date from that year. This too was composed for a commemoration, an annual ritual held in Dresden in memory of the death of Emperor Joseph I. Rather surprisingly for a work that had to be fitted into a complete framework lasting no more than an hour, Zelenka set the whole of the Requiem text. With the exception of the "Liber scriptus" (a lovely setting for solo tenor and bass) and the Benedictus, each of the 22 sections is very short, even further concision being achieved by telescoping the text in the long Sequence. Despite some striking moments, the effect of a succession of movements lasting an average of barely two minutes is less than totally satisfactory. But as ever with Zelenka there is some striking orchestration, not least for the chalumeau, which appears in several sections of the Sequence.

Composed in 1738, the Miserere in C Minor is the latest and in some ways most impressive of these works, despite the caveat mentioned in the introduction to this review. The pounding bass introduction over which dissonance is piled on dissonance exerts an extraordinarily powerful impression on the listener, the kind of writing that immediately grabs the attention and makes one think: Yes, this is the work of a true original who has something startling and dramatic to say. While they cannot solve the Zelenka enigma, hearing these two discs in conjunction does provide an unusual opportunity to move just that little closer to this hugely talented, mysterious figure. Sadly, the presentation fails match the outstanding quality of the performances and engineering, the note accompanying the disc of sacred works being inadequate and confused, while both sets of notes have been poorly proofread.

Brian Robins, Fanfare [9/2000]

Jan Dismas Zelenka: Sonatas

ZELENKA Sonatas, ZWV 181/3, 5, 6. Symphonie à 8 Concertanti: Andante • Monica Huggett (vn); Ensemble Marsyas • LINN CKD 415 (SACD: 49:43)

It was the pioneering Archiv recordings from 1978 of Jan Dismas Zelenka’s trio sonatas and orchestral works, with an instrumental ensemble including the celebrated oboist Heinz Holliger, that put the composer’s name and music back into circulation after two centuries of obscurity. Since then the sonatas have become far and away Zelenka’s most recorded compositions, continuing to attract admirers for their inventive quirkiness. As three other Fanfare critics—John Bauman, Michael Carter, and Brian Robins—have ably discussed the music in extensive detail in their reviews of previous sets, I will refer readers to their discussions and focus upon a comparison of complete recordings in the original instrumentation for two oboes (with one replaced by a violin in the Third Sonata), bassoon, and continuo. (There have also been partial sets and recordings of arrangements made for string ensembles.)

The aforementioned Archiv recording with Holliger either was not reviewed in these pages, or else any such review has not yet made its way into the online Archive; it is available as both a reissue in its original form from ArkivMusic.com and in a budget version from Brilliant Classics. Holliger made a second recording, for ECM in 1999, with some of the same instrumentalists as before; Robins praised that set in 23: 2 as well played but stated it was not to his taste, as he “simply cannot accept the thin, pinched sound of a pair of modern oboes in this music.” By contrast, Carter placed it in the Classical Hall of Fame in 26:4. In successive reviews in 17:5, 19:2, 19:4, and 19:5, Bauman praised both an MDG set with the Northwest German Chamber Soloists and a Claves set with members of the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, ranking them above the older Archiv set and dismissing a Berlin Classics set with oboist Burkhard Glaetzner with the comment that “these fine German musicians come as close to making Zelenka as dull as seems likely.” However, he endorsed as first choices an Accent set with a group of Belgian performers and two discs by Astrée with the Ensemble Zefiro as being “far and away the most exciting and imaginative we have had in the last several decades.” Robins also endorsed the Ensemble Zefiro as a first choice in his review of the ECM set. Contrary to Baumann, Carter had high praise for the Berlin Classics set in 30:1, ranking it as being virtually equal to the ECM release. There is one other set in print that has not been reviewed here, a Matous release from 1993 with a group of Czech musicians.

For my part, I do not find myself in complete agreement with any of the above critics. For fans of Holliger, the ECM set is clearly superior to the old Archiv version: I agree with Robins and Carter on its merits, and unlike the former I do not object to hearing this music played on modern instruments, even though I do prefer period instruments for it. Unfortunately the Astrée discs and MDG set are both out of print. The few used copies of the former available through Amazon.com are advertised at obscene prices; those for the latter are more reasonable. Movements from some of the sonatas as played by Ensemble Zefiro are posted on YouTube; while handsomely played, I’m not as enthusiastic for them as either Bauman or Robins. The MDG set is solid, but I would prefer both the ECM and Astrée versions to it. I cannot concur with Bauman’s enthusiasm for the Accent set; it is a rare instance of a period ensemble engaging in stodgy, foursquare playing, and has an unnaturally reverberant recording acoustic. I agree with Bauman and disagree with Carter regarding the Berlin Classics recordings; they are indeed rather dull affairs, as is the Claves set. However, my endorsement would go to the hitherto neglected Matous release, which features elegant, vibrant, and heartfelt playing in a very attractive recorded acoustic. The fly in the ointment there is that it is the most expensive alternative, costing over $40.00, whereas the ECM set can be had far more cheaply.

How does the present release compare with all of the preceding alternatives? Quite favorably; Ensemble Marsyas is a newly formed Scottish ensemble of baroque musicians, and this release marks an impressive recording debut. The performances are on period instruments, with the continuo parts variously played on violone, theorbo, harpsichord, and/or organ. Everyone blends well, and the tone colors are striking; I am particularly taken with bassoonist Peter Whelan, the ensemble’s founder, who offers by far the most pungent rendition of his part in any recording made of this music. Violinist Monica Huggett is, as one would expect, a most accomplished soloist in the Third Sonata, and the two oboists are quite agile. The booklet provides detailed and informative notes and several color photos. While I’m not convinced that SACD technology adds anything significant to a chamber ensemble beyond standard digital recording, the recorded sound is quite pleasing. My one point of hesitation is that I cannot find any indication as to whether a sequel disc is planned for the other three sonatas. If and when that appears, this would become the new set of choice. Until then, for a complete cycle go with ECM or Mantous, but do buy this now if you love these pieces and have the cash to spare; recommended.

FANFARE: James A. Altena

Jan Dismas Zelenka: Officium Defunctorum, Zwv 47; Requiem In D, Zwv 46

ZelenkaÂ?Â?Â?Â? Collegium 1704 & Collegium Volcale 1704/Vaclav Luks Music for the Funeral Rites of Augustus the Strong

Zelenka: I Penitenti al Sepolcro / Luks, Collegium 1704

The Prague-based ensemble Collegium 1704 and its founder Vaclav Luks here perform an oratorio by the Czech composer Jan Dismas Zelenka. This edifying work, typical of the oratorios produced during the Counter-Reformation, presents the faithful with an imaginary meeting of Mary Magdalene, King David and St Peter at the Tomb of Christ. After the success of the Red, Yellow, Blue, Pink and White collections (a total of sixty reissues) which gave a new lease of life to the pearls of the Baroque catalogues from our house labels, here are fourteen new titles which offer a chance to discover other treasures, whether Baroque or dating from an earlier or later era. Like the most recent series, this sixth instalment opens out onto the Classical repertory (Mozart by Ensemble 415 and Chiara Banchini) and the Renaissance (Févin by Doulce Mémoire and Denis Raisin Dadre); recordings that are an integral part of Alpha’s identity and history. Fourteen reissues performed by the leading musicians in the field, most of which received one or more awards on their original release. Proper booklets accompany the discs, with notes in three languages (French, English, German). Photographers from all over the world have been selected to illustrate the covers, this time with the guiding thread of the color green, a symbol of nature, fertility... and hope!

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}

{# optional: put hover video/second image here positioned absolute; inset:0 #}